Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - LXXVI

Active Participation = Liturgical Abuse

The first thing that strikes us is the inability of liturgical commentators to agree on what “active,” actuosa in Latin, means in the context of lay participation in the liturgy. It is a classic case of the “equivocation fallacy” when multiple meanings of a single term are conflated and treated as if equivalent.

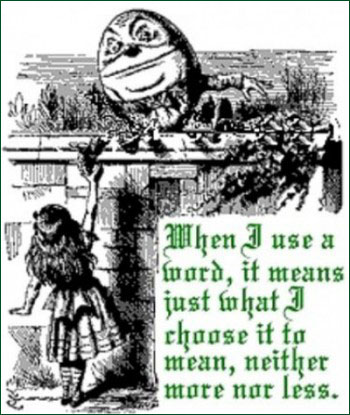

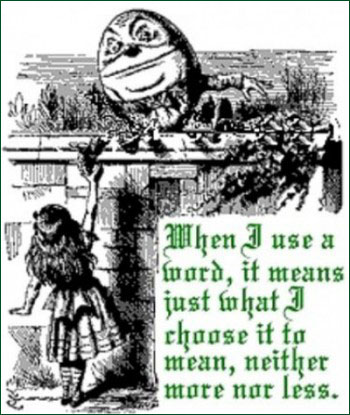

Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass springs to mind, where words mean whatever you choose them to mean, in accordance with the “Humpty Dumpty principle” of (re)definition. (1) This is evidently not the wisest route to follow, for we all know what happened to the eponymous Egg.

Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass springs to mind, where words mean whatever you choose them to mean, in accordance with the “Humpty Dumpty principle” of (re)definition. (1) This is evidently not the wisest route to follow, for we all know what happened to the eponymous Egg.

The progressivists contend that actuosa must be influenced by human values, customs and institutions. In this they are supported by §§37-40 of the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution, which allow the liturgy to incorporate the cultural and social identities of all local communities, including their languages.

But this inescapably turns the decision-making process into a subjective evaluation system, so that no agreed limit can be set on what to include in the liturgy, and no easily identifiable grounds can be found for excluding anything either. (2)

Their more conservative counterparts, however, insist that actuosa means incorporating some traditional customs of genuflecting, making the sign of the Cross etc., with a dash of “dialogue” and congregational singing, plus the odd moment of silence for “contemplation.” The question is: Which of the two sides (if either) is in the right?

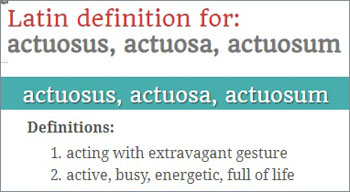

In order to find the true meaning of actuosa – which, as we have seen, Pius X did not use in his 1903 motu proprio – the only reliable method to settle all disputes is to check its etymology. (3) This will show us how we arrived at its present usage, which is the best indicator of what it means today.

In order to find the true meaning of actuosa – which, as we have seen, Pius X did not use in his 1903 motu proprio – the only reliable method to settle all disputes is to check its etymology. (3) This will show us how we arrived at its present usage, which is the best indicator of what it means today.

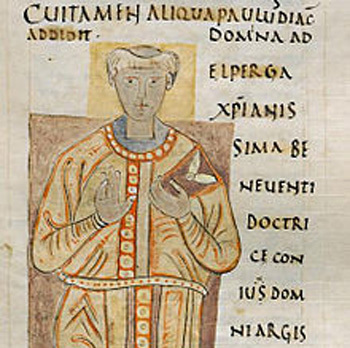

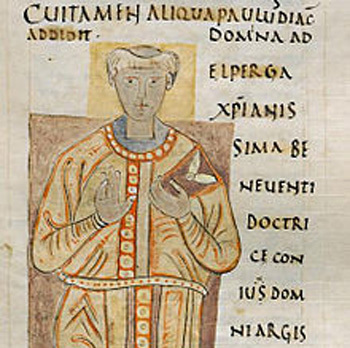

True to form, the Latin word has not changed meaning since its use in classical antiquity. Actuosus – to give it its dictionary entry form – meant the same for Seneca and Cicero as it did for St. Augustine, all of whom used the word to describe vigorous activity involving movement of the body. (4) We know this from the work of the 8th century Benedictine monk, Paul the Deacon, an important member of Charlemagne’s court, who recorded its meaning from Roman times for posterity. (5)

And ever since, all authoritative Latin dictionaries have defined actuosus as “very active, full of activity,” i.e., to a greater degree than other Latin words that denote activity, such as activus and actualis.

But Paul the Deacon had done more than provide a historical record. He put flesh on the bones of the word actuosus, showing how it was used to describe, for example, the actions of “saltatores et histriones” (dancers and actors). (6)

Progressivists 1; Conservatives 0

How ironic, then, that those who have introduced into the liturgy elements of the entertainment world such as clowns, jokes, puppets and dancing girls cavorting round the sanctuary, are in line with the true meaning of “actuosa participatio,” while those who criticize these activities as “abuses” have misunderstood it and are, therefore, mistaken!

Into this category falls the former Cardinal Ratzinger who wrote that “it is totally absurd to try to make the liturgy ‘attractive’ by introducing dancing pantomimes … which frequently … end with applause.” (7) But, on the contrary, that is a logical outcome consistent with the very meaning of actuosa. The real absurdity lies in objecting to such pantomimes while encouraging Vatican II’s call for an “inculturated” liturgy based on “actuosa participatio.”

The Martha-Mary dichotomy

Like it or not, the fact remains that actuosus depicts bodily movements of the most energetic kind, including theatrical performances. In classical Roman literature, as well as in the writings of the Church Fathers, it was always used in direct contrast to otiosus which indicates the state of contemplation. Moreover, it was accepted that one precludes the other.

Nevertheless, there are still some liturgical “experts” desperately trying to square the epistemological circle by maintaining that actuosus means “actual” rather than “active,” while others claim that it means “contemplative.” It is obvious that they are trying to reconcile their bogus claim with the semantic evidence that contradicts it. Yet such evidence is generally suppressed because to admit it would invalidate the very basis of the reform.

Nevertheless, there are still some liturgical “experts” desperately trying to square the epistemological circle by maintaining that actuosus means “actual” rather than “active,” while others claim that it means “contemplative.” It is obvious that they are trying to reconcile their bogus claim with the semantic evidence that contradicts it. Yet such evidence is generally suppressed because to admit it would invalidate the very basis of the reform.

This redefinition of actuosus has, generally speaking, been the position of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI as well as various Heads of the post-Conciliar Congregation for Divine Worship, up to and including Cardinal Sarah. It comes across as an attempt to “sanitize” what they all admitted was problematic for the Church.

However, they stopped short of declaring the reform to have been a terrible mistake. They refuse to accept that the concept of “active participation” is fundamentally flawed, and claim that “abuses” have ruined the principles on which it was originally based. In other words, having set this wild hare running, the Holy See then tries to pretend that it is not responsible for the consequences.

The central paradox

So, they are well and truly stuck in a dilemma of their own making: How can a distinction be made between “active participation” and “liturgical abuse,” when “active participation” itself is the key means by which the “abuses” are actually perpetrated?

This may seem a moot point, a mere hypothesis of no practical importance, until we realize that the reformers have made “active participation” the battle-ground on which another of Vatican II’s slogans ‒ “the common priesthood of the faithful” ‒ is fought.

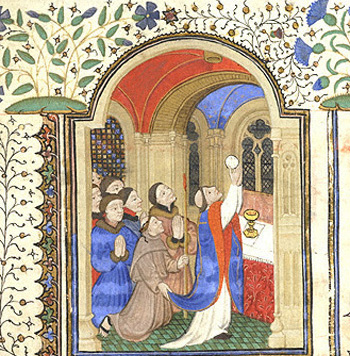

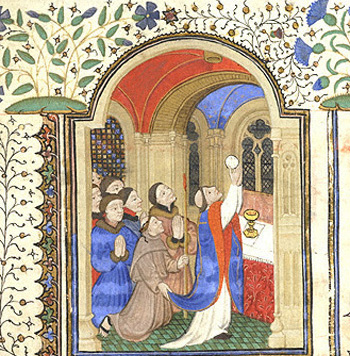

Its rationale was to confer on the congregation the right to perform parts of the Mass that were the purview of the active ministers of the liturgy, i.e., the clergy alone. It follows that, by negating in practice the strict separation that necessarily exists between priests and laity, “active participation” undermines the unique nature of the ordained priesthood.

An impossible conundrum

Wherever the Novus Ordo is celebrated, the confusion caused by the new teachings of Vatican II has left the Church in turmoil. If everything is the wrong way round and upside down, (the priest facing the people, the congregation saying/singing the Mass, lay readers and Eucharistic ministers in the sanctuary, Communion in the hand, the sacred vessels handled by anyone etc.) that is because the Novus Ordo reverses the established order of things, upsetting traditional law and logic, to the detriment of the Faith.

Even the Popes cannot solve the conundrum because they themselves promote the basic premise of the reforms. They pay lip-service to the Church’s teaching that the two “priesthoods” (ordained and lay) are neither synonymous nor on an equal footing. But, they also promote “active participation” in the liturgy, which effectively conflates the two, and even raises the profile of the laity above that of the clergy, in accordance with the reformers’ wishes.

Even the Popes cannot solve the conundrum because they themselves promote the basic premise of the reforms. They pay lip-service to the Church’s teaching that the two “priesthoods” (ordained and lay) are neither synonymous nor on an equal footing. But, they also promote “active participation” in the liturgy, which effectively conflates the two, and even raises the profile of the laity above that of the clergy, in accordance with the reformers’ wishes.

Why this conundrum cannot be solved is because “active participation” is an artificially created catch-phrase that does not reflect Catholic reality, and will, consequently, always be incompatible with it.

The verbal legacy of Communism

Furthermore, the expression “active participation” is an example of the insidious langue de bois (“wooden language)” – the French term for the bureaucratic lingo that was spoken and written by Soviet leaders and functionaries to hide the true meaning of their political systems.

Who would have thought that the type of rhetoric that once served Soviet propaganda, based on Marxist-Leninist values, would be made to serve as a model for ecclesiastical discourse?

Who would have thought that the type of rhetoric that once served Soviet propaganda, based on Marxist-Leninist values, would be made to serve as a model for ecclesiastical discourse?

By ruthlessly imposing “active participation” in every aspect of the liturgy, the reformers have shown themselves capable of perpetrating the same abuse of language and power that has always been associated with totalitarian regimes.

The only way to avoid falling into this liturgical tar pit in the first place is not to adopt the Vatican II wording or its frames of reference. If we wish to avoid such a sticky fate, it would be both practical and prudent, for the good of our souls, to adhere to the Tridentine Rite, which stands unambiguously for Catholic orthodoxy and Tradition.

Continued

Progressivists make the word ‘active’

mean whatever they want

The progressivists contend that actuosa must be influenced by human values, customs and institutions. In this they are supported by §§37-40 of the Vatican II Liturgy Constitution, which allow the liturgy to incorporate the cultural and social identities of all local communities, including their languages.

But this inescapably turns the decision-making process into a subjective evaluation system, so that no agreed limit can be set on what to include in the liturgy, and no easily identifiable grounds can be found for excluding anything either. (2)

Their more conservative counterparts, however, insist that actuosa means incorporating some traditional customs of genuflecting, making the sign of the Cross etc., with a dash of “dialogue” and congregational singing, plus the odd moment of silence for “contemplation.” The question is: Which of the two sides (if either) is in the right?

Latin dictionaries concur with Paul the Deacon on the meaning of the word

True to form, the Latin word has not changed meaning since its use in classical antiquity. Actuosus – to give it its dictionary entry form – meant the same for Seneca and Cicero as it did for St. Augustine, all of whom used the word to describe vigorous activity involving movement of the body. (4) We know this from the work of the 8th century Benedictine monk, Paul the Deacon, an important member of Charlemagne’s court, who recorded its meaning from Roman times for posterity. (5)

And ever since, all authoritative Latin dictionaries have defined actuosus as “very active, full of activity,” i.e., to a greater degree than other Latin words that denote activity, such as activus and actualis.

But Paul the Deacon had done more than provide a historical record. He put flesh on the bones of the word actuosus, showing how it was used to describe, for example, the actions of “saltatores et histriones” (dancers and actors). (6)

Progressivists 1; Conservatives 0

How ironic, then, that those who have introduced into the liturgy elements of the entertainment world such as clowns, jokes, puppets and dancing girls cavorting round the sanctuary, are in line with the true meaning of “actuosa participatio,” while those who criticize these activities as “abuses” have misunderstood it and are, therefore, mistaken!

Into this category falls the former Cardinal Ratzinger who wrote that “it is totally absurd to try to make the liturgy ‘attractive’ by introducing dancing pantomimes … which frequently … end with applause.” (7) But, on the contrary, that is a logical outcome consistent with the very meaning of actuosa. The real absurdity lies in objecting to such pantomimes while encouraging Vatican II’s call for an “inculturated” liturgy based on “actuosa participatio.”

The Martha-Mary dichotomy

Like it or not, the fact remains that actuosus depicts bodily movements of the most energetic kind, including theatrical performances. In classical Roman literature, as well as in the writings of the Church Fathers, it was always used in direct contrast to otiosus which indicates the state of contemplation. Moreover, it was accepted that one precludes the other.

Active participation interpreted here as most vigorous movements of the body...

This redefinition of actuosus has, generally speaking, been the position of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI as well as various Heads of the post-Conciliar Congregation for Divine Worship, up to and including Cardinal Sarah. It comes across as an attempt to “sanitize” what they all admitted was problematic for the Church.

However, they stopped short of declaring the reform to have been a terrible mistake. They refuse to accept that the concept of “active participation” is fundamentally flawed, and claim that “abuses” have ruined the principles on which it was originally based. In other words, having set this wild hare running, the Holy See then tries to pretend that it is not responsible for the consequences.

The central paradox

So, they are well and truly stuck in a dilemma of their own making: How can a distinction be made between “active participation” and “liturgical abuse,” when “active participation” itself is the key means by which the “abuses” are actually perpetrated?

This may seem a moot point, a mere hypothesis of no practical importance, until we realize that the reformers have made “active participation” the battle-ground on which another of Vatican II’s slogans ‒ “the common priesthood of the faithful” ‒ is fought.

Its rationale was to confer on the congregation the right to perform parts of the Mass that were the purview of the active ministers of the liturgy, i.e., the clergy alone. It follows that, by negating in practice the strict separation that necessarily exists between priests and laity, “active participation” undermines the unique nature of the ordained priesthood.

An impossible conundrum

Wherever the Novus Ordo is celebrated, the confusion caused by the new teachings of Vatican II has left the Church in turmoil. If everything is the wrong way round and upside down, (the priest facing the people, the congregation saying/singing the Mass, lay readers and Eucharistic ministers in the sanctuary, Communion in the hand, the sacred vessels handled by anyone etc.) that is because the Novus Ordo reverses the established order of things, upsetting traditional law and logic, to the detriment of the Faith.

A line-up of ministers alongside the priest

on an equal basis

Why this conundrum cannot be solved is because “active participation” is an artificially created catch-phrase that does not reflect Catholic reality, and will, consequently, always be incompatible with it.

The verbal legacy of Communism

Furthermore, the expression “active participation” is an example of the insidious langue de bois (“wooden language)” – the French term for the bureaucratic lingo that was spoken and written by Soviet leaders and functionaries to hide the true meaning of their political systems.

The solution: Remain with the traditional Mass

By ruthlessly imposing “active participation” in every aspect of the liturgy, the reformers have shown themselves capable of perpetrating the same abuse of language and power that has always been associated with totalitarian regimes.

The only way to avoid falling into this liturgical tar pit in the first place is not to adopt the Vatican II wording or its frames of reference. If we wish to avoid such a sticky fate, it would be both practical and prudent, for the good of our souls, to adhere to the Tridentine Rite, which stands unambiguously for Catholic orthodoxy and Tradition.

Continued

- “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean ‒ neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master ‒ that’s all.” - Article 37 states that the Church can admit into the liturgy “anything in these peoples’ way of life which is not indissolubly bound up with superstition and error.” It is left to individual judgement to decide what “indissolubly” entails and which customs are linked to the “spirit of the liturgy” interpreted by reforming liturgists.

But, as Vatican II’s “opening to the world” positively discourages disapproval of secular values, there is precious little scope left for exclusion of “anything in these peoples’ way of life.”

Article 38 indicates that these provisions are not limited to “mission countries” and can apply to any group of people in the world.

Article 40 calls for “an even more radical adaptation of the liturgy” to be implemented where judged suitable by the liturgical reformers. - Etymology, the study of the origin and development of words, comes from the Greek etymos (true). It helps us to understand better the true sense of a word as it is used today.

- They often contrasted it with otiosus, meaning calm, quiet, undisturbed, a state conducive to contemplation.

- Paul the Deacon transcribed and preserved parts of a lexicon written by the Roman grammarian, Festus, as a contribution to Charlemagne’s library. Paul’s summary, Epitome Festi De Verborum Significatu (Epitome of Festus’s “On the meaning of words”), still survives. According to the Festus Project of University College London, “The text, even in its present mutilated state, is an important source for scholars of Roman history.”

Paul’s entry for actuosus is mentioned in the most authoritative of all Latin dictionaries, the Totius Latinitatis Lexicon compiled by the 18th century Italian philologist, Fr. Egidio Forcellini. Forcellini’s Herculean work, conducted over a period of almost 40 years, formed the basis of all similar works that have since been published. - Egidio Forcellini, Totius Latinitatis Lexicon, London, 1828, p. 32.

- Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the Liturgy, San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000, p. 198.

Posted October 9, 2018

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |