|

The Saint of the Day

St. Stephen Harding – April 17

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Biographical selection:

St. Stephen Harding, right, and the Benedictine Abbot of St. Vaast, left, present models of their churches to Our Lady - Bibliotheque Municipal Dijon

|

Stephen Harding, son of an English noble, consecrated himself very early to the monastic life in the Abbey of Sherbonne in Dorsetshire. He was sent to France and pursued a brilliant course in humanities, philosophy and theology.

After a pilgrimage to Rome, he returned to France to the Abbey of Molesme, under the direction of the Abbot St. Robert and Blessed Alberic. Notwithstanding the influence of these saints, the monastery declined. The two saints determined to leave the community and together with St. Stephen and 18 other monks, they instituted a reformed new abbey in Cîteaux (Cister) with the support of Duke Eudes of Bourgogne. This was the origin of the famous Cistercians. On Alberic’s death in 1110, St. Stephen was elected Abbot of the monastery and wrote its statutes, which were approved by Pope Paschal II.

During his term as Abbot, St. Stephen fought to maintain the strict observance. Since the monastery received very few novices, he began to have doubts that the new institution was pleasing to God. He prayed for enlightenment and received a response that encouraged him and his small community. From Bourgogne a noble youth arrived with 30 companions, asking to be admitted to the abbey. This noble was the future St. Bernard. In 1115 St. Stephen built the abbey of Clairvaux, and installed St. Bernard as its Abbot. From it 800 abbeys were born.

St. Stephen died in 1134, saying that he would appear before God as a useless servant who had made poor use of the gifts God had given him.

Comments of Prof. Plinio:

The life of St. Stephen shows us the various ways grace works regarding religious orders. Each of them is gifted in its origins with the needed graces to fulfill the mission it received from God. In general, in the first phase, an order accomplishes its mission. This phase often coincides with the heroic phase of the founder, grand accomplishments, and great saints.

At a certain moment, as is common with things human, the religious order enters into a period of decline. Then either additional saints communicate a new impulse to it, or it continues to slowly deteriorate. As it declines, there is an option: either it closes or it gives birth to new branches. When a new branch is formed, it shines with a brilliance that equals the splendor of the order's first days. The trunk is invigorated by the new growth and continues to live.

Why does God allow certain orders to die and others to have their existence wonderfully prolonged by a glorious continuity?

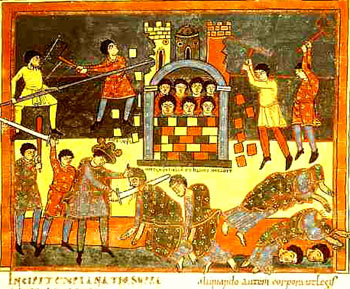

The Carmelites will last until the end times,

when the Antichrist will slay Elias and Enoch

|

To consider only one aspect of the matter, there are certain religious orders that have a perennial role in the Catholic Church. They irradiate a certain spirit that is indispensable to the Church. It is a perfume that God wants His Church to have since it is a part of her very physiognomy. So God conserves those religious orders that maintain these characteristics. Other religious orders, however, which God judges as not indispensable to the Church, decline and disappear.

Among the orders in the first category, none has so wonderful a continuity as the Order of Carmel. According to a very respectable tradition, it was founded by Elias the Prophet, that is to say, long before the birth of Our Lord. It passed through trials and sufferings, brilliant successes and great failures until the coming of St. John the Baptist, who would be a member of this spiritual family and the greatest successor of Elias. Our Lord Himself would have been close to those religious, who for a certain period would be part of the movement of the Essenes.

Then, with the New Covenant and the dispersion of the Hebrew people, the Order took the name it has today and remained at Mount Carmel until the Muslim persecutions obliged it to flee to the West. In Europe it was at the point of closure when Our Lady appeared to St. Simon Stock – who was the General of the Order – and gave him the scapular devotion. With this, a torrent of graces came to the Order.

Later, St. Teresa of Ávila and St. John of the Cross reformed a part of the Carmelite Order. This branch of reform influenced the whole trunk, and it continued to shine until it produced one of its most beautiful flowers, which was St. Therese of Lisieux. Afterward, a phenomenon of general decay set in until it experienced the tornado of bad consequences coming from Vatican, which we know.

You see that Divine Providence wants to conserve the Order of Carmel. According to private prophecies, this Order will never disappear. It will continue – from one glory to another and one trial to another – until the moment that its founder, Elias the Prophet, will return and be present in the last days of History to fight against the Antichrist, who will kill Elias. Then he will be resurrected, and see the return of Our Lord Jesus Christ for the Final Judgment.

There is, therefore, a mystery of predilection of Our Lady for this spiritual family. For this reason, it has greater longevity than other orders.

One finds a similar action of Divine Providence with regard to the oldest Western order, the Benedictine Order. St. Benedict is the Patriarch of the Western monks. All of Western monasticism was born from him. He founded a religious order that spread throughout Europe and worked the conversion of the barbarians in one of the worst moments of the Church’s History.

Paradoxically, the Church at this time was contaminated by the germs of corruption of the pagan world that she had helped to destroy. On one hand, the spirit of softness and sensuality of Paganism survived in many ecclesiastics and lay faithful. On the other hand, the Church had to face the barbarian invasions. For the most part, the barbarians were heretics; they were partisans of Arianism. That is to say, the Church had enemies both inside and outside.

In this crucial situation, the Benedictine monks entered the scenario and worked for the conversion of the barbarians. The conversion of England, Ireland, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Bohemia, Austria, and Hungary was due in great part to the work of the Benedictine Order. Its monks worked in a way that brought them much prestige.

What did they do? The modern missionary runs after the unfaithful and tries to convert him. The Benedictine missionary did not do this. He would go to an area without the Faith and found an abbey there. The abbey would begin its monastic life of praying and chanting the Divine Office and, at the same time, it would give alms to the poor, systematically work the lands, drain the swamps, and civilize the land surrounding the abbey. Because of the good example of the Benedictines in these different spheres, the Order exerted an enormous influence on souls. The surrounding villages would start to depend on the abbey. Sometimes populations would build towns and even cities around the abbeys.

Monks pray and harvest crops - Joerg Breu the Eldern

|

So, the apostolate of the Order was to attract by its way of being. The people used to come to the Benedictine, and not the Benedictine to the people. I think it is a beautiful way to attract souls – they lived their own life, radiating their particular luster and diffusing the perfume of the lives they led.

While some branches of the Benedictine Order were converting the barbarians, others were preparing the ground for the Middle Ages. All the spiritual, cultural, artistic, political and military development of the Middle Ages relied in great part on the Benedictines. Some historians sustain that the Spanish Reconquista relied on the Benedictines of Cluny, others present good arguments that the Holy Roman-German Empire would not even have been possible without Cluny. Cluny was not, properly speaking, a new branch. It was a movement inside the Order that gave new life to it. After some time, the Benedictines of Cluny also fell into decay.

Then, Divine Providence called on an English noble, who entered a declining Benedictine abbey and met two other saints who were fighting against the decadence. They left that abbey and founded another branch with a stricter discipline. It was so small and lacking in vocations that even St. Stephen had a doubt whether its foundation was really the will of God. He asked for a sign from Heaven.

Smiling, Our Lady, Mother of all the good initiatives in the Church, gave him a most beautiful sign. It was the arrival of a knight, the future St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who was accompanied by 30 companions. They came and asked to enter the new abbey.

The arrival of St. Bernard was no small thing. He is one of the suns of the Benedictine Order, one of the greatest devotees of Our Lady called the Doctor Mellifluus – the doctor who speaks on Our Lady with the sweetness of honey (from the Latin mel = honey). He was a man of penance and mortification, a polemicist and a fighter who faced hard combats against all the enemies of the Church at his time. One of them was Peter Abelard, a very bad man who I consider to be a precursor of Progressivism.

Above, models of Cluny at its height 1088-1130. Below, Cluny today. Only the main tower survived the destruction of the French Revolution

|

With his 30 knights St. Bernard gave splendor to the new branch of the Benedictine Order, which in its turn brought new life and vigor to the ensemble. It was a new aspect of the same vocation. What did this branch do? Complete silence, manual work, study, cloister. The life of cloister was only broken when the monks had to travel to preach a mission.

They differed from the old Benedictine in this way of preaching missions. They also had a different habit. The Cistercians have a white habit with a black scapular, while the Benedictines have a black habit. The Cistercians practiced greater poverty than the Benedictines, their churches were simpler and more austere with simple stain glass. That poverty was necessary to correct the abuses produced by the former richness.

Step by step many branches of the Benedictine family recovered their fervor. The branch of Cluny, however, did not recover. It continued to decay until the French Revolution when the abbey of Cluny itself was destroyed. Almost nothing of the main building remained. The wrath of God fell over that institution and it was razed. Some buildings of the complex still exist, the relics of the founders remain in the city of Cluny, but the main part of the enormous abbey disappeared.

This is a quick overview on how Divine Providence acts with religious orders. It answers the question why some orders disappear and other remain. It also gives the examples of two great orders, the Order of Carmel, which will remain until the last days, and the Benedictine Order. Inside the Benedictine family, we saw how the Cistercians became a new branch that brought fresh life to the ensemble.

These are some considerations inspired by the excerpt on the life of St. Stephen Harding, founder the Cistercian branch of the Benedictine Order. Let us ask him to protect us and teach us how to confide in the plans of Divine Providence even against all appearances of failure, as he did before the coming of St. Bernard and his knights.

| | Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira | |

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church. TIA thought that its readers could profit from these valuable commentaries.

The texts of both the biographical data and the comments come from personal notes taken by Atila S. Guimarães from 1964 to 1995. Given the fact that the source is a personal notebook, it is possible that at times the biographic notes transcribed here will not rigorously follow the original text read by Prof. Plinio. The commentaries have also been adapted and translated for TIA’s site.

|

Saint of the Day | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|