|

The Saint of the Day

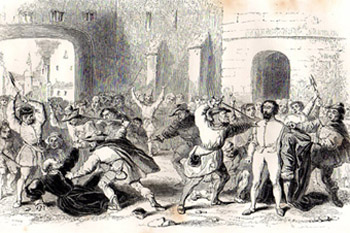

French Martyrs - September Massacres

September 2

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Selection:

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy of April 13, 1791, was condemned as heretical, schismatic and sacrilegious: Heretical because it implicitly denied the authority of the Supreme Pontiff; schismatic because it separated the Church of France from Rome and reduced it to a National Church; sacrilegious for the reforms it intended to impose on the Church and the Clergy.

On September 2 revolutionary mobs massacred the faithful priests

|

There is a close relationship between the refusal to swear to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the September Massacres. The honor of the faithful priests could not be corrupted by the threat of being killed. The revolutionary factions, irritated, had decided to do away with the leaders of that resistance. Between August 11 to 30 of 1792, more than 250 priests were imprisoned in various prisons of Paris – some in Carmel, others in La Force, others in Saint Firmin.

Among the prisoners were three Prelates, the superior general of the Marists, the superior of the Eudists, the general secretary of the Christian Brothers, parish priests, Benedictines, Jesuits, Franciscans, Capuchins, Sulpicians and others. God wanted all the classes of secular and regular clergy to be represented on the coming day of supreme testimony.

These men were not conspirators, they had not betrayed their country. They had simply refused to swear to a Civil Constitution of the Clergy that called for them to accept the principles of the French Revolution. For a priest to sign that Constitution was tantamount to delivering the Church to the State. Their consciences could not permit them to do this. And thus they preferred to die, concurring with the courageous words of the Bishop of Sens: “If God permits us to perish for so beautiful a cause, we should rejoice. This means that we were judged worthy to suffer for Him!”

On the afternoon of September 2, the revolutionary mobs broke into those prisons shouting to the priests: “Take the oath!” When they refused, they massacred them with blows from guns and swords. Most of the bodies were transported to the cemetery of Vaugirard, where large pits had been prepared the day before. Some of the bodies were thrown in a well of the Carmelite Monastery. Later, searches were made, and a large number of skulls and bones were found showing the marks of the blows they had received, as can be verified in the crypt of the Church of Carmel in Paris where they are kept.

The September martyrs were not forgotten after the Terror. In 1798 Pius VI gave them the name “choir of martyrs.” On October 17, 1926, Pope Pius XI beatified 191 of them.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

The commentary that this episode merits is one identical to the most beautiful aspects that could be said about the Dialogue of the Carmelites. (1) We have here more than two hundred priests who, placed between martyrdom and apostasy, preferred the former.

They were faithful to their priestly conscience and refused to sign an act that, on the one hand, signified their apostasy, since the French Church born from the Civil Constitution of the Clergy denied the authority of the Pope, conferring to him just an honorific role. On the other hand, it was the proclamation of the republic inside the Church.

Priests signing the Civil Constitution of the Clergy

|

According to that revolutionary Constitution, the Pope did not have any doctrinal power. Free examination thus entered that French Church. It was a kind of Protestantism.

It was also the republicanization of the Church, because all its important offices were chosen by the vote of the people, without any decision of the Pope. The bishops, after being elected, simply sent notice to the Pope and rendered him a homage that was nothing more than a greeting. That is to say, the past unity of the Church was completely fractured in that New Church.

That representative group of Catholic clergy, when intimated to sign that Constitution, did not accept it. They preferred to die.

This is something very beautiful, but in the case of those priests, there is something special.

Among those priests were a few zealous priests, and many lukewarm ones. The good priests were those few who still had the fidelity, let us say, of a St. Louis Grignion de Montfort. Remember that St. Grignion de Montfort was treated very badly by the Episcopate and the clergy. He was the object of such scorn, that once, after leaving a monastery where he had asked to sleep, he commented: “I did not imagine it possible for a priest to be treated in this way.” You see how far things had gone! This was the hatred that there was inside the clergy against the Marian spirit he represented. And, truly, all the best priests were in marginal positions in the French Clergy.

In general, that same bad spirit remained in the clergy of France until the eve of the French Revolution. The majority of the clergy was either bad or lukewarm.

The Carmelites of Compiègne were prepared to face the guillotine

|

The few faithful priests can be measured by the direction they gave to their subordinates, including some admirable nuns like the Carmelites of Compiègne, who also became martyrs in the French Revolution.

I once read in a comment of a visitor to the Carmelite Convent of Compiègne at the time right before their martyrdom. He said that the perfection of those nuns was such that their superiors could hardly find a reprimand to make in order to satisfy their humble desire to be censured. He could not find any. And thus he could do nothing except to praise them. So, when he saw them, they were all disposed for martyrdom, and they walked toward it with a great heroism.

There is a grand beauty in seeing these spouses of Christ so well prepared for the coming of the Bridegroom.

Those nuns obviously were oriented by some very good priests. So, there were a few good priests but the majority were lukewarm.

When the storm of the French Revolution burst, those priests - relaxed and slack, but still professing the Catholic doctrine – resolved to correspond to grace in the end. Thus not only the good priests, but also the lukewarm ones, became great martyrs. This reminds me of the Good Thief who did not deserve it, but who was chosen by divine mercy and rose to a high place in Heaven.

You see how encouraging this is for us, giving us the hope that when the great events predicted by Our Lady in Fatima will take place, we can be faithful as well. Instead of viewing the coming chastisement with terror, we should consider it as an occasion for great graces. That will be one of those moments when Divine Providence calls together its good and relapsed sons, even the sons with whom it was displeased. At that moment, as in the French Revolution, by marvels of grace the martyrdom and the honors of the altar will become accessible to people who, according to the natural order of things, would never have reached this glory or perhaps would even be in hell.

Here is another aspect of the plan of Providence that shows how God is admirable in the harmonic oppositions – but not contradictions – of His works. On one hand, He is admirable in making those estimable Carmelite martyrs of Compiègne – who were so well prepared – rise to Heaven. On the other hand, He is admirable in making saints of faithful priests as well as lamentably unfaithful priests who, placed before the supreme test of betrayal or death, assisted by grace and against the plans of human prudence, ended by preferring death, preferring martyrdom.

Let us ask all those martyrs to pray for us. We ask those who were always faithful to help us become as entirely faithful as the Carmelites of Compiègne. And from those who were not faithful, we ask that, should we not be entirely prepared, we might benefit from that same mercy that they themselves received.

1 - On July 17, 1794, a group of Carmelite nuns in Compiègne were guillotined by the revolutionaries. The German novelist, Gertrud von le Fort (1876-1971), wrote an historical novel about this episode that was later adapted for theater by Georges Bernanos (1888-1948 ) under the title Dialogue of the Carmelites, which was published after his death in 1949. Prof. Plinio is referring to this episode.

| | Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|