Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXII

Pius XII:

‘The Reforms Come from the Holy Spirit’

Pope Pius XII’s address to the participants at the Assisi Congress in 1956 contains a number of unwelcome surprises for those who thought of him as in every way a solidly traditional Pope. Just as the Congress itself had turned out to be a platform for tendentious propaganda, so the Pope’s speech reflected and perpetuated the reformers’ “narrative,” endorsing their message about “active participation” for the faithful in the liturgy.

A papal fanfare for the Liturgical Movement

In his speech, Pius XII lauded what he termed the “practical accomplishments” of the Liturgical Movement in the last 30 years. Among the “practical accomplishments” which he had so far enabled were the following:

In his speech, Pius XII lauded what he termed the “practical accomplishments” of the Liturgical Movement in the last 30 years. Among the “practical accomplishments” which he had so far enabled were the following:

And we know exactly what those goals were – the replacement of the Church’s traditional liturgy with a man-centred construct in which the “active participation” of the laity would be the predominant feature. Yet, Pius XII stated: “We sincerely desire that the Liturgical Movement progress and we wish to help it.”

A new ‘pastoral’ approach to the liturgy

These reforms represented a significant turning point in the Church’s liturgical development, the precedence of so-called “pastoral liturgy” (aimed at adapting the ceremonies to the prevailing mentality of modern man) over the objective liturgical tradition of the Church.

As Bugnini explained in his Memoirs, the Liturgical Movement, with the support of Pope Pius XII, “entered upon its true course – that of pastoral concern – and was, thus, returning to the ideal it had had in the beginning.” (3) But where does that leave the liturgy of all the intervening centuries? It was obviously to be passed over as neither “true,” nor “pastoral,” nor “ideal.”

As Bugnini explained in his Memoirs, the Liturgical Movement, with the support of Pope Pius XII, “entered upon its true course – that of pastoral concern – and was, thus, returning to the ideal it had had in the beginning.” (3) But where does that leave the liturgy of all the intervening centuries? It was obviously to be passed over as neither “true,” nor “pastoral,” nor “ideal.”

In fact, one of the speakers at the Assisi Congress, Fr. Josef Jungmann, posited that the Church’s liturgy had, since early Christian times, become “corrupted” and had lost its power to sanctify the faithful because they could neither understand nor participate in it.

The implication of this blasphemous smear on the Church’s sacred patrimony is that what we once esteemed was never really valuable in the first place. From which it follows that somewhere in its early history the Holy Spirit had departed from the Catholic liturgy, only to return in the 20th century with the new “pastoral” approach of the Liturgical Movement.

Playing to the gallery

It is undeniable that Pius XII favored this new “pastoral” approach and even thought that it bore the Divine stamp of approval. To the delight of the Assisi participants gathered in Rome, he stated:

“The Liturgical Movement is, thus, shown forth as a sign of the providential dispositions of God for the present time, of the movement of the Holy Spirit in the Church.”

If God was with it, who could be against it? A more imprudent and divisive opinion could hardly be imagined – imprudent because it seemed to imply that the traditional liturgy was grossly deficient and needed Spirit-led changes; and divisive because it signalled the Pope’s preference for the reformers, rather than the conservatives in the Church, at least on certain issues.

But, the salient point is that the Pope – or whoever wrote his speech – simply assumed that because the liturgical reforms were promoted by members of the Church, their Movement must perforce enjoy Divine approval. His statement that “the chief driving force, both in doctrine and in practical application, has come from the hierarchy” is deeply troubling for two reasons.

But, the salient point is that the Pope – or whoever wrote his speech – simply assumed that because the liturgical reforms were promoted by members of the Church, their Movement must perforce enjoy Divine approval. His statement that “the chief driving force, both in doctrine and in practical application, has come from the hierarchy” is deeply troubling for two reasons.

First, it is an admission devastating in its implications. It reveals that it was the Church’s leaders, including the Pope himself, who were the driving force behind the international effort to reform the liturgy. In other words, it was the Pastors, more so than the liturgists, who were responsible for driving the sheep towards a liturgical cliff over which they would fall with astonishing suddenness within a few years.

However, only a tiny minority of Bishops at that time favored the reforms; and at the beginning of his pontificate most did not even have the slightest suspicion that such reforms were being planned. It is incomprehensible, therefore, that he should seek to alter the spirituality of Catholics who valued the Church’s traditions to suit those who did not.

Second, the Pope talked as if the reforms were unimpeachably orthodox “both in doctrine and in practical application” as if the lex credendi were in perfect accord with the lex orandi. Here we are not addressing the orthodoxy of Pius XII’s magisterial teaching on matters of Catholic doctrine. But to the degree that his reforms promoted “active participation” of the laity in the sacred functions, they introduced a tension between the Faith and pastoral practice. The laity was now seen to be “on the move” against a “despotic” clergy, who had allegedly robbed them of their rightful roles in the liturgy, to take back what belonged to them by virtue of their Baptism. The clergy-laity class struggle had been the raison d’être of the Liturgical Movement since its inception by Dom Lambert Beauduin.

Even though Pius XII taught the true doctrine of the Catholic priesthood, he nevertheless gave official impetus to the rolling revolution of lay “active participation,” which challenged the exclusive role of the priest. By promoting this competitive spirit, he initiated the process that turned the liturgy into an ideological battleground which continues to our day, to the detriment of the ministerial priesthood and the confusion of the faithful.

Pius XII misled by false propaganda

Much of Pius XII’s Assisi speech echoed the desiderata which the reformers had been putting forward in their various congresses and publications. The fact that the forces of Progressivism should play a pivotal role in the Pope’s speech is highly significant. It shows that he was swayed by their rhetoric in making policy decisions for the rest of the Church. He took their word for it that “the faithful received these directives with gratitude and showed themselves ready to respond to them.”

But, that was pure fabrication put about by Bugnini, who had massaged the results of the liturgical Commission’s surveys to give the misleading impression of general acceptance. For all his efforts, Bugnini had not produced evidence that was in reality objectively convincing or statistically significant.

Also, the reformers had been spreading a false sense of despondency about how useless the traditional rites were and claiming that the faithful welcomed with relief all the new, exciting initiatives that were on offer.

There was no general euphoria among the Catholic population, clerical or lay, in response to the reforms. In fact, the reformers themselves complained for years about the lack of enthusiasm for “active participation” and the extreme difficulty in getting the faithful to say or sing the responses. Besides, it is dishonest to claim that the laity accepted the reforms with joy on the basis of their presence at ceremonies, which they attended out of duty and obedience.

Continued

A papal fanfare for the Liturgical Movement

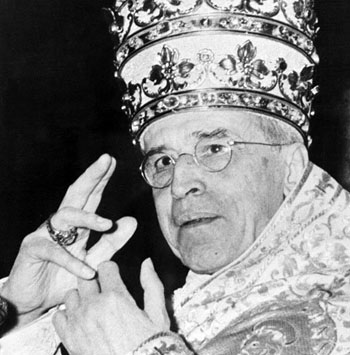

Pius XII in 1956, Conservative in appearance but already deep in the Liturgical Reform

- The vernacular could be used in the administration of the Sacraments;

- The faithful could recite aloud the server’s responses during Mass and sing along with the choir;

- Women were officially permitted, albeit under certain conditions, to sing in the choir; (1)

- The 1955 Holy Week liturgy, particularly the Easter Vigil, was gutted and reconstructed to cater for “active participation” of the laity;

- In some ceremonies the celebrant was required to face the people and there was an optional dialogue in the vernacular;

- The Breviary was drastically shortened (“simplified”) as the precursor to a more thorough reform incorporating the wishes of the progressivists. In the Opening Speech of the Assisi Congress in 1956, Cardinal Cicognani said that the “simplification of the rubrics was the forerunner of the eventual reform of the Breviary.” (2)

And we know exactly what those goals were – the replacement of the Church’s traditional liturgy with a man-centred construct in which the “active participation” of the laity would be the predominant feature. Yet, Pius XII stated: “We sincerely desire that the Liturgical Movement progress and we wish to help it.”

A new ‘pastoral’ approach to the liturgy

These reforms represented a significant turning point in the Church’s liturgical development, the precedence of so-called “pastoral liturgy” (aimed at adapting the ceremonies to the prevailing mentality of modern man) over the objective liturgical tradition of the Church.

Progressivist Fr. Jungmann accused the traditional rite of losing its power to sanctify

In fact, one of the speakers at the Assisi Congress, Fr. Josef Jungmann, posited that the Church’s liturgy had, since early Christian times, become “corrupted” and had lost its power to sanctify the faithful because they could neither understand nor participate in it.

The implication of this blasphemous smear on the Church’s sacred patrimony is that what we once esteemed was never really valuable in the first place. From which it follows that somewhere in its early history the Holy Spirit had departed from the Catholic liturgy, only to return in the 20th century with the new “pastoral” approach of the Liturgical Movement.

Playing to the gallery

It is undeniable that Pius XII favored this new “pastoral” approach and even thought that it bore the Divine stamp of approval. To the delight of the Assisi participants gathered in Rome, he stated:

“The Liturgical Movement is, thus, shown forth as a sign of the providential dispositions of God for the present time, of the movement of the Holy Spirit in the Church.”

If God was with it, who could be against it? A more imprudent and divisive opinion could hardly be imagined – imprudent because it seemed to imply that the traditional liturgy was grossly deficient and needed Spirit-led changes; and divisive because it signalled the Pope’s preference for the reformers, rather than the conservatives in the Church, at least on certain issues.

The Assisi Papers were approved by Pius XII - a huge step forward for Liturgical Reform

First, it is an admission devastating in its implications. It reveals that it was the Church’s leaders, including the Pope himself, who were the driving force behind the international effort to reform the liturgy. In other words, it was the Pastors, more so than the liturgists, who were responsible for driving the sheep towards a liturgical cliff over which they would fall with astonishing suddenness within a few years.

However, only a tiny minority of Bishops at that time favored the reforms; and at the beginning of his pontificate most did not even have the slightest suspicion that such reforms were being planned. It is incomprehensible, therefore, that he should seek to alter the spirituality of Catholics who valued the Church’s traditions to suit those who did not.

Second, the Pope talked as if the reforms were unimpeachably orthodox “both in doctrine and in practical application” as if the lex credendi were in perfect accord with the lex orandi. Here we are not addressing the orthodoxy of Pius XII’s magisterial teaching on matters of Catholic doctrine. But to the degree that his reforms promoted “active participation” of the laity in the sacred functions, they introduced a tension between the Faith and pastoral practice. The laity was now seen to be “on the move” against a “despotic” clergy, who had allegedly robbed them of their rightful roles in the liturgy, to take back what belonged to them by virtue of their Baptism. The clergy-laity class struggle had been the raison d’être of the Liturgical Movement since its inception by Dom Lambert Beauduin.

Even though Pius XII taught the true doctrine of the Catholic priesthood, he nevertheless gave official impetus to the rolling revolution of lay “active participation,” which challenged the exclusive role of the priest. By promoting this competitive spirit, he initiated the process that turned the liturgy into an ideological battleground which continues to our day, to the detriment of the ministerial priesthood and the confusion of the faithful.

Pius XII misled by false propaganda

Much of Pius XII’s Assisi speech echoed the desiderata which the reformers had been putting forward in their various congresses and publications. The fact that the forces of Progressivism should play a pivotal role in the Pope’s speech is highly significant. It shows that he was swayed by their rhetoric in making policy decisions for the rest of the Church. He took their word for it that “the faithful received these directives with gratitude and showed themselves ready to respond to them.”

But, that was pure fabrication put about by Bugnini, who had massaged the results of the liturgical Commission’s surveys to give the misleading impression of general acceptance. For all his efforts, Bugnini had not produced evidence that was in reality objectively convincing or statistically significant.

Also, the reformers had been spreading a false sense of despondency about how useless the traditional rites were and claiming that the faithful welcomed with relief all the new, exciting initiatives that were on offer.

There was no general euphoria among the Catholic population, clerical or lay, in response to the reforms. In fact, the reformers themselves complained for years about the lack of enthusiasm for “active participation” and the extreme difficulty in getting the faithful to say or sing the responses. Besides, it is dishonest to claim that the laity accepted the reforms with joy on the basis of their presence at ceremonies, which they attended out of duty and obedience.

Continued

- See the Encyclical Musicae Sacrae (Of Sacred Music), 25 December 1955, § 74. The document allows female choristers on the lame excuse “where there are not enough boys” to sing in church. But how few are “not enough?” Men (of whom there was never a shortage in those days) could always have been recruited to make up the numbers. As with the altar server debacle of the 1990s, the best way to ensure a dearth of boys in liturgical roles is to have girls perform alongside them.

- La Maison-Dieu, No. 47-8, 1956, pp. 44-5

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy, p. 6

Posted August 5, 2015

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |