Traditionalist Issues

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dialogue Mass - XXI

Liturgical Anarchy Increases under Pius XII

From 1955, it was becoming clear that Pope Pius XII was yielding ground to a “managerial” caucus of liturgical experts who saw themselves as indispensable organizers of a new liturgy for the Church. From random beginnings in various countries under the leadership of notable personalities such as Dom Lambert Beauduin, Ildefons Herwegen, Pius Parsch, Romano Guardini, Virgil Michel and Annibale Bugnini, they coalesced into organized pressure groups with some episcopal support.

Pius XII was evidently aware early in his pontificate that a liturgical revolution was being planned, for he reprimanded some deviations from tradition in Mediator Dei (1947).

Pius XII was evidently aware early in his pontificate that a liturgical revolution was being planned, for he reprimanded some deviations from tradition in Mediator Dei (1947).

We must not lose sight of the fact that these deviations were taking place precisely because of lack of ecclesiastical control. Pius XII’s verbal reprimands were not matched by corrective actions to prevent recurrence. He did not take steps to remove from office Bishops who were involved in liturgical revolution, replace them with more worthy candidates and require them to discipline radical priests.

It is simply inconceivable that he could not have mustered adequate support from among the world’s conservative Bishops – it was after all the age of Ultramontanism – to neutralize the effects of the Liturgical Movement. Despite his public breast-beating, the problem was that liturgical anarchy was inexorably increasing under his watch. And as he failed to give a firm and consistent signal of a united effort to defeat such dissident tactics, the progressivists became emboldened and gradually gained the upper hand. Anti-traditional challenges to authority went unchecked

Their radical agenda was expressed in internationally known journals (1) and also at international congresses held in the early 1950s: at Maria Laach (Germany), Mont Sainte-Odile (France), Lugano (Switzerland), Mont-César (Louvain, Belgium) and Assisi (Italy).

It is not an exaggeration to say that these congresses were characterized by a climate of seething mutiny against the Church’s sacred liturgical traditions. It was as if a simmering cauldron was slowly coming to the boil, the fire beneath it fueled by animosity to centuries of liturgical tradition.

At Maria Laach (1951)

The following points, unanimously accepted by the delegates, were among 12 resolutions to be forwarded to the Holy See:

This meeting largely continued the requests made at Maria Laach with some additions:

The following resolutions were approved by the entire assembly which included Cardinal Ottaviani and Cardinal Frings of Cologne, 15 Archbishops and Bishops and hundreds of priests:

He did not seem to mind that the Congress had been organized by the Liturgical Institute of Trier and the Centre de Pastorale Liturgique to further their revolutionary agendas; or that among the participants were those who sought to destroy Tradition e.g. Bugnini, Bishop Albert Stohr of Mainz and Bishop Simon Landersdorfer of Passau (the latter two jointly head of the Liturgical Commission appointed by the German Episcopal Conference to represent all the dissident reformers of the German-speaking lands including Guardini and Pius Parsch.)

Second, Cardinal Ottaviani (famous for his Intervention), celebrated Mass facing the people – a particularly prophetic gesture foreshadowing his defeat by the progressivists at Vatican II.

The Mont-César Conference (1954)

The meeting featured two themes:

Assisi Congress (1956)

As the whole ground plan for the future Novus Ordo was already drawn up in the previous congresses, the Assisi participants simply put the finishing touches to their radical agenda. The Congress descended into a self-congratulatory “smugfest” with participants preening themselves on the righteousness of their cause and on their success in wresting so many concessions from the Pope.

In their papers read out at the Congress, they lavished the highest praise on the Holy Father for his “admirable initiatives in the field of pastoral liturgy.” (8) Who would have thought that Pius XII would become the toast of the liberals?

In their papers read out at the Congress, they lavished the highest praise on the Holy Father for his “admirable initiatives in the field of pastoral liturgy.” (8) Who would have thought that Pius XII would become the toast of the liberals?

From Assisi, the Congress moved to Rome where it concluded with the Pope’s address to the participants. In it, Pius XII stated that the Liturgical Movement was “a sign of the providential dispositions of God for the present time, of the movement of the Holy Ghost in the Church.”

Thus, he helped to build a positive image of the Liturgical Movement for public consumption, with the result that what had once been a hole-in-the-corner activity and an isolated phenomenon lacking any great prestige, was put firmly on the map and made ready to become a mainstream activity.

Bugnini’s cock-a-doo of victory

Bugnini crowed with delight: “Who would have predicted at that time that three years later the greatest ecclesial event of the century, Vatican Council II, would be announced, in which the desires expressed at Assisi would be fulfilled, and this by means of the very men who were present at Assisi?” (9)

He was right in one respect – many of the Assisi delegates would later exert enormous influence in determining the course of Vatican II and creating the content of some of its documents. (10) However, his powers of prediction seemed to have deserted him when he declared that the event “was, in God’s plan, a dawn announcing a resplendent day that would have no decline.” (11)

Summoning the Apocalypse

The summons of the Assisi participants to Rome to be greeted by the Pope can be seen as a papal endorsement of their agenda. Fr. Löw of the Sacred Congregation of Rites stated that the organizers of the Assisi Congress “were the four centers of liturgical effort in Germany, France, Italy and Switzerland.” (12)

He might as well have said the Four Horses of the Apocalypse because of the chaos, anarchy and destruction that reigned as a result of the Liturgical Movement and Vatican II.

Continued

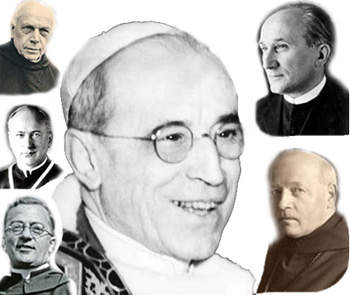

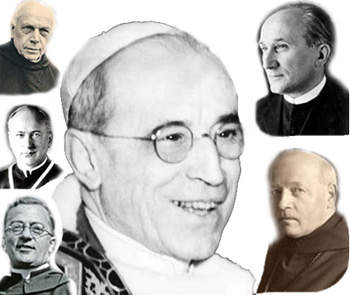

Pius XII surrounded by liturgical reformers: Left, top to bottom, Beauduin, Parsch & Michel; right, Guardini & Herwegen

We must not lose sight of the fact that these deviations were taking place precisely because of lack of ecclesiastical control. Pius XII’s verbal reprimands were not matched by corrective actions to prevent recurrence. He did not take steps to remove from office Bishops who were involved in liturgical revolution, replace them with more worthy candidates and require them to discipline radical priests.

It is simply inconceivable that he could not have mustered adequate support from among the world’s conservative Bishops – it was after all the age of Ultramontanism – to neutralize the effects of the Liturgical Movement. Despite his public breast-beating, the problem was that liturgical anarchy was inexorably increasing under his watch. And as he failed to give a firm and consistent signal of a united effort to defeat such dissident tactics, the progressivists became emboldened and gradually gained the upper hand. Anti-traditional challenges to authority went unchecked

Their radical agenda was expressed in internationally known journals (1) and also at international congresses held in the early 1950s: at Maria Laach (Germany), Mont Sainte-Odile (France), Lugano (Switzerland), Mont-César (Louvain, Belgium) and Assisi (Italy).

It is not an exaggeration to say that these congresses were characterized by a climate of seething mutiny against the Church’s sacred liturgical traditions. It was as if a simmering cauldron was slowly coming to the boil, the fire beneath it fueled by animosity to centuries of liturgical tradition.

At Maria Laach (1951)

The following points, unanimously accepted by the delegates, were among 12 resolutions to be forwarded to the Holy See:

An historic liturgical meeting at the Benedictine Maria Laach Abbey in the Rhineland, Germany

- Reform of the priest’s silent prayers (including the Offertory) during Mass;

- Significant changes to the Roman Canon; (2)

- Suppression of the prayers at the foot of the altar (citing the Easter Vigil reform as a precedent);

- All of the Mass up to the Preface to be said away from the altar denuded of sacred vessels;

- A longer cycle of scriptural readings, all in the vernacular only;

- Introduction of bidding prayers with vernacular responses by the faithful;

- Less frequent recitation of the Credo;

- Elimination of the Confiteor before Communion;

- Suppression of all prayers after the Blessing i.e. the Last Gospel and the Leonine prayers. (3)

This meeting largely continued the requests made at Maria Laach with some additions:

- Elimination of some of the celebrant’s genuflexions, Signs of the Cross and kissing of the paten;

- Simplification of the formula of Communion of the faithful to “Corpus Christi”;

- Increased opportunities for the faithful to join in the singing of the Mass, especially by newly composed melodies in the vernacular at Communion time.(4)

The following resolutions were approved by the entire assembly which included Cardinal Ottaviani and Cardinal Frings of Cologne, 15 Archbishops and Bishops and hundreds of priests:

- Increased “active participation” of the laity, supported by a message from Mgr Montini in Rome;

- The laity to “pray and sing in their own tongue even during a Missa Cantata;” (5)

- All Scripture readings to be in the vernacular;

- Revision of all ceremonies of Holy Week in line with the recently revised Easter Vigil.

He did not seem to mind that the Congress had been organized by the Liturgical Institute of Trier and the Centre de Pastorale Liturgique to further their revolutionary agendas; or that among the participants were those who sought to destroy Tradition e.g. Bugnini, Bishop Albert Stohr of Mainz and Bishop Simon Landersdorfer of Passau (the latter two jointly head of the Liturgical Commission appointed by the German Episcopal Conference to represent all the dissident reformers of the German-speaking lands including Guardini and Pius Parsch.)

Second, Cardinal Ottaviani (famous for his Intervention), celebrated Mass facing the people – a particularly prophetic gesture foreshadowing his defeat by the progressivists at Vatican II.

The Mont-César Conference (1954)

The meeting featured two themes:

- A more extended cycle of scriptural readings at Mass;

- A new rite of concelebration.

Assisi Congress (1956)

As the whole ground plan for the future Novus Ordo was already drawn up in the previous congresses, the Assisi participants simply put the finishing touches to their radical agenda. The Congress descended into a self-congratulatory “smugfest” with participants preening themselves on the righteousness of their cause and on their success in wresting so many concessions from the Pope.

At the Congress of Assisi in 1956 a group of Americans with Fr. Godfrey Diekmann at the head of the table

From Assisi, the Congress moved to Rome where it concluded with the Pope’s address to the participants. In it, Pius XII stated that the Liturgical Movement was “a sign of the providential dispositions of God for the present time, of the movement of the Holy Ghost in the Church.”

Thus, he helped to build a positive image of the Liturgical Movement for public consumption, with the result that what had once been a hole-in-the-corner activity and an isolated phenomenon lacking any great prestige, was put firmly on the map and made ready to become a mainstream activity.

Bugnini’s cock-a-doo of victory

Bugnini crowed with delight: “Who would have predicted at that time that three years later the greatest ecclesial event of the century, Vatican Council II, would be announced, in which the desires expressed at Assisi would be fulfilled, and this by means of the very men who were present at Assisi?” (9)

He was right in one respect – many of the Assisi delegates would later exert enormous influence in determining the course of Vatican II and creating the content of some of its documents. (10) However, his powers of prediction seemed to have deserted him when he declared that the event “was, in God’s plan, a dawn announcing a resplendent day that would have no decline.” (11)

Summoning the Apocalypse

The summons of the Assisi participants to Rome to be greeted by the Pope can be seen as a papal endorsement of their agenda. Fr. Löw of the Sacred Congregation of Rites stated that the organizers of the Assisi Congress “were the four centers of liturgical effort in Germany, France, Italy and Switzerland.” (12)

He might as well have said the Four Horses of the Apocalypse because of the chaos, anarchy and destruction that reigned as a result of the Liturgical Movement and Vatican II.

Continued

- The most well known were Virgil Michel’s Orate Fratres (renamed in 1951 as Worship) published at St. John’s Benedictine Abbey, Minnesota; Bugnini’s Ephemerides Liturgicae published in Rome; and La Maison-Dieu published by Editions du Cerf for the Centre de Pastorale Liturgique in Paris.

- This altogether staggering suggestion to overhaul the Roman Canon, hitherto considered for 15 centuries so sacred as to be untouchable, was not recorded in the original published conclusions of the Maria Laach Congress. But it was recorded by one of the participants, Dom Bernard Botte, OSB, in his memoirs: Le Mouvement Liturgique: Témoinage et Souvenirs, Paris: Desclée et Compagnie, 1973, pp. 80-81. Here he stated that a resolution to make significant changes to the Canon was part of a talk given by Fr. Josef Jungmann, SJ.

- ‘Conclusions of the First International Congress of Liturgical Studies held at Maria Laach in 1951: Problems of the Roman Missal’, La Maison-Dieu, n. 37, 1954, pp. 129-131.

- ‘Conclusions of the Second International Congress of Liturgical Studies held at Sainte-Odile in 1952: Problems of the Roman Missal’, La Maison-Dieu, n. 37, 1954, pp. 132-133.

- ‘Conclusions of the Third Congress, Lugano, 1953’, Worship, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, vol. 28, February 1954, p. 162. Vernacular singing at a sung Mass had been expressly forbidden by both Leo XIII and Pius X.

- The message read: “Our good wishes go with the proceedings of this scholarly assembly and We warmly extend Our Apostolic Blessing to all and each one of the participants.” (Nous accompagnons de Nos voeux les travaux de cette savante assemblée et Nous accordons de tout coeur à tous et à chacun des participants la Bénédiction Apostolique.) La Maison-Dieu, n.. 37, 1954, p. 3.

- Fr. Godfrey Diekmann OSB, ‘Louvain and Versailles’, Worship, vol. 28, 1954, p. 54.

- Gaetano Cicognani, ‘Opening Address’ of the Congress

- A. Bugnini, The Reform of the Liturgy 1948-1975, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1990, p. 11.

- The Cardinals participating were Gaetano Cicognani, Prefect of the Congregation of Rites and President of the Preparatory Commission on the Liturgy, Augustin Bea, SJ, confessor of Pius XII and President of the Commission for Christian Unity at Vatican II, Pierre-Marie Gerlier of Lyon, a noted ecumenist and liberation theologian, Gabriel Garrone of Toulouse, who helped formulate Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes, and Giacomo Lercaro of Bologna, who contributed an extremely radical paper on the reform of the Breviary and later became one of the four Moderators of Vatican II.

Other participants who played an active role in Vatican II were Fr. (later Cardinal) Antonelli; Bishop Wilhelm van Bekkum of Ruteng, Indonesia (on adapting the liturgy to local customs and languages); Bishop Otto Spuelberg of Meissen, who championed Teilhard de Chardin at Vatican II as “a great scientist”; and Fr. Joseph Jungmann, SJ, who promoted antiquarianism and the supremacy of pastoral initiatives over objective tradition. Jungmann was later appointed relator of the sub-commission that drafted the schema on the Mass. As a peritus (expert) at Vatican II, he contributed in large part to the writing of the document on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium.

Two militantly reformist prelates, Bishops Edwin Vincent O’Hara of Kansas City and Albert Stohr of Mainz, contributed with papers to the Assisi Congress but died before Vatican II. Nevertheless, there is every reason to believe that their destructive legacy was not without influence on the Council. - 11. A. Bugnini, op. cit., p. 11

- 12. ‘Assisi 1956 and Holy Week 1957’, Worship, vol. 31, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1957, p. 236

Posted June 19, 2015

______________________

______________________

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

Volume VII |

Volume VIII |

Volume IX |

Volume X |

Volume XI |

Special Edition |