About the Church

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Authority of Pontifical & Conciliar Documents – II

What Is an Ex Cathedra Papal Pronouncement?

In the last article the different types of magisterium were set out. Now, let us first consider the Extraordinary Papal Magisterium.

From his catechism lessons, every Catholic remembers that the Pope is infallible when speaking ex cathedra and in matters of Faith and Morals. A true formula, however its extreme brevity – inevitable, incidentally – can lead to misunderstanding, and for this reason it requires some explanations.

In fact, what does ex cathedra mean? Is speaking from St. Peter's Chair the same as teaching officially? Is it when the Pope addresses the Universal Church? Are the Encyclicals, for example, being official documents and generally addressed to the whole Church, ipso facto ex cathedra pronouncements?

In fact, what does ex cathedra mean? Is speaking from St. Peter's Chair the same as teaching officially? Is it when the Pope addresses the Universal Church? Are the Encyclicals, for example, being official documents and generally addressed to the whole Church, ipso facto ex cathedra pronouncements?

In the definition of pontifical infallibility made at Vatican Council I, we find a comprehensive solution for such doubts. The Constitution Pastor Aeternus establishes the necessary conditions for the infallibility of papal definitions.

It teaches that the Pope is infallible “when speaking ex cathedra, that is, when, in the exercise of his office as Doctor and Pastor of all Christians, by virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning matters of Faith and Morals that must be held by the whole Church.“ (Denzinger, Enchiridion Symbolorum, n. 1839)

Theologians are unanimous in seeing in this text the solution for problems regarding the conditions of pontifical infallibility. (1)

There are four conditions, therefore, for there to be a pronouncement of the Extraordinary Papal Magisterium:

Infallibility is a faculty that resides in the person of the Pontiff, who is a being endowed with intelligence and a will. He will or will not use that power, as he wishes.

In his private life, e.g. in a conversation with friends or a letter to a relative, it is clear that the Pope is not using his defining power. Hence

the first condition: he must speak as a universal Master.

In his private life, e.g. in a conversation with friends or a letter to a relative, it is clear that the Pope is not using his defining power. Hence

the first condition: he must speak as a universal Master.

In more than one document Pope Benedict XIV states that he does not issue this or that theological opinion as Supreme Pontiff, but as a simple private doctor. Pope St. Pius X affirmed the same about statements he made in private audiences. (2)

But for infallibility to be present, it is not enough for the Pope to teach as a universal Master. Indeed, a second condition must be fulfilled: He must speak in the use of the fullness of his powers. Such is the importance and gravity of an infallible pronouncement, that it must be made quite clear that, in issuing such a statement, the Supreme Pontiff is using the fullness of his prerogatives as legitimate successor of St. Peter.

This is why both Pope Pius IX in the definition of the Immaculate Conception (Ineffabilis Deus, 1854) and Pope Pius XII in defining the Assumption of Our Lady (Munificentissimus Deus, 1950) state that they speak “with the authority of Our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul and by our own.”

This is still not enough. Even as universal Teacher and in the exercise of all his authority, the Pope can limit himself: e.g. by recommending a doctrine, ordering that it be taught in seminaries or warning the faithful of the danger that exists in denying it. That is why there is a third condition: the manifestation of the desire to define.

This is still not enough. Even as universal Teacher and in the exercise of all his authority, the Pope can limit himself: e.g. by recommending a doctrine, ordering that it be taught in seminaries or warning the faithful of the danger that exists in denying it. That is why there is a third condition: the manifestation of the desire to define.

This desire to define is lacking, for example, in those documents – despite how wise, positive and energetic they may be – in which the Popes have recommended or even imposed the study and teaching of Thomism on the teachers of philosophy and sacred theology. These would include, among others, Pope Leo XIII's Encyclical Aeterni Patris; Pope St. Pius X's Motu proprio Doctoris Angelici and Pope Pius XI's Encyclical Studiorum Ducem.

The last condition is that it must be a matter that concerning Faith or Morals. We leave this item aside here because it would expand the study of the primary and secondary objects of infallibility beyond the limits of this series. (3)

The intention to define is crucial

The crux of the matter lies in the third condition: He must manifest his intention to define.

How does such an intention manifest itself? Is it by using the word “we define”? Is it by the excommunication of those who say otherwise? Is it by the legal nature of the document?

How does such an intention manifest itself? Is it by using the word “we define”? Is it by the excommunication of those who say otherwise? Is it by the legal nature of the document?

None of these signs is apodictic. (4) The fundamental point is that it be clear, by whatever way he chooses, that the Pope wants to define a dogma.

Thus, in solemn definitions, the Supreme Pontiffs use multiple terms to render their intention unquestionable: “We promulgate, we decree, we define, we declare, we proclaim,” etc.

In other cases, such verbs will be missing, but the circumstances surrounding the document will show that there was a willingness to define. This is what happens when the Pope imposes the whole Church to accept a formula of Faith, or when he officially and definitively resolves a doctrinal dispute between Bishops in a document addressed, at least indirectly, to the Universal Church.

Continued

From his catechism lessons, every Catholic remembers that the Pope is infallible when speaking ex cathedra and in matters of Faith and Morals. A true formula, however its extreme brevity – inevitable, incidentally – can lead to misunderstanding, and for this reason it requires some explanations.

A window at Saint Melaine Church

shows the Pope speaking ex cathedra

In the definition of pontifical infallibility made at Vatican Council I, we find a comprehensive solution for such doubts. The Constitution Pastor Aeternus establishes the necessary conditions for the infallibility of papal definitions.

It teaches that the Pope is infallible “when speaking ex cathedra, that is, when, in the exercise of his office as Doctor and Pastor of all Christians, by virtue of his supreme apostolic authority, he defines a doctrine concerning matters of Faith and Morals that must be held by the whole Church.“ (Denzinger, Enchiridion Symbolorum, n. 1839)

Theologians are unanimous in seeing in this text the solution for problems regarding the conditions of pontifical infallibility. (1)

There are four conditions, therefore, for there to be a pronouncement of the Extraordinary Papal Magisterium:

- The Pope must speak as the universal Doctor and Pastor;

- He must use the fullness of his apostolic authority;

- He must express the desire to define;

- He must be dealing with a matter of Faith or Morals.

Infallibility is a faculty that resides in the person of the Pontiff, who is a being endowed with intelligence and a will. He will or will not use that power, as he wishes.

Francis speaking on climate change in Peru: not an infallible teaching but just his opinion

In more than one document Pope Benedict XIV states that he does not issue this or that theological opinion as Supreme Pontiff, but as a simple private doctor. Pope St. Pius X affirmed the same about statements he made in private audiences. (2)

But for infallibility to be present, it is not enough for the Pope to teach as a universal Master. Indeed, a second condition must be fulfilled: He must speak in the use of the fullness of his powers. Such is the importance and gravity of an infallible pronouncement, that it must be made quite clear that, in issuing such a statement, the Supreme Pontiff is using the fullness of his prerogatives as legitimate successor of St. Peter.

This is why both Pope Pius IX in the definition of the Immaculate Conception (Ineffabilis Deus, 1854) and Pope Pius XII in defining the Assumption of Our Lady (Munificentissimus Deus, 1950) state that they speak “with the authority of Our Lord Jesus Christ, of the Blessed Apostles St. Peter and St. Paul and by our own.”

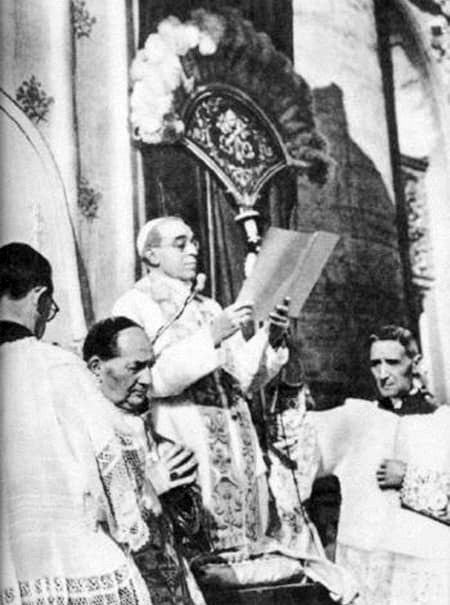

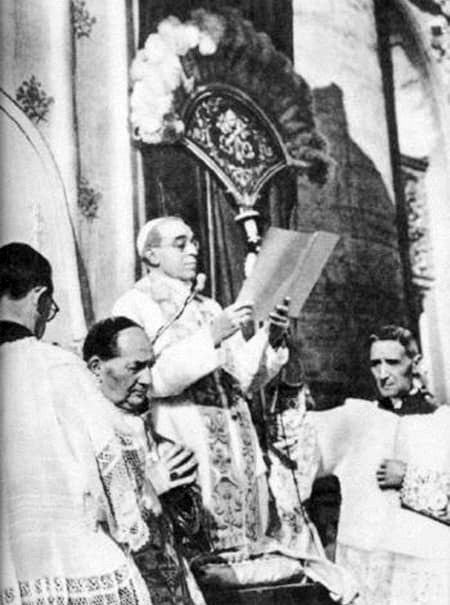

Pope Pius XII infallibly pronounces the dogma of the Assumption of Our Lady

This desire to define is lacking, for example, in those documents – despite how wise, positive and energetic they may be – in which the Popes have recommended or even imposed the study and teaching of Thomism on the teachers of philosophy and sacred theology. These would include, among others, Pope Leo XIII's Encyclical Aeterni Patris; Pope St. Pius X's Motu proprio Doctoris Angelici and Pope Pius XI's Encyclical Studiorum Ducem.

The last condition is that it must be a matter that concerning Faith or Morals. We leave this item aside here because it would expand the study of the primary and secondary objects of infallibility beyond the limits of this series. (3)

The intention to define is crucial

The crux of the matter lies in the third condition: He must manifest his intention to define.

Benedict signs his Encyclical Spes Salvi; like his other encylicals, not an infallbile teaching

None of these signs is apodictic. (4) The fundamental point is that it be clear, by whatever way he chooses, that the Pope wants to define a dogma.

Thus, in solemn definitions, the Supreme Pontiffs use multiple terms to render their intention unquestionable: “We promulgate, we decree, we define, we declare, we proclaim,” etc.

In other cases, such verbs will be missing, but the circumstances surrounding the document will show that there was a willingness to define. This is what happens when the Pope imposes the whole Church to accept a formula of Faith, or when he officially and definitively resolves a doctrinal dispute between Bishops in a document addressed, at least indirectly, to the Universal Church.

Continued

- See Reanciscus Diekamp, Theologiae Dogmaticae Manuale, Parisiis-Tornaci-Romae: Desclée, 1933, vol. I, p. 71; Ludovicus Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, Prati: Giachetti, 1909, vol. 1, p. 639 ff; Lucien Choupin, Valeur des Décisions Doctrinales et Disciplinaires du Saint-Siège, Paris: Beauchesne, 1928, p. 6; Hervé, p. 473 ff; Charles Journet, L'Eglise du Verbe Incarné, Fribourg: Desclée, 1962, vol 1, p. 569; Paul Nau, "El magisterio pontificio ordinario, lugar teológico," in Verbo, Madrid, n. 14, p. 43; Ioachim Salaverri, "De Ecclesia Christi," in Sacrae Theologiae Summa, Matrid: B.A.C., 1958, vol. I, p. 697; Sisto Cartechini, "Dall'Opinione al Domma," in La Civiltà Cattolica, Roma, 1953, p. 40.

- Cf. Nau, "El Magisterio," p. 48, note 35.

- Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, vol. I, pp. 392 ff; Lucien Choupin, Valeur des Décisions Doctrinales et Disciplinaires, pp. 38 ff; J. M. Hervé, Manuale Theologiae Dogmaticae, Parisiis: Berche, 1952, vol. I, pp. 496 ff; Ioachim Salaverri, "De Ecclesia Christi," vol. I, pp. 729 ff.

- Cf. Cartechini, "Dall'Opinione al Domma," pp. 29, 31, 36, 54.

First published in Catolicísmo, n.. 202, October 1967

Posted September 13, 2019

Posted September 13, 2019