|

The Saint of the Day

St. Anno of Cologne – December 4

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

Anno (1010-1075) was one of the great saints of the early times of the Holy Roman German Empire. His eminent deeds were recorded not only in History, but also literature, for his life was written in a poem of 876 stanzas called the Annoniada – a classical work in medieval German literature.

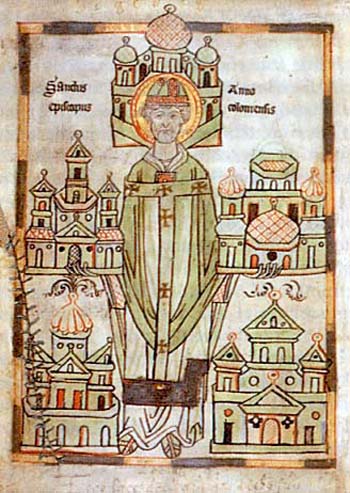

St. Anno depicted with the monasteries he founded

|

Named Archbishop of Cologne in 1055, he also held the titles of professor in the School of Bamberg, Chancellor of the Holy Empire, and founder of monasteries. To him is due in part Germany’s introduction to the Cluny reform of monks.

He had a majestic bearing, was a great orator and was skillful in conversation. His classes and talks held the attention of all who heard him. He was admired for his learning and orthodoxy of thought. His renowned amenity combined with a legendary energy imposed respect and veneration.

In 1062, a difficult period in the Empire, he saved the Gregorian Reform from a crisis that could have been fatal to it. Stephen IX – the first Pope to be elected without consultation of the Emperor – sent the Monk Hildebrand (the future St. Gregory VII) to convince Empress Agnes, who was governing as regent on behalf of her underage son, the future Henry IV, to recognize his election. The Empress readily acquiesced.

But Stephen IX died before the return of Hildebrand. The next Pope was Nicholas II, who at first was also recognized by the Empress. However, problems sparked when Nicholas II decreed that the election of the Popes should be made by the College of the Cardinals. The nobility and clergy of Rome – who thus far had exercised the role of electing the Pope – revolted and the adversaries of the Gregorian Reform convinced the Empress not to accept the papal decree.

Nicholas II died soon afterwards and the Sacred College elected Alexander II. However, the Bishops of Lombardy along with some German Bishops elected an anti-pope, with the approval of the Empress, who took the name of Honorius II. The latter marched to Rome to threaten Nicholas’ position. It was a difficult situation since against Nicholas was the Holy German Empire. In this crucial moment St. Anno intervened.

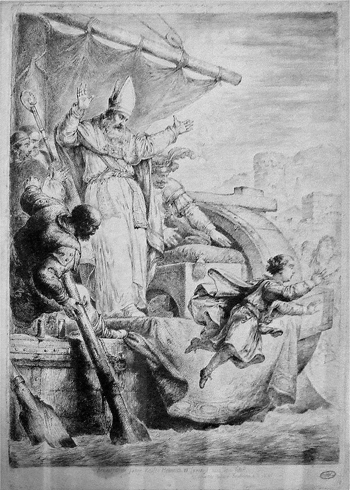

The boy Henry IV attempts to flee the boat but fails |

As Chancellor, Anno knew the customs of the Empress. She would generally stop to rest on a river island on the Rhine called Werth when she had to travel. So, the Saint built a marvelous boat and waited for her next journey. When the time came for her to travel, he went to the island and invited her son – the future Emperor – to ride with him in the boat.

Once the boy, age 11, was in the boat, Anno kidnapped him in what is called the Coup of Kaiserwerth and took him to Cologne, his Archdiocese. There, he convened an assembly of German nobles to discuss the validity of that regency. The great nobles of Germany gathered and, after due study of the case, determined that the Empress should no longer exercise the regency and that it should be given to St. Anno, Archbishop of Cologne.

Next, on October 27, 1062, St. Anno presided over a synod in Augsburg at which the decree of Pope Nicholas II was accepted and the election of Pope Alexander II recognized, Duke Godfrey of Lorena was assigned to bring the Pope to Rome and guarantee that he would take possession of the city. The Gregorian Reform was saved.

This is one action that show the decisive role played by St. Anno in the affairs of the time.

Some years later, Empress Agnes, who had retired to a convent, repented of her earlier support for the anti-pope Honorius II. She went to Rome as a penitent – dressed in sackcloth and holding a rope around her neck – to asked forgiveness of the Pope. The Pope sent St. Peter Damian to receive her and absolve her and the Saint afterwards became her confessor.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

From the description of St. Anno, you see that he was one of these classic men, physically well constituted and with these two strong characteristics: on the one hand, an amenable man who knew how to treat others well and a skillful orator, brilliant in conversation and, on the other hand, a very forceful man.

St Anno produced respect & veneration

|

Liberalism always dislikes this picture: a truly forceful person who is amiable with others. The reciprocal should also be true: the person with a pleasant approach must be energetic and compelling when necessary.

What is a pleasant approach with others? It is not to tell jokes. It is to deal with themes that divert and please, but at the same time elevate and dignify the others. This was the approach of St. Anno.

This selection mentions the Gregorian Reform several times. Before the pontificate of St. Gregory VII, the Church was passing through tremendous crises and a momentous moral decline. Those crises were all corrected by the Gregorian Reform.

The name came from the leader of the Reform, who was St. Gregory VII. But, even before he became Pope, the Monk Hildebrand – as he was then known – influenced several Popes who had been his disciples. After he died, his influence continued since other disciples of his were also elected Popes and continued his work. This ensemble of Popes marked by him as well as his own pontificate made a movement for the restoration of the Church, which is one of the most significant movements the Church knows. This is what is called the Gregorian Reform.

The background to the intervention of St. Anno recounted here involves a very important political question. As you know, the election of the Holy Father has always been one of the most decisive appointments in world politics. It continues to be so in our days. For example, the election of Msgr. Montini as Pope Paul VI carried the weight to increase the influence of the USSR all over the world.

You can imagine in the Middle Ages, when the world was much more Catholic than today, how sensitive the role of the Pope was. So, the election of the Pope was of enormous consequence. Another question was also critical: Who should elect the Pope?

Gregory VII, inspirer of the Gregorian Reform

|

From this selection, you see that two different camps became defined. One considered that the nobles and clergy of Rome were capable of electing the Pope; the other believed that the Pope should be elected by the Sacred College. Strictly speaking, this is not a question of divine institution so the Church could decide to entrust this power to the nobles and clergy of Rome or even just to the people of Rome.

But, for the sake of convenience, that is, to ensure a clean election of a Pope worthy of the position, it was much more preferable in that time that the choice be made by the Sacred College since it represented the better aspects of the Church, a good aristocracy inside the Church. These Prelates were the most eminent persons of their generation, more prepared and stable. The word cardinal comes from the Latin – cardinalis – which means “serving as a hinge.” The root of this word is the noun cardo, meaning hinge.

Those men are for the Church what hinges are for a door: they hold the door to the framework and allow it to move, to have flexibility, they are essential for the Pope to act.

It was normal, therefore, that this summit of collaborators of the various prior Popes, who were already participating in the government of the Church, knew better than anyone else the needs of the Church throughout the world and also knew well those who could best exercise the papacy. To have this body electing the Pope was certainly more appropriate than allowing the choice to be made by the clergy of Rome, whose members were much less eminent than the cardinals.

Likewise, the nobles of Rome were not as suitable to elect the Pope. They were small feudal lords on the outskirts of Rome who would choose the Pope according to their own advantages or those of their families. So, it was natural that the Gregorian Reform wanted to transfer that election from the nobles and clergy of Rome to the College of Cardinals.

When Monk Hildebrand suggested to one of the Popes that he transfer this election to the Cardinals, it obviously raised the indignation of the nobility and clergy of Rome, because they would lose political influence. In response, they ran to the Empress to ask her support. Normally speaking, the Emperor and the Empress had an interest in keeping the election as it was, because it was much easier for them to influence the nobles and clergy of Rome than the College of the Cardinals.

This explains the clash of the two currents and the crisis that the Gregorian Reform was facing.

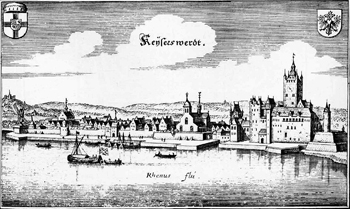

The Isle of Werth, renamed Kaiserwerth, below, ruins of the palace where Empress Agnes used to stay |

To resolve the situation, St. Anno arranged a way to kidnap the 11-year-old Emperor and bring him to Cologne, where an assembly of nobles would decide whether the regency should remain with his mother, the Empress, or pass to him to supervise the underage Emperor. This was the political situation.

Regarding the liceity of the action of St. Anno, I do not venture an opinion. My reasoning is quite simple: If this is what St. Anno did, then it should be licit. Nonetheless, I did not realize that it was.

So, St. Anno was elected Regent by the ensemble of the great German nobles and he decided in favor of the election of the Pope by the College of Cardinals. With this, the Gregorian Reform passed through the crisis and went ahead.

The report of the penance of the Empress is also impressive. She had done wrong when she supported the party of the anti-pope Honorius II. After that, she retired to a convent and, at a certain moment she decided she needed to ask public forgiveness from St. Gregory VII.

Instead of going to Rome and requesting a private audience with the Pope or his friend, St. Peter Damian, she made a much more radical decision: She went as a public penitent to Rome. She wanted to make a public act because the people were aware of her sin. So, she went dressed in sackcloth with a rope around her neck – symbolizing that her sentence could be the severe one of hanging. Let us not forget that she was the highest lady of all Christendom.

After she was forgiven, she became a friend of St. Peter Damian who had acted against the anti-pope Honorius II. She delivered her soul to be directed by the one she had offended. You see the beauty of the scene. St. Peter Damian, seeing the Empress shabbily dressed and kneeling before him, might have thought about the times she had created problems for the Popes and now had become like a lamb tamed by grace. He would have been charmed by the work of the grace, which is the only thing that makes possible such transformations in human souls. This is the Middle Ages…

Today, the sense of gravity of sin has disappeared. People only remember their sins in order to be forgiven, and only remember forgiveness in order to sin more tranquilly. This is the mentality of the modern man, the mentality of the Revolution.

How many people today should be doing public penances! But, no, it is enough for them to approach a confessional, whisper a mea culpa, and hear that they are forgiven, with no one ever imagining they should make public penance as reparation. This attitude results from weakness and liberalism, even in the confessors. All these things create the twilight in which we live, the waning of Christian Civilization.

Let us look at the Middle Ages and figures like St. Anno to understand better the true physiognomy of the Church.

|

|

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|