Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXV

The Role of Josef Jungmann

in the Liturgical Reform

Another fault line in Pope Pius XII’s Assisi Address that was poised to release enough pressure for an earthquake (or should that be a Churchquake?) was the confidence he placed in the historical-critical studies carried out by contemporary liturgical experts. He expressed the hope that these would “bring forth a rich harvest, to the benefit of the individual members as well as the Church as a whole.”

But, how realistic was this hope considering that the experts in question – international scholars of a progressivist bent – were none other than the promoters of the Liturgical Movement led by Bugnini?

Evidence of collusion

Fr. Frederick McManus noted that Pius XII’s “1948 Commission was influenced in succeeding years by the meetings of (mostly) European scholars … with which Antonelli, Löw and Bugnini were in contact.”(1)

Fr. Frederick McManus noted that Pius XII’s “1948 Commission was influenced in succeeding years by the meetings of (mostly) European scholars … with which Antonelli, Löw and Bugnini were in contact.”(1)

By far the most influential of these was Josef Jungmann, SJ, a Professor of “Pastoral Theology” at the University of Innsbruck and a Consulter to the 1948 Liturgical Commission. (2) (Bugnini later publicly endorsed Jungmann’s theory of the Pastoral Nature of the Liturgy). (3)

These were the men who colluded in secret to produce the revised Holy Week rites and other liturgical changes that were imposed on the Church in the 1950s. In fact, some of them were participants at the Assisi Congress, basking in the warmth of the Pope’s praise.

Jungmann would eventually play a major role in the drafting and implementation of Vatican II’s Constitution on the Liturgy and, also, in the fabrication of the Novus Ordo.

Jungmann: a liturgical giant with feet of clay

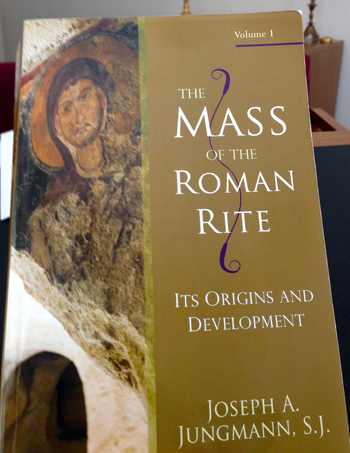

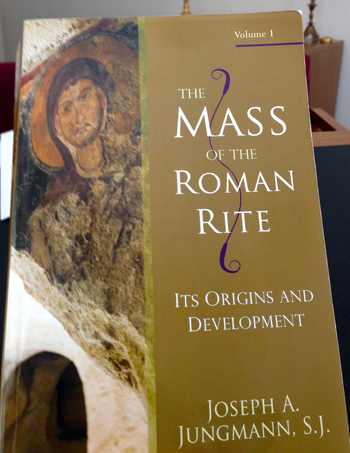

Josef Jungmann published his magnum opus on the history of the Roman Rite, Missarum Sollemnia, in 1948, (4) (see here) which was long hailed as a classic of liturgical scholarship and became the ultimate reference and definitive resource book for the Liturgical Movement.

His contemporaries conferred on him god-like status: his fellow-Jesuit, Fr. Clifford Howell, credited him with near “omniscience.”(5) Fr. Louis Bouyer rhapsodized that his book was “the greatest scholarly work of our times on the history of the Roman Mass,” (6) and Cardinal Ratzinger called him “one of the truly great liturgists of our time.” (7)

His contemporaries conferred on him god-like status: his fellow-Jesuit, Fr. Clifford Howell, credited him with near “omniscience.”(5) Fr. Louis Bouyer rhapsodized that his book was “the greatest scholarly work of our times on the history of the Roman Mass,” (6) and Cardinal Ratzinger called him “one of the truly great liturgists of our time.” (7)

But, it turned out that Jungmann was ascribed authoritative status not through excellence in research integrity, but largely because he upheld the progressivist ideas of the liturgical establishment. It is now known that he “mined” the field of early Christian liturgies to produce data that supported his “antiquarian” agenda.

More recent scholarly research (8) has shown conclusively that Jungmann’s work was riddled with erroneous assumptions about the early Christian liturgies: he often hypothesized about events that he would like to have happened – for instance Mass celebrated versus populum (facing the people), an Offertory procession, bidding prayers at all Masses – thereby assuming tacitly that they did. And he did not scruple to skew the evidence in favor of his own preconceptions. One could say that, in some areas, Jungmann raised the falsification of data to an art form.

It was only later that he came to realize his error about versus populum liturgies. But, he said this orientation should nevertheless be adopted for “pastoral” purposes, thus laying bare the real reason for undertaking his research in the first place. Unfortunately, Pius XII, via Bugnini, relied on Jungmann’s compromised research for the Holy Week reforms and decided that some key aspects of it could be imported into the liturgy at the stroke of the Supreme Legislator’s pen.

Not so much a fact-finding mission as a fault-finding one

While many of his fellow priests were suffering and dying for the Faith in war-torn Europe, Jungmann spent most of WW2 comfortably ensconced in a convent in the Austrian countryside, (9) which he used as the perfect hide-away in which to research for and write his history of the Mass. There, like a captious pedant, he busied himself finding fault with almost every aspect of the Roman Rite as it had been celebrated over the previous 1500 years.

While many of his fellow priests were suffering and dying for the Faith in war-torn Europe, Jungmann spent most of WW2 comfortably ensconced in a convent in the Austrian countryside, (9) which he used as the perfect hide-away in which to research for and write his history of the Mass. There, like a captious pedant, he busied himself finding fault with almost every aspect of the Roman Rite as it had been celebrated over the previous 1500 years.

It is interesting to note that while the Nazis were persecuting the Catholic Church in his native Austria, Jungmann, in the safety of his “funk hole,” (10) was jack-booting his way through the history of the Roman Mass. So brutal were his attacks that one could say that he kicked it around and finally kicked it to pieces. When there was nothing left to criticize, he arbitrarily concluded that any prayers of the Mass used after the early centuries of the Church “would really all have to vanish.” (11)

The following are just a few examples of his criticisms:

Modernism re-enters the Church under Pius XII

To those liturgists present at the Assisi Congress who included Jungmann among their number, Pius XII said in his Address that it was “a consolation and a joy for us to know that we can rely on your help and your understanding in these matters.” But the aim of the Liturgical Movement was to restructure the Mass so that it would no longer reflect essential Catholic doctrine, an aim that would be eventually realized in the creation of the Novus Ordo.

Thus, he trusted “men with itching ears” (2 Tim 4:3) with the reform of the liturgy, men whose theology represented the “striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass as it was formulated in session XXII of the Council of Trent,” mentioned later by Cardinal Ottaviani with reference to the Novus Ordo.

Thus, he trusted “men with itching ears” (2 Tim 4:3) with the reform of the liturgy, men whose theology represented the “striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass as it was formulated in session XXII of the Council of Trent,” mentioned later by Cardinal Ottaviani with reference to the Novus Ordo.

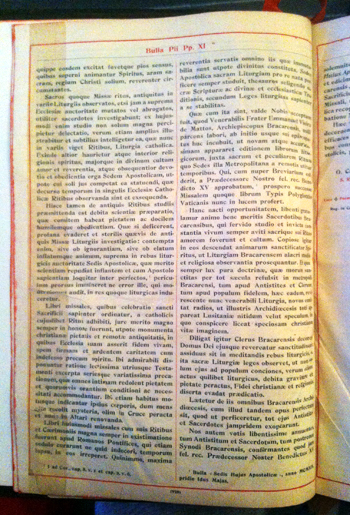

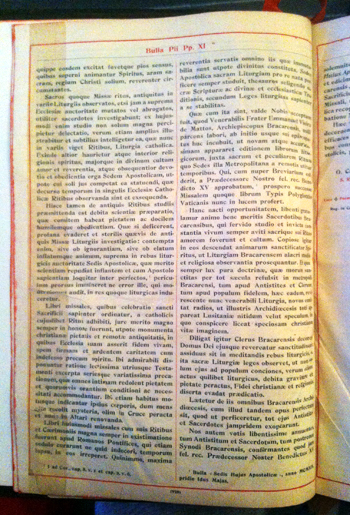

In 1924, Pius XI had warned about the dangers of blind reliance on “expert” testimony based on shoddy historical scholarship and neo-modernist ideas:

“However, in these studies concerning ancient Rites the necessary groundwork for knowledge must first be undertaken in a spirit of piety and docile and humble obedience. And if these are lacking, any research whatever into ancient liturgies of Mass will turn out to be irreverent and fruitless: for when, either through ignorance or a proud and conceited mind, the supreme authority of the Apostolic See in liturgical matters, which rightly rejects puffed-up knowledge, and, with the Apostle, ‘speaks wisdom among the perfect’ (1 Cor. 8: 1,2: 6), has been scorned, there immediately looms the danger that the error known as Modernism will be introduced also into liturgical matters.” (18)

In fact, a resurgent Modernism had gained such a foothold in Pius XII’s time that even a Protestant theologian, cheering on the progress of the Liturgical Movement from the sidelines, noted in 1954 that “It is especially in its theological method that the Liturgical Movement evidences a relationship with the errors of Modernism as condemned by Pius X in Pascendi … certain of the most fruitful trends condemned by Pius X in his blanket condemnation have served to make the Liturgical Movement the great power it is today.” (19)

Continued

But, how realistic was this hope considering that the experts in question – international scholars of a progressivist bent – were none other than the promoters of the Liturgical Movement led by Bugnini?

Evidence of collusion

Fr. Josef Jungmann, the ‘man of the hour’ in the Liturgical Reform

By far the most influential of these was Josef Jungmann, SJ, a Professor of “Pastoral Theology” at the University of Innsbruck and a Consulter to the 1948 Liturgical Commission. (2) (Bugnini later publicly endorsed Jungmann’s theory of the Pastoral Nature of the Liturgy). (3)

These were the men who colluded in secret to produce the revised Holy Week rites and other liturgical changes that were imposed on the Church in the 1950s. In fact, some of them were participants at the Assisi Congress, basking in the warmth of the Pope’s praise.

Jungmann would eventually play a major role in the drafting and implementation of Vatican II’s Constitution on the Liturgy and, also, in the fabrication of the Novus Ordo.

Jungmann: a liturgical giant with feet of clay

Josef Jungmann published his magnum opus on the history of the Roman Rite, Missarum Sollemnia, in 1948, (4) (see here) which was long hailed as a classic of liturgical scholarship and became the ultimate reference and definitive resource book for the Liturgical Movement.

Jungmann's 2-volume American edition ushered in the New Mass

But, it turned out that Jungmann was ascribed authoritative status not through excellence in research integrity, but largely because he upheld the progressivist ideas of the liturgical establishment. It is now known that he “mined” the field of early Christian liturgies to produce data that supported his “antiquarian” agenda.

More recent scholarly research (8) has shown conclusively that Jungmann’s work was riddled with erroneous assumptions about the early Christian liturgies: he often hypothesized about events that he would like to have happened – for instance Mass celebrated versus populum (facing the people), an Offertory procession, bidding prayers at all Masses – thereby assuming tacitly that they did. And he did not scruple to skew the evidence in favor of his own preconceptions. One could say that, in some areas, Jungmann raised the falsification of data to an art form.

It was only later that he came to realize his error about versus populum liturgies. But, he said this orientation should nevertheless be adopted for “pastoral” purposes, thus laying bare the real reason for undertaking his research in the first place. Unfortunately, Pius XII, via Bugnini, relied on Jungmann’s compromised research for the Holy Week reforms and decided that some key aspects of it could be imported into the liturgy at the stroke of the Supreme Legislator’s pen.

Not so much a fact-finding mission as a fault-finding one

Jungman: ‘The priest does not take the place of Christ at Mass, but is a server of the community’

It is interesting to note that while the Nazis were persecuting the Catholic Church in his native Austria, Jungmann, in the safety of his “funk hole,” (10) was jack-booting his way through the history of the Roman Mass. So brutal were his attacks that one could say that he kicked it around and finally kicked it to pieces. When there was nothing left to criticize, he arbitrarily concluded that any prayers of the Mass used after the early centuries of the Church “would really all have to vanish.” (11)

The following are just a few examples of his criticisms:

- “The sacrifice of the Mass is not the sacrifice for the redemption of the world, but the sacrifice made by the redeemed.” (12)

- He questioned the authenticity of the words Mysterium Fidei in the consecratory formula of the wine, regarding them as an extraneous element, an unscriptural “intrusion” with no connection to transubstantiation. (13)

- He insinuated that the Catholic doctrine of the priest performing the sacrifice as an alter Christus was a later historical invention and was, therefore, by implication, a false teaching. (14)

- He accused priests of usurping the role of the laity, creating a gap between the clergy and the people and preventing the latter from participating in the liturgy. (15)

- He presented a paper at the Assisi Congress in which he placed the principal emphasis of the Mass on the “community meal aspect” and the “gathering of the People of God,” described the Mass as primarily a service of thanksgiving by the assembled community, disparaged the silent recitation of the Canon as a barrier to participation, and stated that the Mass should be in the vernacular “so that the people can speak and sing together.” (here) (16)

Modernism re-enters the Church under Pius XII

To those liturgists present at the Assisi Congress who included Jungmann among their number, Pius XII said in his Address that it was “a consolation and a joy for us to know that we can rely on your help and your understanding in these matters.” But the aim of the Liturgical Movement was to restructure the Mass so that it would no longer reflect essential Catholic doctrine, an aim that would be eventually realized in the creation of the Novus Ordo.

Pius XI’s warning in Inter multiplices

In 1924, Pius XI had warned about the dangers of blind reliance on “expert” testimony based on shoddy historical scholarship and neo-modernist ideas:

“However, in these studies concerning ancient Rites the necessary groundwork for knowledge must first be undertaken in a spirit of piety and docile and humble obedience. And if these are lacking, any research whatever into ancient liturgies of Mass will turn out to be irreverent and fruitless: for when, either through ignorance or a proud and conceited mind, the supreme authority of the Apostolic See in liturgical matters, which rightly rejects puffed-up knowledge, and, with the Apostle, ‘speaks wisdom among the perfect’ (1 Cor. 8: 1,2: 6), has been scorned, there immediately looms the danger that the error known as Modernism will be introduced also into liturgical matters.” (18)

In fact, a resurgent Modernism had gained such a foothold in Pius XII’s time that even a Protestant theologian, cheering on the progress of the Liturgical Movement from the sidelines, noted in 1954 that “It is especially in its theological method that the Liturgical Movement evidences a relationship with the errors of Modernism as condemned by Pius X in Pascendi … certain of the most fruitful trends condemned by Pius X in his blanket condemnation have served to make the Liturgical Movement the great power it is today.” (19)

Continued

- Apud Alcuin Reid, The Organic Development of the Liturgy, p. 186, as a letter to the author.

- It has been claimed that “It is impossible to overestimate the contribution of Josef Jungmann to the Second Vatican Council, above all, to the pastoral renewal of the liturgy – to the momentum for reform that had been gathering for decades, to the climate in which it unfolded, to its preparations, inner workings, implementation and reception around the world. By the time the Council was announced Jungmann was already the elder statesman of the liturgical movement whose writing, teaching and preaching had formed a generation of pastors and scholars.” Kathleen Hughes, “Jungmann’s Influence on Vatican II: Meticulous Scholarship at the Service of a Living Liturgy,” in Joanne M. Pierce and Michael Downey eds., Source and Summit: Commemorating Josef A. Jungmann, SJ, Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1999, p. 21.

- A. Bugnini, Reform of the Liturgy 1948-75, pp. 11-12.

- The first English edition was translated from German by Francis A. Brunner, CSSR, and entitled The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its origins and development, 2 vol., New York: Benzinger Brothers, 1951.

- In 1958, the English liturgist Fr Clifford Howell enthused: “There is mighty little that he holds that anyone would be inclined to dispute; for he seems to come as near to omniscience as is humanly possible. … Jungmann’s conclusions are pretty well universally accepted by the pundits. He is THE great man of the day.” (Clifford Howell, “The Parish in the Life of the Church,” Living Parish Week, Sydney, Pellegrini, 1958, p. 23)

- Louis Bouyer, Liturgical Piety, Notre Dame, Ind: University of Notre Dame Press, 1955, p. 16.

- Joseph Ratzinger, Preface to the French edition of Reform of the Roman Liturgy by Msgr. Klaus Gamber.

- See, for example, Klaus Gamber, Reform of the Roman Liturgy: Its Problems and Background, 1993, p. 5; Alcuin Reid, Organic Development of the Liturgy, 2004, pp. 151-159; and Eamon Duffy, “Fields of Faith: Theology and Religious Studies for the Twenty-first Century” in Worship, 2005, who showed convincingly that “there is in fact no warrant for supposing that an offertory procession … was ever a feature of the Roman Mass.” p. 120.

So how could it be realistically “restored,” as the reformers demanded? - When the Nazis closed down the University of Innsbruck’s Jesuit College in 1939, where Jungmann was teaching, he quickly packed his bags and decamped first to a residence in Vienna and, then, to a convent in Hainstetten run by the School Sisters of St. Polten.

Jungmann explained in the Foreword to Missarum Sollemnia, (p. vi): “Here, along with the moderate duties in a little church attached to the convent, I was granted not only the undisturbed quiet of a peaceful countryside, but – under the watchful care of the good Sisters – all the material conditions conducive to successful labor.” - During World War II, a '”funk hole” was a small private hotel or guest house in a remote part of the country where those with the necessary money could stay as permanent guests in safety and comfort.

- These included the prayers at the foot of the altar, the silent prayers of the priest including most of the Lavabo and part of the Canon and the Last Gospel. “At a minimum we would have to say today: In order that any of these prayers be retained, a justifying reason must, in each single case, be adducible.” (J. A. Jungmann, “Problems of the Missal,” Worship, vol. 28, n. 3, 1953/4, p. 155.

- Jungmann’s statement in its context follows:

"Since the Council of Trent, the understanding of the sacrifice of the Mass has often been obstructed by the apologetic tendency to overstrain its identity with the sacrifice of the Cross. … Exclusive stress upon the sacrifice of Christ, and unrestricted identification of the Mass with the sacrifice of Calvary, along with the ignoring of what we, as the Church, have to seek to do on our part, leads us away from the true liturgy of the Mass. … The sacrifice of the Mass is not the sacrifice for the redemption of the world, but the sacrifice made by the redeemed.” Josef A. Jungmann, Announcing the Word of God, trans. from the German by Ronald Walls, London: Burns and Oates, 1967, pp. 114 and 117. - “What is meant by the words Mysterium Fidei? Christian antiquity would not have referred them so much to the obscurity of what is here hidden from the senses, but accessible (in part) only to (subjective) faith. Rather it would have taken them as a reference to the grace-laden sacramentum in which the entire objective faith, the whole divine order of salvation is comprised. The chalice of the New Testament is the life-giving symbol of truth, the sanctuary of our belief. How or when or why this insertion was made, or what external event occasioned it, cannot readily be ascertained.” J. A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its origin and development, Benzinger Brothers, 1950, vol. 2, pp. 200-201.

- “I am sure it was not a mere accident that the primitive Church did not apply the term ιερευς [hiereus, “priest”] to either bishop or presbyter. … For, there is only one mediator between God and man, Jesus Christ. … The term ιερευς was therefore applicable only to Christ and to the whole communion of the faithful, the holy Church, insofar as it is joined to Christ.” J. A. Jungmann, The Early Liturgy: To the Time of Gregory the Great, University of Notre Dame Press., 1959.

- “The liturgy, the public worship of the Church, which in early times set the rhythm of Christian devotion, was, in the Middle Ages, put further and further in the background in favor of private and lay devotion. Hence subjectivism and individualism in the religious life of Catholics came strongly to the forefront. All too much leeway was given to human action in opposition to the operation of divine grace. So liturgical worship languished more and more and finally became a function of the priest, at which the people, during the liturgy and in place of it, gave themselves to private devotions. … A preliminary step to this divide was the proliferation of personal prayers, recited in a low voice by the priest. With such prayers, he already began to execute his own private ritual during the Mass.” J.A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite, vol. 1, pp. 84, 104.

- 16. For the full text of his speech (in French), see J. A. Jungmann, “La Pastorale, Clef de L’Histoire Liturgique,” (The Pastoral Approach, Key to the History of the Liturgy) La Maison-Dieu, n. 47-48, 1956.

He criticized the silent prayers of the priest as a barrier preventing the faithful from entering into the liturgy. He compared the Canon to a veil that separated the faithful from true participation in the Mass. - Session 22, Canon 9 of the Council of Trent: “If any one saith, that the rite of the Roman Church, according to which a part of the Canon and the words of Consecration are pronounced in a low tone, is to be condemned; or, that the Mass ought to be celebrated in the vulgar tongue only, … let him be anathema.”

- Pius XI, Inter multiplices (the opening words of the Introduction to the Missal of the Diocese of Braga in Portugal), Missale Bracarense, Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, 1924, p. viii: "Hisce tamen de antiquis Ritibus studiis praernittenda est debita scientiae praeparatio, quae comitern habeat pietatern ac docilem humilemque obedientiam. Quae si deficerent, profana evaderet et sterilis quaevis de antiquis Missae Liturgiis investigatio: contempta enim, sive ob ignorantiam, sive ob elaturn inflatumque animum, suprema in rebus liturgicis auctoritate Sedis Apostolicae, quae merito scientiarn repudiat inflantem et cum Apostolo sapientiarn loquitur inter perfectos (1 Cor. 8: 1,2: 6), periculum prorsus immineret ne error ille, qui modernismus audit, in res quoque liturgicas induceretur.” [Translation by C. Byrne]

- Ernest Koenker, The Liturgical Renaissance in the Roman Catholic Church, University of Chicago Press, 1954, pp. 29, 30-31

Posted October 28, 2015

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |