Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XCVI

The Rise of an Incredible Anti-Loreto Legend

Now that the translation of the Holy House from Nazareth to its final destination in Loreto has been established on a sound scientific basis, the next question to consider is how it arrived at its destination. There are only two options: by divine intervention (the constant tradition from the 13th century) or by some form of human agency alone (an explanation founded on naturalism that rejects or at least disregards divine intervention).

Post-Reformation anti-Catholic polemics

The expression “flying house,” as used by various religious skeptics, gives the impression that the Loreto tradition was simply a fantasy concocted in the Middle Ages, on a par with tales from Russian folklore or the Arabian Nights, to be believed by people whose grip on reality is tenuous to say the least. From the 16th century, it has become an assumption that the difference between Catholics and Protestants on the matter of miracles is between fantasists and realists.

That is why Dean Stanley called Loreto “the most incredible of Ecclesiastical legends,” (1) and, true to Protestant form, asserted that belief in the miraculous translation of the Holy House of Loreto was the product of “the superstitious craving to win for prayer the favor of consecrated localities.” (2) This broadside against the Catholic Church would be of little interest except that it revealed his preconceived ideas. For Protestantism rejected the existence of specific places such as Loreto, Lourdes, Fatima etc. as the locus of miracles granted through the intercession of Our Lady and the Saints in response to prayers, vows and promises made by the faithful.

That is why Dean Stanley called Loreto “the most incredible of Ecclesiastical legends,” (1) and, true to Protestant form, asserted that belief in the miraculous translation of the Holy House of Loreto was the product of “the superstitious craving to win for prayer the favor of consecrated localities.” (2) This broadside against the Catholic Church would be of little interest except that it revealed his preconceived ideas. For Protestantism rejected the existence of specific places such as Loreto, Lourdes, Fatima etc. as the locus of miracles granted through the intercession of Our Lady and the Saints in response to prayers, vows and promises made by the faithful.

It was also a precept taught by Protestant theologians of the Pseudo-Reformation that miracles had ceased with the last book of the Bible. And so they concluded from this arbitrary principle that any claim by the Catholic Church to authenticate miracles was a “popish” invention designed to deceive the faithful. When applied to the Loreto tradition, Protestantism must conclude that Catholics who believed in the miraculous translation of the Holy House are over-credulous because such an event is literally impossible.

But the argument from incredulity is a logical fallacy of the sort that occurs when we decide that something did not happen, because we cannot personally see how it could happen, on the basis that it does not fit in with our understanding of the world. The fallacy lies in the unwarranted conclusion already contained in the premise. If a state of affairs (the miracle of the Holy House) is impossible to imagine, it does not necessarily follow that it is false; it may only mean that our human imagination is limited. This is especially true in the domain of divine intervention in the natural world.

But the argument from incredulity is a logical fallacy of the sort that occurs when we decide that something did not happen, because we cannot personally see how it could happen, on the basis that it does not fit in with our understanding of the world. The fallacy lies in the unwarranted conclusion already contained in the premise. If a state of affairs (the miracle of the Holy House) is impossible to imagine, it does not necessarily follow that it is false; it may only mean that our human imagination is limited. This is especially true in the domain of divine intervention in the natural world.

Regarding the negative reactions to papal approved miracles founded on Tradition, we have seen how some people, for whom a miraculous intervention is the object of constant scorn, will instinctively reject miracles simply because they have an ideological preconception, an a priori position or bias against them. To the skeptic in this area, a fitting rejoinder would be Hamlet’s statement: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophies.”

Under the influence of Progressivism in the Church, the official position on the Translation of the Holy House began to change from the mid-20th century to downplay any supernatural explanation. This was, incidentally, one of the reasons why – inexplicably from a Catholic point of view – the Feast of Our Lady of Loreto was suppressed in 1960.

Fr. Giuseppe Santarelli, OFM, the Director of the Universal Congregation of the Holy House, is now regarded, through his voluminous writings, as the single most authoritative voice on the Holy House. The only problem is that he does not believe in the supernatural nature of its translation. While he accepted without question the scientific evidence that the materials of the Holy House were from Nazareth, when it came to the manner of their conveyance to Loreto, he baulked at the idea of a miraculous transportation.

Fr. Giuseppe Santarelli, OFM, the Director of the Universal Congregation of the Holy House, is now regarded, through his voluminous writings, as the single most authoritative voice on the Holy House. The only problem is that he does not believe in the supernatural nature of its translation. While he accepted without question the scientific evidence that the materials of the Holy House were from Nazareth, when it came to the manner of their conveyance to Loreto, he baulked at the idea of a miraculous transportation.

Departing from the 800-year-old tradition endorsed by successive Popes that the Holy House was borne by Angels to its final resting place in Loreto, he promoted a more mundane explanation. But when we examine the “proofs” for these non-miraculous claims, we will find that they are not only inconclusive but also require considerably more faith (of the blind variety) to accept them than the entirely reasonable tradition of angelic transportation.

The 'Angeli' hypothesis

The story goes that a noble Byzantine family called Angeli – or Angeloi in Greek – (meaning “angels”), wishing to save the Holy House in Nazareth from destruction by Muslim forces, dismantled the entire edifice stone by stone and transported it by land and sea to Loreto where it was rebuilt on the present spot. Fr. Santarelli uses the coincidence of the word “angels” for the family name and the celestial beings to suggest that the Loreto tradition was simply the result of a linguistic muddle: In the course of time, pious Catholics substituted heavenly Angels for the Angeli of Constantinople as the conveyors of the Holy House. (3)

But not everyone is satisfied with this glib explanation, and for good reason, as we shall see below.

The only documentary source that has been used to support all this is a copy of the long lost Chartularium Culisanense, a collection of documents named after the town of Collesano in Sicily where it was once kept in the palace of a family named De Angelis. The original documents were lost, but an unauthenticated copy of a copy is declared to exist, and was published for the first time in 1985.

Some documents of the Chartularium have recently been challenged by historians as forgeries, (4) and the issue of their authenticity continues to be the subject of scholarly debate. The balance of probability is in favor of the spuriousness of at least some of the documents, including Folio 181, which is relevant to the Holy House. But whether this particular document was genuine or not, the point is that it does not provide any convincing evidence to support the hypothesis that the Holy House was transported from Nazareth to Loreto by human agency.

Folio 181 of the Chartularium gives details of a marriage dowry of 1294 (the year when the Holy House came to Italy) containing, among other things, “Sanctas petras ex domo Dominae Nostrae Deiparae Virginis ablatas” (holy stones taken away from the house of Our Lady the Virgin Mother of God) in Nazareth. The occasion was the marriage between Philip of Anjou, son of the King of Naples, to

Thamar (Margherita) daughter of Nicephorus I Comnenus Ducas, despot of Epirus.

Folio 181 of the Chartularium gives details of a marriage dowry of 1294 (the year when the Holy House came to Italy) containing, among other things, “Sanctas petras ex domo Dominae Nostrae Deiparae Virginis ablatas” (holy stones taken away from the house of Our Lady the Virgin Mother of God) in Nazareth. The occasion was the marriage between Philip of Anjou, son of the King of Naples, to

Thamar (Margherita) daughter of Nicephorus I Comnenus Ducas, despot of Epirus.

The bride’s father was a descendant of the Byzantine Angeli Dynasty and, it was claimed, financed the whole operation of demolishing the Holy House in Nazareth, including the cost of transporting the stones to Italy by means of Crusaders returning from the Holy Land, plus their storage in an unknown place in Italy until they were put together again in Loreto.

This story, based on documents of dubious authenticity, negates the carefully witnessed chronicle of the Holy House in its various stopping places in Dalmatia and Italy. It leaves unaddressed the absurd conclusion that the House would have had to be demolished and rebuilt four times in quick succession during its odyssey.

Nor can anyone explain how the House was rebuilt in Loreto, without foundations, in the middle of a road, against the laws of Recanati, with the same physical and chemical composition of mortar used in the first century. And all this without anyone noticing or commenting,

Surely the herculean task of transporting several tons of masonry on a hazardous 3,000-km journey by land and sea in the 13th century would have had its chroniclers, eager to relay the happy news of the rescue of the Nazareth House from imminent destruction by Muslim forces. Such an undertaking would certainly have been promoted in the literature of the time as something of a miracle in itself without the need to involve Angels.

But some Catholics today, including Fr. Santarelli, the Church’s spokesman on all things Loretan, find the recently proposed narrative of the translation of the Holy House more credible than the age-old tradition of Loreto.

In the next article, we will deal with other aspects of the anti-Loreto legend: the alleged sighting of documents in the Vatican archives purporting to show that the Angeli family paid for the shipping of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto, and the discovery of coins in the subsoil of the house, supposedly marking the date when it was “rebuilt.”

Continued

Post-Reformation anti-Catholic polemics

The expression “flying house,” as used by various religious skeptics, gives the impression that the Loreto tradition was simply a fantasy concocted in the Middle Ages, on a par with tales from Russian folklore or the Arabian Nights, to be believed by people whose grip on reality is tenuous to say the least. From the 16th century, it has become an assumption that the difference between Catholics and Protestants on the matter of miracles is between fantasists and realists.

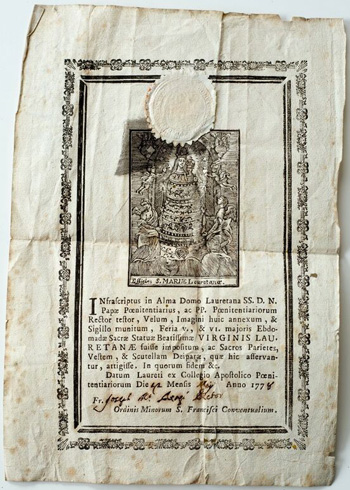

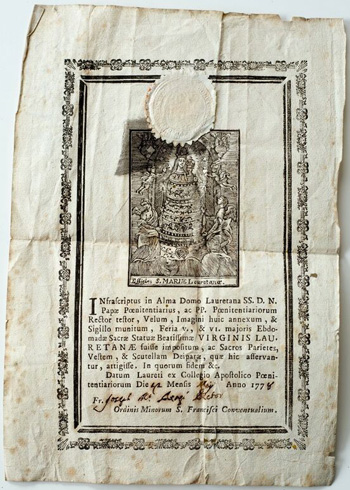

Basilica of Loreto built to protect the Holy House

It was also a precept taught by Protestant theologians of the Pseudo-Reformation that miracles had ceased with the last book of the Bible. And so they concluded from this arbitrary principle that any claim by the Catholic Church to authenticate miracles was a “popish” invention designed to deceive the faithful. When applied to the Loreto tradition, Protestantism must conclude that Catholics who believed in the miraculous translation of the Holy House are over-credulous because such an event is literally impossible.

A document dated 1778 authenticating a relic touched to the walls of the Holy House

Regarding the negative reactions to papal approved miracles founded on Tradition, we have seen how some people, for whom a miraculous intervention is the object of constant scorn, will instinctively reject miracles simply because they have an ideological preconception, an a priori position or bias against them. To the skeptic in this area, a fitting rejoinder would be Hamlet’s statement: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophies.”

Under the influence of Progressivism in the Church, the official position on the Translation of the Holy House began to change from the mid-20th century to downplay any supernatural explanation. This was, incidentally, one of the reasons why – inexplicably from a Catholic point of view – the Feast of Our Lady of Loreto was suppressed in 1960.

Fr. Giuseppe Santarelli

Departing from the 800-year-old tradition endorsed by successive Popes that the Holy House was borne by Angels to its final resting place in Loreto, he promoted a more mundane explanation. But when we examine the “proofs” for these non-miraculous claims, we will find that they are not only inconclusive but also require considerably more faith (of the blind variety) to accept them than the entirely reasonable tradition of angelic transportation.

The 'Angeli' hypothesis

The story goes that a noble Byzantine family called Angeli – or Angeloi in Greek – (meaning “angels”), wishing to save the Holy House in Nazareth from destruction by Muslim forces, dismantled the entire edifice stone by stone and transported it by land and sea to Loreto where it was rebuilt on the present spot. Fr. Santarelli uses the coincidence of the word “angels” for the family name and the celestial beings to suggest that the Loreto tradition was simply the result of a linguistic muddle: In the course of time, pious Catholics substituted heavenly Angels for the Angeli of Constantinople as the conveyors of the Holy House. (3)

But not everyone is satisfied with this glib explanation, and for good reason, as we shall see below.

The only documentary source that has been used to support all this is a copy of the long lost Chartularium Culisanense, a collection of documents named after the town of Collesano in Sicily where it was once kept in the palace of a family named De Angelis. The original documents were lost, but an unauthenticated copy of a copy is declared to exist, and was published for the first time in 1985.

Some documents of the Chartularium have recently been challenged by historians as forgeries, (4) and the issue of their authenticity continues to be the subject of scholarly debate. The balance of probability is in favor of the spuriousness of at least some of the documents, including Folio 181, which is relevant to the Holy House. But whether this particular document was genuine or not, the point is that it does not provide any convincing evidence to support the hypothesis that the Holy House was transported from Nazareth to Loreto by human agency.

Nicephorus I Comnenus Ducas

The bride’s father was a descendant of the Byzantine Angeli Dynasty and, it was claimed, financed the whole operation of demolishing the Holy House in Nazareth, including the cost of transporting the stones to Italy by means of Crusaders returning from the Holy Land, plus their storage in an unknown place in Italy until they were put together again in Loreto.

This story, based on documents of dubious authenticity, negates the carefully witnessed chronicle of the Holy House in its various stopping places in Dalmatia and Italy. It leaves unaddressed the absurd conclusion that the House would have had to be demolished and rebuilt four times in quick succession during its odyssey.

Nor can anyone explain how the House was rebuilt in Loreto, without foundations, in the middle of a road, against the laws of Recanati, with the same physical and chemical composition of mortar used in the first century. And all this without anyone noticing or commenting,

Surely the herculean task of transporting several tons of masonry on a hazardous 3,000-km journey by land and sea in the 13th century would have had its chroniclers, eager to relay the happy news of the rescue of the Nazareth House from imminent destruction by Muslim forces. Such an undertaking would certainly have been promoted in the literature of the time as something of a miracle in itself without the need to involve Angels.

But some Catholics today, including Fr. Santarelli, the Church’s spokesman on all things Loretan, find the recently proposed narrative of the translation of the Holy House more credible than the age-old tradition of Loreto.

In the next article, we will deal with other aspects of the anti-Loreto legend: the alleged sighting of documents in the Vatican archives purporting to show that the Angeli family paid for the shipping of the Holy House from Nazareth to Loreto, and the discovery of coins in the subsoil of the house, supposedly marking the date when it was “rebuilt.”

Continued

- A. P. Stanley, Sinai and Palestine, p. 448.

- Ibid., p. 443.

- G. Santarelli, Loreto: L’altra metà di Nazaret: la storia, il mistero e l’arte della santa Casa, Milan: Ed. Terra Santa, 2016, p. 39.

- Andrea Nicolotti, ‘Su alcune testimonianze del Chartularium Culisanense, sulle false origini dell’Ordine Costantiniano Angelico di Santa Sofia e su taluni suoi documenti conservati presso l’Archivio di Stato di Napoli,’ (On some testimonies of the Chartularium Culisanense, on the fake origins of the Angelic Constantinian Order of St. Sophia and on certain of its documents kept at the State Archives of Naples), Giornale di Storia, vol. 8, 2012, pp. 1-18.

Posted August 5, 2020

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |