Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XCIII

The Loreto Tradition Is Not a Legend

Myth still tends to be associated with the Loreto tradition, and accusations are rife in the modern era that it was a pure invention, impossible to reconcile with the nature of historical reality. This was the position of the 20th century modernists who acted on the assumption that miracles should not be taken into account if we are setting out to do “scholarly” work on past events and determine their historicity. And it is still the prevalent view among progressivist Catholics today.

But, in cutting themselves off from the supernatural sources of divine intervention, they also severed any ties to what is most true about the world of reality, which they claim they can explain to others.

The main charge – falsely levelled against the Loreto tradition – was that of credulity on the part of those who accepted it in the absence of reasonable proof or knowledge. To defend the tradition, we will show that there are grounds for both a truly Catholic and intellectually respectable belief that the Holy House was transported miraculously from Nazareth, with various stops along the way, to Loreto.

The main charge – falsely levelled against the Loreto tradition – was that of credulity on the part of those who accepted it in the absence of reasonable proof or knowledge. To defend the tradition, we will show that there are grounds for both a truly Catholic and intellectually respectable belief that the Holy House was transported miraculously from Nazareth, with various stops along the way, to Loreto.

In the first place, it is necessary to accept that it is possible for God to operate outside the laws that govern the physical world without violating the natural order; and that the miracles He wills to perform are not contrary to nature but above and beyond nature. Once that fundamental point is accepted, we move on to the inescapable conclusion that the possibility of such an event happening cannot be regarded as absurd by anyone who believes in Divine Providence and the ministry of Angels.

We will proceed in our enquiry on the basis that this tradition has a claim to serious consideration, especially by Catholics.

Let us consider the following facts that constitute convincing evidence for the authenticity of the miraculous translocations of the Holy House at the end of the 13th century: Each of these pieces of evidence carries great epistemological weight; together, they have an internal consistency that confers on the whole Loreto tradition a definite logical validity. Who, indeed, with any cogency can argue against them? It has never been done, as we shall see later when examining the counter-claims of various “Loreto sceptics.”

Each of these pieces of evidence carries great epistemological weight; together, they have an internal consistency that confers on the whole Loreto tradition a definite logical validity. Who, indeed, with any cogency can argue against them? It has never been done, as we shall see later when examining the counter-claims of various “Loreto sceptics.”

The 19th-century priest Fr. James Spencer Northcote, (2) an expert in Christian antiquities and a noted archaeologist, having studied the history of the Holy House, concluded that anyone who poured scorn on its miraculous Translation would find himself in an invidious position:

“He is assuming that he is more intelligent than the great body of the faithful who for centuries have venerated this sanctuary and have regarded its history as true. He is assuming that he is more sagacious than the Saints, wiser than the Supreme Pontiffs who have rendered such magnificent testimonies to the truth of its history, and more prudent than the Sacred Congregation of Rites who have approved the office of the translation.” (3)

Anyone who rejects the concept of the miraculous flight – or, more correctly, multiple “flights” – of the Holy House, without first considering the accumulated evidence offered by the Church, could aptly be accused of either irrationality or ill will.

Documents may perish, but tradition survives

If one expects to consult a set of contemporary documents describing the disappearance of the House from Nazareth in 1291 and its eventual appearance in Loreto in 1295, he would be much disappointed, for the original source material produced at the time of the Translation was either lost or destroyed; and there were no published historical accounts of the Translation until the 15th century.

This does not, however, give grounds for disbelief, as the credibility of miracles rests on a different sort of evidence than that provided by modern “revisionist historians” who assess the events in purely naturalistic terms.

This point was made by Pope Pius X in a letter addressed through the Cardinal Secretary of State to the Archbishop of Rouen in which he mentioned “the fundamental principles and the rules of the true historical and apologetic method made, with the doctrinal authority appertaining to their persons and their mission, by those whose pride and duty it is to put themselves at the head of the defenders of pure orthodoxy.” (4) In other words, credibility rests on the authority of Church leaders who uphold orthodox doctrine.

This point was made by Pope Pius X in a letter addressed through the Cardinal Secretary of State to the Archbishop of Rouen in which he mentioned “the fundamental principles and the rules of the true historical and apologetic method made, with the doctrinal authority appertaining to their persons and their mission, by those whose pride and duty it is to put themselves at the head of the defenders of pure orthodoxy.” (4) In other words, credibility rests on the authority of Church leaders who uphold orthodox doctrine.

He warned that the credibility of supernatural truths cannot be found in “the pompous pretext of a vain erudition” that comes from pseudo-science, and encouraged “well-intentioned persons … to discover, even in the absence of written documents, the manifest proofs of the truth of what is believed on the basis of tradition prudently overseen and verified.” (5) [emphasis added]

But, what sort of evidence was there originally, and how convincing is it, given the non-survival of the first documents? Certain historians of the 15th century, encouraged by the protection and oversight of popes, had consulted and recorded many of the testimonies from 13th-century pilgrims to both Nazareth and Loreto, ensuring that these survived even after the loss of the original documents.

From these we gather that successions of pilgrims who had visited Nazareth before 1291 concurred in their testimonies that the Holy House was located in the crypt of a basilica that had been built over it by the Crusaders. It was there that St. Louis IX, King of France, heard Mass in 1251 in the same chamber where the Angel announced the coming of Christ to the Blessed Virgin Mary. (6) The tradition of using the Holy House as a church continued after its relocation to Loreto where it, too, became a site of pilgrimage for thousands of Catholics from around the world.

What is the ‘Loreto tradition’?

The earliest written history of the Loreto Sanctuary dates from the mid-15th century when Fr. Pietro di Giorgio Tolomei (usually known as Teramano), its rector from 1450-1473, produced his account in Latin, based on information found in the local archives. (7)

It started life as a modest Summary hung on the wall of the House-cum-church for the information of visiting pilgrims, but achieved international fame after it was published in Italian in 1472. (8) The value of Teramano’s account was that it provided posterity with a chronicle of the living tradition of his day, which had been bruited around since 1291. This source, therefore, can be regarded as the basis of the whole Loreto tradition.

It started life as a modest Summary hung on the wall of the House-cum-church for the information of visiting pilgrims, but achieved international fame after it was published in Italian in 1472. (8) The value of Teramano’s account was that it provided posterity with a chronicle of the living tradition of his day, which had been bruited around since 1291. This source, therefore, can be regarded as the basis of the whole Loreto tradition.

It can be divided into three main sections.

First, Teramano traced in detail the journey of the Holy House from Nazareth via Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia) and various places in Italy to its location in Loreto near the town of Recanati. His information was based not only on a thorough search into the archival documents, but also on statements, made under oath, by trustworthy locals who reported what previous generations had seen and heard at the time of the various translations of the Holy House.

The credibility of their testimony rested mainly on the medieval principle of fidedignorum assertio (a statement made by “trustworthy men”). (9) Eye witness evidence was not enough to produce moral certainty; it had to concur with faith in invisible things and corroborate the already existing tradition. This had been handed down and universally accepted by the inhabitants of the areas through which the Holy House had passed, and by the large number of pilgrims who had witnessed miracles in those places.

Second, Teramano devoted a section to the words of a local hermit of devout life who described a revelation he had received from Our Lady concerning the Holy House: that it was hers, the place of the Incarnation and the home of the Holy Family.

Third, Teramano also mentioned that a 16-man delegation was sent from Recanati in 1296 to inspect the site of the Nazareth House where, it transpired, only the foundations remained; that they took measurements and, upon their return, found that these corresponded exactly (“ad unguem”) (10) to the dimensions of the Holy House that had departed Nazareth, leaving its foundations behind.

That is the Loreto tradition in a nutshell. It may not seem much to go on, but once the implications have been drawn from the information supplied, and when further research was carried out ‒ which, as we shall see, was the work of later historians and scientists ‒ the results are simply stupendous. It means that the Holy House, contrary to the laws of physics, has stood without foundations and completely unsupported for centuries as its own silent witness to its sacred character and miraculous transportation.

What we can say so far with certainty is that the Loreto tradition, passed down from mouth to mouth as a series of known occurrences duly witnessed, signed and archived before being chronicled by Teramano, was no mere “legend” or fanciful invention.

Continued

Continued

But, in cutting themselves off from the supernatural sources of divine intervention, they also severed any ties to what is most true about the world of reality, which they claim they can explain to others.

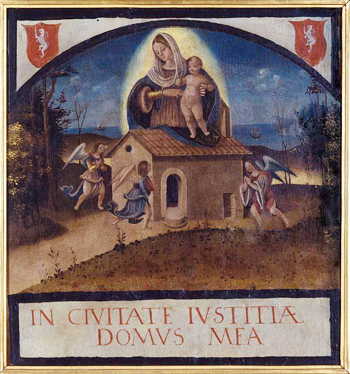

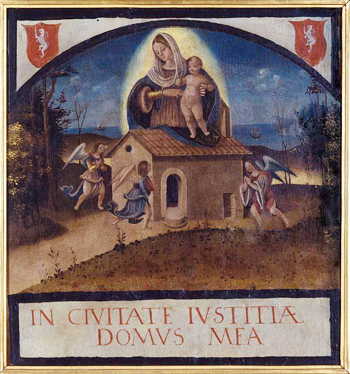

A 1520 illustration showing the translation of the Holy House to Loreto

In the first place, it is necessary to accept that it is possible for God to operate outside the laws that govern the physical world without violating the natural order; and that the miracles He wills to perform are not contrary to nature but above and beyond nature. Once that fundamental point is accepted, we move on to the inescapable conclusion that the possibility of such an event happening cannot be regarded as absurd by anyone who believes in Divine Providence and the ministry of Angels.

We will proceed in our enquiry on the basis that this tradition has a claim to serious consideration, especially by Catholics.

Let us consider the following facts that constitute convincing evidence for the authenticity of the miraculous translocations of the Holy House at the end of the 13th century:

- Oral testimonies approved by the Church less than 20 years after the arrival of the Holy House in Loreto;

- The testimony of the innumerable miracles wrought in the Holy House and the Divine favors granted there;

- An unbroken tradition of acceptance by the Catholic world for over 700 years;

- The devotion of hundreds of Saints (1) and countless pilgrims who visited the site;

- Scholarly evaluation of the historical records;

- Valid scientific evidence obtained from expert analysis of the fabric of the Holy House proving its origin in Palestine and the impossibility of its being rebuilt in Loreto;

- Statements of over 40 Roman Pontiffs in official documents declaring the identity of the Holy House of Nazareth and that of Loreto, and granting indulgences to pilgrims;

- The concession of a Proper Office and Mass in 1699.

The miraculous statue of the Madonna of Loreto in the Basilica that covers the Holy House

The 19th-century priest Fr. James Spencer Northcote, (2) an expert in Christian antiquities and a noted archaeologist, having studied the history of the Holy House, concluded that anyone who poured scorn on its miraculous Translation would find himself in an invidious position:

“He is assuming that he is more intelligent than the great body of the faithful who for centuries have venerated this sanctuary and have regarded its history as true. He is assuming that he is more sagacious than the Saints, wiser than the Supreme Pontiffs who have rendered such magnificent testimonies to the truth of its history, and more prudent than the Sacred Congregation of Rites who have approved the office of the translation.” (3)

Anyone who rejects the concept of the miraculous flight – or, more correctly, multiple “flights” – of the Holy House, without first considering the accumulated evidence offered by the Church, could aptly be accused of either irrationality or ill will.

Documents may perish, but tradition survives

If one expects to consult a set of contemporary documents describing the disappearance of the House from Nazareth in 1291 and its eventual appearance in Loreto in 1295, he would be much disappointed, for the original source material produced at the time of the Translation was either lost or destroyed; and there were no published historical accounts of the Translation until the 15th century.

This does not, however, give grounds for disbelief, as the credibility of miracles rests on a different sort of evidence than that provided by modern “revisionist historians” who assess the events in purely naturalistic terms.

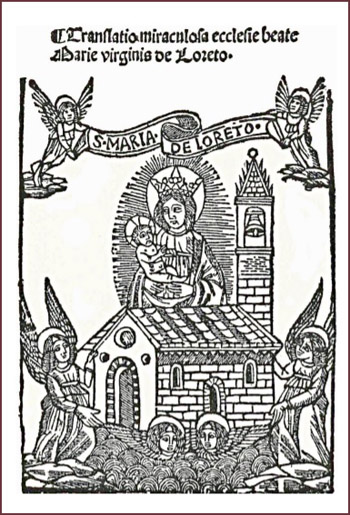

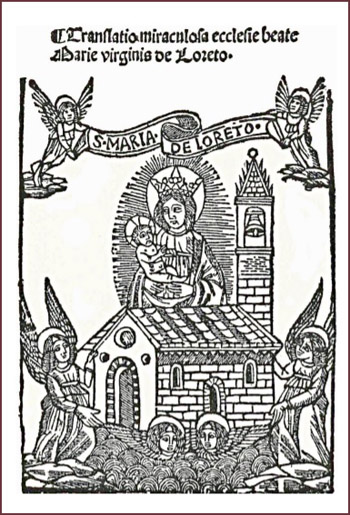

A 16th century map showing the double translation

of the Holy House

He warned that the credibility of supernatural truths cannot be found in “the pompous pretext of a vain erudition” that comes from pseudo-science, and encouraged “well-intentioned persons … to discover, even in the absence of written documents, the manifest proofs of the truth of what is believed on the basis of tradition prudently overseen and verified.” (5) [emphasis added]

But, what sort of evidence was there originally, and how convincing is it, given the non-survival of the first documents? Certain historians of the 15th century, encouraged by the protection and oversight of popes, had consulted and recorded many of the testimonies from 13th-century pilgrims to both Nazareth and Loreto, ensuring that these survived even after the loss of the original documents.

From these we gather that successions of pilgrims who had visited Nazareth before 1291 concurred in their testimonies that the Holy House was located in the crypt of a basilica that had been built over it by the Crusaders. It was there that St. Louis IX, King of France, heard Mass in 1251 in the same chamber where the Angel announced the coming of Christ to the Blessed Virgin Mary. (6) The tradition of using the Holy House as a church continued after its relocation to Loreto where it, too, became a site of pilgrimage for thousands of Catholics from around the world.

What is the ‘Loreto tradition’?

The earliest written history of the Loreto Sanctuary dates from the mid-15th century when Fr. Pietro di Giorgio Tolomei (usually known as Teramano), its rector from 1450-1473, produced his account in Latin, based on information found in the local archives. (7)

Above, first page of the 15th century manuscript of Fr. Termano, below, a 14th century tin alloy

It can be divided into three main sections.

First, Teramano traced in detail the journey of the Holy House from Nazareth via Dalmatia (modern-day Croatia) and various places in Italy to its location in Loreto near the town of Recanati. His information was based not only on a thorough search into the archival documents, but also on statements, made under oath, by trustworthy locals who reported what previous generations had seen and heard at the time of the various translations of the Holy House.

The credibility of their testimony rested mainly on the medieval principle of fidedignorum assertio (a statement made by “trustworthy men”). (9) Eye witness evidence was not enough to produce moral certainty; it had to concur with faith in invisible things and corroborate the already existing tradition. This had been handed down and universally accepted by the inhabitants of the areas through which the Holy House had passed, and by the large number of pilgrims who had witnessed miracles in those places.

Second, Teramano devoted a section to the words of a local hermit of devout life who described a revelation he had received from Our Lady concerning the Holy House: that it was hers, the place of the Incarnation and the home of the Holy Family.

Third, Teramano also mentioned that a 16-man delegation was sent from Recanati in 1296 to inspect the site of the Nazareth House where, it transpired, only the foundations remained; that they took measurements and, upon their return, found that these corresponded exactly (“ad unguem”) (10) to the dimensions of the Holy House that had departed Nazareth, leaving its foundations behind.

That is the Loreto tradition in a nutshell. It may not seem much to go on, but once the implications have been drawn from the information supplied, and when further research was carried out ‒ which, as we shall see, was the work of later historians and scientists ‒ the results are simply stupendous. It means that the Holy House, contrary to the laws of physics, has stood without foundations and completely unsupported for centuries as its own silent witness to its sacred character and miraculous transportation.

What we can say so far with certainty is that the Loreto tradition, passed down from mouth to mouth as a series of known occurrences duly witnessed, signed and archived before being chronicled by Teramano, was no mere “legend” or fanciful invention.

The subject of numerous paintings and illustrations

- Among these were St. Francis Xavier, St. Ignatius Loyola, St. Charles Borromeo, St. Aloysius Gonzaga, St. Francis de Sales, St. Benedict Labre, St. Alphonsus Liguori and St. Teresa of Lisieux.

- Fr. James Spencer Northcote DD (1821-1907) was a convert from Anglicanism. He was a distinguished Classical scholar with a First Class degree from Oxford University, and later became interested in archaeology. In recognition of his erudition, he received the title Doctor of Divinity in 1861 from Pope Pius IX, and he was made President of Oscott College in the Diocese of Birmingham.

- J.S. Northcote, Celebrated Sanctuaries of the Madonna, P.F. Cunningham, 1868, p. 102.

- AAS, 04, 1912, Letter from Card. Merry del Val to Arch. Frédéric Fuzet of Rouen, 22 April, p. 355.

- Ibid.

- An account of the King’s visit to Nazareth was written by his confessor and biographer, Geoffroy de Beaulieu, OP, who accompanied him during his pilgrimage to the Holy Land. His biography, Vita Ludovici Noni (The Life of Louis IX) was one of the principal testimonies in the process of Louis IX’s canonization, which took place in 1297.

- Around the same time, another history, similar in content to Teramano’s, was written by Fr. Giacomo Ricci, but it was little known because it remained for centuries in manuscript form. It was not published until 1987 under its original title of Virginis Mariae Loretae Historia.

- As a measure of how highly Teramano’s Summary was prized by the Holy See, it was translated in 1578 on the orders of Pope Gregory XIII into Greek, Arabic, Slavic, German, French and Spanish, and fixed to the walls of the Sanctuary for the benefit of international pilgrims. It would later be translated into English.

- In the Middle Ages, it was the common practice for bishops to gather information from statements made by witnesses in ecclesiastical courts, during episcopal visitations and before Inquisition tribunals. Such statements were held on trust based on a common background of religious faith. Bishops placed faith in local men deemed worthy of their trust who, in turn, recognized the bishop’s authority and power of jurisdiction.

- Teramano used this expression (literally “to the nail”) to denote a perfect fit. As a metaphor drawn from architecture, it was commonly used in Roman times by sculptors and stonemasons who tested the perfection of their work by gliding a finger nail across a well-fitting joint.

Posted April 6, 2020

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |