Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - CXVIII

The Phantom Charge of ‘Clericalism’

It is a matter of historical record that sloganeering was a staple of the Conciliar Revolution in the Church, as it had been of the major political revolutions of the modern world, and was used in all these instances as a form of thought control in order to “recycle” people’s minds and transform their beliefs.

Few people today realize that there are close parallels between the verbal methods of persuasion used by Party leaders of communist regimes, and the sort of language that characterized the decrees of Vatican II and post-conciliar documents emanating from the Vatican and Episcopal Conferences.

In both instances, the selection of words was controlled from the top by leaders who knew how to inculcate their ideological worldview in the minds of the people. The Politburo of both the former Soviet regime and the Chinese Communist Party churned out an array of revolutionary slogans for the people to absorb and repeat.

For its part, Vatican II’s linguistic revolution was also a centrally-controlled top-down process of indoctrination of the masses through the medium of slogans. The Church’s noble tradition of Scholastic expression was ditched and replaced with formulaic politically correct jargon, using slogans devised by the various Commissions and Committees of the Vatican bureaucracy. The ecclesiastical landscape is rife with loaded slogans that have bludgeoned their way into popular usage by the use of brute force.

New vocabularies e.g. “active participation” of the laity, the “community Mass,” the “universal call to holiness,” “faith communities,” “charismatic renewal” and “prophetic witness” were introduced; older terms such as “the common priesthood” and “dialogue” were given new revolutionary meanings; words and phrases such as transubstantiation or the Reign of Christ the King over society were considered politically incorrect – they were suppressed and replaced by “ecumenically correct” slogans such as “Eucharistic celebration,” “freedom of conscience” or the “dignity of man.”

“Serve the People” – perhaps the most famous slogan of the Chinese Communist Party – found a ready acceptance in the Church of the 1960s. It became the leitmotif of the Conciliar and post-Conciliar documents even to the extent of eclipsing the primary duty to serve God first. “Serving the community” is now regarded as the be-all and end-all of the ministerial priesthood, and is now the dominant theme of Pope Francis’s “Synodal Way.”

“Serve the People” – perhaps the most famous slogan of the Chinese Communist Party – found a ready acceptance in the Church of the 1960s. It became the leitmotif of the Conciliar and post-Conciliar documents even to the extent of eclipsing the primary duty to serve God first. “Serving the community” is now regarded as the be-all and end-all of the ministerial priesthood, and is now the dominant theme of Pope Francis’s “Synodal Way.”

Even the slogan of the “inverted pyramid,” which owes its origin to the upheavals of the Russian and Chinese methods of transforming society, was used repeatedly to reinforce a revolutionary message for change in the Church’s Constitution. The key concept here is the struggle for empowerment of the laity, which entails an on-going transfer of ecclesiastical power from the Hierarchy to lay activists in every area of Church life.

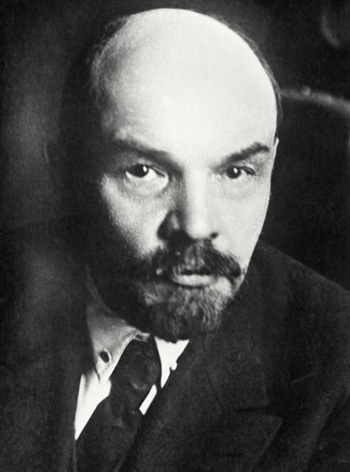

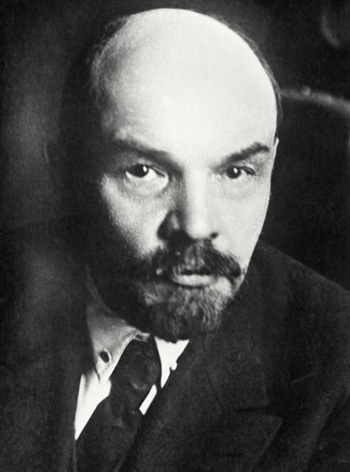

Learning from Lenin

All the evidence indicates that the verbal strategies of Communism, which once characterized Soviet propaganda and the ideology of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, were redeployed to further the aims of Vatican II. No one can deny that they have at least this much in common: they were all conceived in the Marxist-Leninist tradition of creating a permanent revolution to combat and destroy monarchical structures.

This was precisely the aim of the progressivists at Vatican II. Their “inverted pyramid” slogan was a call for a revolution in the Church’s Constitution patterned on the ideas of Lenin, who wrote the following lines two years after the October Revolution of 1917:

This was precisely the aim of the progressivists at Vatican II. Their “inverted pyramid” slogan was a call for a revolution in the Church’s Constitution patterned on the ideas of Lenin, who wrote the following lines two years after the October Revolution of 1917:

“The fundamental law of revolution is as follows: For a revolution to take place it is not enough for the exploited and the oppressed masses to realize the impossibility of living in the old way; for a revolution to take place it is essential that the exploiters should not be able to live and rule in the old way. It is only when the lower classes do not want to live in the old way and the upper classes cannot carry on in the old way that the revolution can triumph,” (1)

We can hear echoes of Leninism in the Catholic Church since the Council, which made sure that the Hierarchy – the ruling body that has the power of orders and jurisdiction – would no longer “live and rule in the old way”: Tiaras are out, class struggle is in. No one, least of all the Pope, can rule “in the old way.”

Documentary evidence abounds to show how Vatican II achieved its own “communistic” revolution by the use of slogans deployed during and after the Council to mount an assault on the sacramental priesthood and lessen its power and effectiveness in the Church. Lenin would certainly have approved of casting aside the Church’s two-tier system of government by hierarchical rulers who exercise spiritual power over their subjects (seen by progressivists as the “oppressed masses”).

If we were to choose one slogan that sums up all the others, it would be “eliminate Clericalism” – a phrase that, though seemingly good in itself, has been subverted to suit the purposes of the Revolution. (This, too, is part of the linguistic strategy that manipulates the mind into accepting a new meaning under the camouflage of the old formula).

What is the meaning of ‘Clericalism’?

There is no clear consensus of the meaning of this word, as it varies with the intention in the mind of the speaker or writer, leaving us to wonder whether it is a real or useful term at all. The fact that “Clericalism” has always been used in a pejorative sense in relation to clerical power, privilege and prestige is highly significant. Its origin is attributed to the French Republican and Freemason, Léon Gambetta, who popularized the mantra “le cléricalisme, voilà l’ennemi (“clericalism is the enemy”) in 1877.

There is no clear consensus of the meaning of this word, as it varies with the intention in the mind of the speaker or writer, leaving us to wonder whether it is a real or useful term at all. The fact that “Clericalism” has always been used in a pejorative sense in relation to clerical power, privilege and prestige is highly significant. Its origin is attributed to the French Republican and Freemason, Léon Gambetta, who popularized the mantra “le cléricalisme, voilà l’ennemi (“clericalism is the enemy”) in 1877.

This paternity essentially stamps it as an anti-clerical trope; it was used only for the purposes of whipping up resentment and hostility to the clergy, especially the Pope, and with the intention of dismantling the Church’s institutional structures.

It is even more highly significant that the word “Clericalism” – like “active participation” (2) before it – was not currency in the Church before Vatican II. Suddenly, people were seeing examples of it popping up everywhere, and rushing to get rid of it, even though it had not been clearly identified. And priests who were merely continuing in their traditional roles and were entirely innocent of any misdemeanor, were declared guilty of the “sin,” “crime” or “sickness” of “Clericalism.”

In fact, under the ever-expanding meaning of the term, there are no traditional positions that will not be marked as “Clericalism” by the reformers. The field has been left wide open to interpretation by those outside the Church who resent the Church’s historic claims, as well as by those inside it who begrudge the clergy their higher status and wish to break free from their spiritual authority.

Before proceeding with the specifics of what constitutes “Clericalism” in the minds of the reformers, let us be clear about the nature of the beast we are about to examine. We are dealing with the new ecclesiology of Vatican II which revolutionized – in the sense of turning upside down – the monarchical nature of the Church, replacing it with a “ministry of all believers” (without being too concerned about what they actually believed).

In the next articles, it will be useful to keep in mind that the Bishops at the Council who called for the rejection of the first schema on the Church’s Constitution did so precisely because it supported the Church’s monarchical structure which they found unacceptable. So they embarked on a campaign of vilification against it, denouncing its two-tiered pyramidal structure as a form of “Clericalism.”

This reveals that the slogan – newly reinvented for the purpose of overturning the Church’s Constitution – was loaded with negative connotations against the clerical estate. We will now deal with the question of whether the motivations and attitudes that the progressivists ascribe to the clergy are real or merely perceived.

Continued

Few people today realize that there are close parallels between the verbal methods of persuasion used by Party leaders of communist regimes, and the sort of language that characterized the decrees of Vatican II and post-conciliar documents emanating from the Vatican and Episcopal Conferences.

In both instances, the selection of words was controlled from the top by leaders who knew how to inculcate their ideological worldview in the minds of the people. The Politburo of both the former Soviet regime and the Chinese Communist Party churned out an array of revolutionary slogans for the people to absorb and repeat.

For its part, Vatican II’s linguistic revolution was also a centrally-controlled top-down process of indoctrination of the masses through the medium of slogans. The Church’s noble tradition of Scholastic expression was ditched and replaced with formulaic politically correct jargon, using slogans devised by the various Commissions and Committees of the Vatican bureaucracy. The ecclesiastical landscape is rife with loaded slogans that have bludgeoned their way into popular usage by the use of brute force.

New vocabularies e.g. “active participation” of the laity, the “community Mass,” the “universal call to holiness,” “faith communities,” “charismatic renewal” and “prophetic witness” were introduced; older terms such as “the common priesthood” and “dialogue” were given new revolutionary meanings; words and phrases such as transubstantiation or the Reign of Christ the King over society were considered politically incorrect – they were suppressed and replaced by “ecumenically correct” slogans such as “Eucharistic celebration,” “freedom of conscience” or the “dignity of man.”

The Conciliar Revolution adopted the verbiage of the Chinese Communist Party: Serve the People

Even the slogan of the “inverted pyramid,” which owes its origin to the upheavals of the Russian and Chinese methods of transforming society, was used repeatedly to reinforce a revolutionary message for change in the Church’s Constitution. The key concept here is the struggle for empowerment of the laity, which entails an on-going transfer of ecclesiastical power from the Hierarchy to lay activists in every area of Church life.

Learning from Lenin

All the evidence indicates that the verbal strategies of Communism, which once characterized Soviet propaganda and the ideology of the Chinese Cultural Revolution, were redeployed to further the aims of Vatican II. No one can deny that they have at least this much in common: they were all conceived in the Marxist-Leninist tradition of creating a permanent revolution to combat and destroy monarchical structures.

Lenin: ‘The exploiters should not be able to live & rule in the old way’

“The fundamental law of revolution is as follows: For a revolution to take place it is not enough for the exploited and the oppressed masses to realize the impossibility of living in the old way; for a revolution to take place it is essential that the exploiters should not be able to live and rule in the old way. It is only when the lower classes do not want to live in the old way and the upper classes cannot carry on in the old way that the revolution can triumph,” (1)

We can hear echoes of Leninism in the Catholic Church since the Council, which made sure that the Hierarchy – the ruling body that has the power of orders and jurisdiction – would no longer “live and rule in the old way”: Tiaras are out, class struggle is in. No one, least of all the Pope, can rule “in the old way.”

Documentary evidence abounds to show how Vatican II achieved its own “communistic” revolution by the use of slogans deployed during and after the Council to mount an assault on the sacramental priesthood and lessen its power and effectiveness in the Church. Lenin would certainly have approved of casting aside the Church’s two-tier system of government by hierarchical rulers who exercise spiritual power over their subjects (seen by progressivists as the “oppressed masses”).

If we were to choose one slogan that sums up all the others, it would be “eliminate Clericalism” – a phrase that, though seemingly good in itself, has been subverted to suit the purposes of the Revolution. (This, too, is part of the linguistic strategy that manipulates the mind into accepting a new meaning under the camouflage of the old formula).

What is the meaning of ‘Clericalism’?

Gambetta targeted clericalism as the main enemy

of French Freemasonry

This paternity essentially stamps it as an anti-clerical trope; it was used only for the purposes of whipping up resentment and hostility to the clergy, especially the Pope, and with the intention of dismantling the Church’s institutional structures.

It is even more highly significant that the word “Clericalism” – like “active participation” (2) before it – was not currency in the Church before Vatican II. Suddenly, people were seeing examples of it popping up everywhere, and rushing to get rid of it, even though it had not been clearly identified. And priests who were merely continuing in their traditional roles and were entirely innocent of any misdemeanor, were declared guilty of the “sin,” “crime” or “sickness” of “Clericalism.”

In fact, under the ever-expanding meaning of the term, there are no traditional positions that will not be marked as “Clericalism” by the reformers. The field has been left wide open to interpretation by those outside the Church who resent the Church’s historic claims, as well as by those inside it who begrudge the clergy their higher status and wish to break free from their spiritual authority.

Before proceeding with the specifics of what constitutes “Clericalism” in the minds of the reformers, let us be clear about the nature of the beast we are about to examine. We are dealing with the new ecclesiology of Vatican II which revolutionized – in the sense of turning upside down – the monarchical nature of the Church, replacing it with a “ministry of all believers” (without being too concerned about what they actually believed).

In the next articles, it will be useful to keep in mind that the Bishops at the Council who called for the rejection of the first schema on the Church’s Constitution did so precisely because it supported the Church’s monarchical structure which they found unacceptable. So they embarked on a campaign of vilification against it, denouncing its two-tiered pyramidal structure as a form of “Clericalism.”

This reveals that the slogan – newly reinvented for the purpose of overturning the Church’s Constitution – was loaded with negative connotations against the clerical estate. We will now deal with the question of whether the motivations and attitudes that the progressivists ascribe to the clergy are real or merely perceived.

Continued

- Vladimir Ilich Lenin, On Culture and Cultural Revolution, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1970, p. 94.

- For a detailed analysis of the history of “active participation” as a liturgical slogan, see the first two chapters of my book Born of Revolution: A Misconceived Liturgical Reform, Volume I, Holyrood Press, 2020..

Posted August 12, 2022

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |