Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXXII

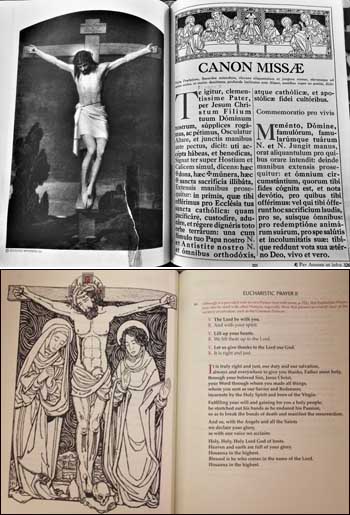

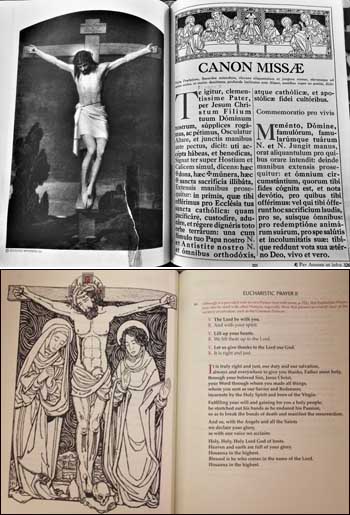

The 1962 Canon Precipitated a Crisis

What started as a campaign by devotees of St. Joseph for increased liturgical honors entered a whole new dimension in 1962 with the “bombshell” announcement by Pope John XXIII to include St. Joseph’s name in the Canon of the Mass.

From then on, the word Canon could not properly be used in its old sense, since the invariable rule no longer applied. It was obviously a misnomer as it now reflected the drive for change, fulfilling the exact opposite purpose for which it was originally intended.

From then on, the word Canon could not properly be used in its old sense, since the invariable rule no longer applied. It was obviously a misnomer as it now reflected the drive for change, fulfilling the exact opposite purpose for which it was originally intended.

Quite logically, the reformers soon dropped the name Canon and, after making further changes, re-named it “Eucharistic Prayer 1.” But even before the New Mass, the concept of the Roman Canon had been destroyed. Bugnini wrote exultantly:

“The concept of a liturgy tied to rubrics and ceremonies, fixed in its formulas and divorced from reality has definitely given place to a dynamic concept of worship, alive and vital, biblical and pastoral, traditional and contemporary; anchored to a healthy past, but straining towards the future. And from this onward march, indicated by the Council and effected by the Consilium, the Church is not going to deviate.” (1)

So, Bugnini had his way after all, with grave implications for future reforms.

Confiteor before Communion

This Confiteor, together with the Absolution, had been in use centuries before the Council of Trent and was mandated in the rubrics of the Tridentine Missal to be said before the distribution of Holy Communion to the faithful. (2) In spite of its great antiquity, it was suppressed by Pope John XXIII in 1960 (3) as part of the “simplification” of the Roman Rite planned by Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission which, as we have seen, was merely an echo-chamber for progressivist opinion.

Fr. Josef Jungmann, one of the advisors to that Commission, termed the Confiteor before Communion “a rather unnecessary repetition,” (4) given that the Confiteor had already been said twice at the beginning of the Mass – first by the priest and then by the server.

But Jungmann’s opinion was a gross mischaracterization, as none of these Confiteors was either unnecessary or a mere repetition. Each had its allotted space in the scheme of the liturgy for a particular purpose: to safeguard the meaning of the Mass and the Priesthood from misinterpretation.

But Jungmann’s opinion was a gross mischaracterization, as none of these Confiteors was either unnecessary or a mere repetition. Each had its allotted space in the scheme of the liturgy for a particular purpose: to safeguard the meaning of the Mass and the Priesthood from misinterpretation.

Each of the three Confiteors is a discrete entity with its own raison d’être, employed for specific theological and spiritual reasons, and was necessary within its own frame of reference. (8)

The purpose was, first, to distinguish the priesthood of the ordained minister from the lay members of the congregation and, secondly, to make clear the distinction between the Sacrifice of the Mass celebrated by the priest, and the Sacrament of the Eucharist received by the faithful. Mgr. Gromier pointed out: “the enormous difference between the two uses of the Confiteor.” (9) It makes no sense, therefore, to say that the Confiteor before Communion is an “unnecessary repetition” of previously recited prayers.

The purpose was, first, to distinguish the priesthood of the ordained minister from the lay members of the congregation and, secondly, to make clear the distinction between the Sacrifice of the Mass celebrated by the priest, and the Sacrament of the Eucharist received by the faithful. Mgr. Gromier pointed out: “the enormous difference between the two uses of the Confiteor.” (9) It makes no sense, therefore, to say that the Confiteor before Communion is an “unnecessary repetition” of previously recited prayers.

Besides, these distinctions needed to be made clear because they were the target for attack by the 16th century Protestant Reformers and were rejected by progressivist liturgists of the 20th who paved the way for the Novus Ordo Mass via the 1962 Missal.

In 1943, Archbishop Conrad Gröber of Fribourg revealed the real reason for the desire to suppress the Confiteor before Communion. In his critical Memorandum circulated to the Bishops of the German-speaking countries and also to Pope Pius XII, (10) he objected that the reformers “presented the Communion of the faithful as an integral part of the Mass.” (11) This indicates that receptiveness to Protestant ideas about the Mass was, to use a phrase of Pope Pius X, beginning to spread into “the very veins and heart of the Church.” (12)

Antecedents of the suppression of the Confiteor

We can trace the development of this non-Catholic theological principle, starting from the early leaders of the Liturgical Movement – notably Frs. Pius Parsch (13) and Josef Jungmann (14) in the 1940s – through the Missal of John XXIII, up to and including Paul VI’s New Mass.

The Confiteor before Communion was obviously a major issue for the reformers, as it wasfeatured in all the main international Liturgical Congresses from Maria Laach (1951) to Assisi (1956) (15) (See here)). Its abolition was sought in order to give the impression that the people’s Communion was as much part of the Mass as any other element. This is clear from a speech given shortly before the Lugano Congress (1953) by Fr. Josef Löw, the Vice-Relator of the Congregation of Rites and member of Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission, in which he stated:

The Confiteor before Communion was obviously a major issue for the reformers, as it wasfeatured in all the main international Liturgical Congresses from Maria Laach (1951) to Assisi (1956) (15) (See here)). Its abolition was sought in order to give the impression that the people’s Communion was as much part of the Mass as any other element. This is clear from a speech given shortly before the Lugano Congress (1953) by Fr. Josef Löw, the Vice-Relator of the Congregation of Rites and member of Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission, in which he stated:

“At the Communion, the Confiteor and the Misereatur are expected to disappear … the Communion [of the people] is, after all, a part of the Mass.” (16)

This was the general opinion of the progressivist reformers, and Pius XII took the first tentative step in granting their wishes by eliminating the Confiteor and Absolution in the Maundy Thursday Mass in the reformed Holy Week of 1956. (17) In so doing, he allowed a heterodox notion of the reformers to promote itself as an influential force in the liturgy.

John XXIII’s reform went much further: he extended it to every celebration of the Mass (except on Good Friday and at Ordinations).

Effects of the reform

Unlike the insertion of St. Joseph in the Canon, recited inaudibly by the priest, the suppression of this Confiteor was a highly conspicuous change, evident to the whole congregation. As such, its effect on the faithful was bound to be significant.

When John XXIII abolished the Confiteor before Communion on the spurious grounds of “simplification,” he undermined a teaching of the Church of which this immemorial custom was the external and visible sign: only the priest’s Communion is required for the completion of the Sacrifice, and belongs not to the essence but to the integrity of the Mass.

It follows that this Confiteor should remain in place as evidence that the people’s Communion is not an integral part of the Mass. Its omission aids the impression ‒ enthusiastically encouraged by the reformers ‒ that the Mass is fundamentally a Communion Service, (18) and that the Communion of the people is as much part of the Mass as the priest’s. Consequently, it is commonly assumed today that if one cannot receive Communion, there is no point in going to Mass at all.

It follows that this Confiteor should remain in place as evidence that the people’s Communion is not an integral part of the Mass. Its omission aids the impression ‒ enthusiastically encouraged by the reformers ‒ that the Mass is fundamentally a Communion Service, (18) and that the Communion of the people is as much part of the Mass as the priest’s. Consequently, it is commonly assumed today that if one cannot receive Communion, there is no point in going to Mass at all.

John XXIII’s ill-conceived reform was an identifiable element in facilitating widespread doctrinal confusion about what the Mass really is, and smoothed the way for the reformers to gain acceptance for their “Banquet theory,” which predominates today.

After years of Orwellian double-think in which both the Mass and Communion are equally called “the Eucharist,” few can be expected to tell the difference between the Sacrifice of the Mass per se and the people’s reception of Holy Communion during it.

An intentional omission

When we consider this end result and go backwards to 1962, it becomes clear how and why this subtle elision of terms – and consequent confusion about the meaning of the Mass – is connected with the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion.

John XXIII was not unaware that what he was omitting was pertinent to a correct understanding of the Mass. The reformers, for their part, had a specific motive for its removal: to change the doctrine of the Mass as the Holy Sacrifice offered by a priest on the altar to a meal shared among everyone “gathered around the table,” with the emphasis on the supposedly “essential” role the assembly plays in “celebrating the Eucharist.”

Thus, in this one reform, two deceptions were combined – not only hiding the truth about the Mass but also promoting a falsity to be believed as truth.

There is no suggestion here that the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion single-handedly caused a doctrinal crisis. But given the antecedents and consequences of this reform, no one can reasonably deny that it was a significant contributory factor in bringing it about, or claim that it was a harmless example of “simplification” of the Roman Rite.

Continued

From the unchangeable Canon Missae to the ‘Eucharistic Prayer’ in various forms

Quite logically, the reformers soon dropped the name Canon and, after making further changes, re-named it “Eucharistic Prayer 1.” But even before the New Mass, the concept of the Roman Canon had been destroyed. Bugnini wrote exultantly:

“The concept of a liturgy tied to rubrics and ceremonies, fixed in its formulas and divorced from reality has definitely given place to a dynamic concept of worship, alive and vital, biblical and pastoral, traditional and contemporary; anchored to a healthy past, but straining towards the future. And from this onward march, indicated by the Council and effected by the Consilium, the Church is not going to deviate.” (1)

So, Bugnini had his way after all, with grave implications for future reforms.

Confiteor before Communion

This Confiteor, together with the Absolution, had been in use centuries before the Council of Trent and was mandated in the rubrics of the Tridentine Missal to be said before the distribution of Holy Communion to the faithful. (2) In spite of its great antiquity, it was suppressed by Pope John XXIII in 1960 (3) as part of the “simplification” of the Roman Rite planned by Pius XII’s Liturgical Commission which, as we have seen, was merely an echo-chamber for progressivist opinion.

Fr. Josef Jungmann, one of the advisors to that Commission, termed the Confiteor before Communion “a rather unnecessary repetition,” (4) given that the Confiteor had already been said twice at the beginning of the Mass – first by the priest and then by the server.

Servers say the Confiteor representing all present at the Holy Mass

- The first Confiteor is recited by the priest to express his own unworthiness to offer the Holy Sacrifice;

- The second is said by the Ministers (or server at Low Mass in their stead) to dispose themselves and all present to assist at it worthily;

- The third expresses sorrow for sin on the part of those intending to receive Holy Communion, and is part of a separate rite taken from the Rituale Romanum for the purpose of administering the Sacrament to the faithful. (5) It is significant that this Confiteor (followed by Ecce Agnus Dei and the threefold Domine non sum dignus) was not included in the Order of Mass itself, (6) for the simple reason that only the priest’s Communion is necessary for the completion of the Sacrifice. (7)

Each of the three Confiteors is a discrete entity with its own raison d’être, employed for specific theological and spiritual reasons, and was necessary within its own frame of reference. (8)

Acts of humility such as the Confiteor were distasteful to Protestant and Progressivist reformers

Besides, these distinctions needed to be made clear because they were the target for attack by the 16th century Protestant Reformers and were rejected by progressivist liturgists of the 20th who paved the way for the Novus Ordo Mass via the 1962 Missal.

In 1943, Archbishop Conrad Gröber of Fribourg revealed the real reason for the desire to suppress the Confiteor before Communion. In his critical Memorandum circulated to the Bishops of the German-speaking countries and also to Pope Pius XII, (10) he objected that the reformers “presented the Communion of the faithful as an integral part of the Mass.” (11) This indicates that receptiveness to Protestant ideas about the Mass was, to use a phrase of Pope Pius X, beginning to spread into “the very veins and heart of the Church.” (12)

Antecedents of the suppression of the Confiteor

We can trace the development of this non-Catholic theological principle, starting from the early leaders of the Liturgical Movement – notably Frs. Pius Parsch (13) and Josef Jungmann (14) in the 1940s – through the Missal of John XXIII, up to and including Paul VI’s New Mass.

Fr. Josef Löw: ‘The Confiteor before Communion will have to disappear’

“At the Communion, the Confiteor and the Misereatur are expected to disappear … the Communion [of the people] is, after all, a part of the Mass.” (16)

This was the general opinion of the progressivist reformers, and Pius XII took the first tentative step in granting their wishes by eliminating the Confiteor and Absolution in the Maundy Thursday Mass in the reformed Holy Week of 1956. (17) In so doing, he allowed a heterodox notion of the reformers to promote itself as an influential force in the liturgy.

John XXIII’s reform went much further: he extended it to every celebration of the Mass (except on Good Friday and at Ordinations).

Effects of the reform

Unlike the insertion of St. Joseph in the Canon, recited inaudibly by the priest, the suppression of this Confiteor was a highly conspicuous change, evident to the whole congregation. As such, its effect on the faithful was bound to be significant.

When John XXIII abolished the Confiteor before Communion on the spurious grounds of “simplification,” he undermined a teaching of the Church of which this immemorial custom was the external and visible sign: only the priest’s Communion is required for the completion of the Sacrifice, and belongs not to the essence but to the integrity of the Mass.

A ‘banquet’ Mass where even youth hand out communion

John XXIII’s ill-conceived reform was an identifiable element in facilitating widespread doctrinal confusion about what the Mass really is, and smoothed the way for the reformers to gain acceptance for their “Banquet theory,” which predominates today.

After years of Orwellian double-think in which both the Mass and Communion are equally called “the Eucharist,” few can be expected to tell the difference between the Sacrifice of the Mass per se and the people’s reception of Holy Communion during it.

An intentional omission

When we consider this end result and go backwards to 1962, it becomes clear how and why this subtle elision of terms – and consequent confusion about the meaning of the Mass – is connected with the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion.

John XXIII was not unaware that what he was omitting was pertinent to a correct understanding of the Mass. The reformers, for their part, had a specific motive for its removal: to change the doctrine of the Mass as the Holy Sacrifice offered by a priest on the altar to a meal shared among everyone “gathered around the table,” with the emphasis on the supposedly “essential” role the assembly plays in “celebrating the Eucharist.”

Thus, in this one reform, two deceptions were combined – not only hiding the truth about the Mass but also promoting a falsity to be believed as truth.

There is no suggestion here that the suppression of the Confiteor before Communion single-handedly caused a doctrinal crisis. But given the antecedents and consequences of this reform, no one can reasonably deny that it was a significant contributory factor in bringing it about, or claim that it was a harmless example of “simplification” of the Roman Rite.

Continued

- A. Bugnini, ‘The Consilium and Liturgical Reform’, The Furrow, March 19, 1968, p. 177. The Furrow was an Irish theological journal founded in 1950 which, as its title suggests, broke new ground. It spearheaded the liturgical reform in Ireland. Interestingly, its Editor, Fr. J. G. McGarry, observed in 1956 when Pius XII’s Holy Week reforms came into effect: “There is not yet in Ireland any coherent group advocating the Liturgy, or any sign of the emergence of such a group.” (‘The Liturgy in Ireland,’ Worship, vol. XXXI, no. 7, 1956/ 1957, p. 409) But that situation would soon be changed with the top-down, dictatorial imposition of the liturgical reform.

- Ritus servandus in celebratione Missae, X, 6.

- Sacred Congregation of Rites, Novum Rubricarum § 503, A.A.S. 52, July 26, 1960, p. 680.

- Josef Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 2, p. 373.

- Up until the modern age, Catholics did not always receive Communion during Mass; it was sometimes distributed before or after Mass. Whatever the arrangement, it was preceded by a separate rite, which was contained not in the Missal, but in the Roman Ritual, the liturgical book that contains the rites for the Sacraments.

- They are found only in the Rubrics of the altar Missal (see Note 2), which, unlike hand missals for the laity, is the only authoritative version. It was only in 1965 that Ecce Agnus Dei and the threefold Domine non sum dignus were first incorporated into the text of the Roman Missal. In this Missal, the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar (including the

Confiteor) were made optional, and the Confiteor before Communion was missing, while the priest simply said “Body of Christ” to each of the communicants.

In the Novus Ordo Mass, the Confiteor was reduced to a skeletal form, totally vernacularized, recited communally by priest and people, and made optional among a variety of formulas. The Ecce Agnus Dei contains the abstruse phrase: “Happy are those who are called to His Supper,” and there is no distinction between the Domine non sum dignus of the priest and the laity, as it is recited aloud only once in the New Mass simultaneously by all present. - The expression “the Communion integrates the Sacrifice” refers only to the priest’s Communion: it does not apply to the Communion of the people present at Mass. For, the Sacrifice is integral even if none of the people communicates sacramentally. Council of Trent, Session XXII, Chapter 6; Pius XII, Mediator Dei, 1947, §112: “the integrity of the sacrifice only requires that the priest partake of the heavenly food. Although it is most desirable that the people should also approach the holy table, this is not required for the integrity of the Sacrifice.”

- There is a subtle but significant difference between the Indulgentiam prayers of the Confiteors. At the foot of the altar, the priest asks God for “pardon, absolution and remission of our sins” (peccatorum nostrorum), but before the Communion of the faithful, he prays for the remission of “your sins” (peccatorum vestrorum), i.e., of those about to receive the Sacrament.

- L. Gromier, Lecture given in Paris in 1960, published in ‘La Semaine Sainte Restaurée,’ in Opus Dei, 2, 1962.

- See here.

- ‘Memorandum of His Excellency Mgr., Groeber,’ La Maison-Dieu, 7, 1946, p. 101.

- Pius X, Pascendi, 1907.

- With regard to the Confiteor before Communion, he stated: “since the server says it at the beginning of the Mass in the name of the people, it should not be here repeated.” Pius Parsch, The Liturgy of The Mass, with a Foreword by John J. Glennon, Archbishop of St. Louis, B. Herder Book Co., St Louis, Missouri, 1940, p. 312.

- J. Jungmann rejected the Confiteor before Communion as an “unnecessary” intrusion, claiming that “the Communion of the faithful” is “the natural conclusion of the Mass,” thus implying that it belonged to the nature of the Mass itself which would not be complete without it. J. Jungmann, Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, p. 160.

- At Maria Laach (1951), it was proposed that “when Holy Communion is distributed during Mass, the Confiteor and its following prayers should be omitted” because they are part of “an independent rite for the distribution of Communion outside Mass.” (La Maison-Dieu, n. 37, 1954, p. 131); at Sainte-Odile, France (1952), it was proposed that “the Confiteor, Misereatur and Indulgentiam be omitted before the distribution of Holy Communion during Mass.” (La Maison-Dieu 37, 1954, p. 133); at Lugano (1953), the proposal was “no Confiteor etc., at Communion time.” (H.A. Reinhold, Bringing the Mass to the People, 1960, p. 105); and at Assisi (1956) all the proposals of the previous Liturgical Congresses were subsumed.

- J. Löw, ‘Die Liturgische Reform des Sacrum Triduum,’ Heiliger Dienst, 7, Salzbourg, 1953, p. 91 quoted in La Maison-Dieu, 37, 1954, p. 126.

- Ordo Hebdomadae Sanctae (Order of Holy Week) 1956, Holy Thursday, Chapter II Solemn Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper, § 29

- This so-called “Banquet theory” was espoused by many 20th century liturgists, and is still being promoted in Novus Ordo circles by pastors who mislead the faithful into believing that “the Mass is a Meal.” According to that view, the essence of the Sacrifice lies not in Christ’s self-offering to the Father, but solely in the people’s Communion. In spite of the fact that this false notion was condemned by the Council of Trent (Session 22, Canon 1), it is extremely prevalent in the Church since Vatican II, and finds full expression in the Novus Ordo Mass.

Posted February 15, 2019

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |