Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Obligation of Subsidiarity

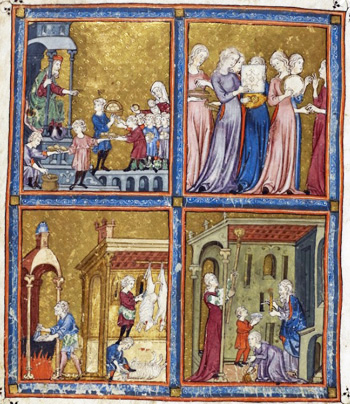

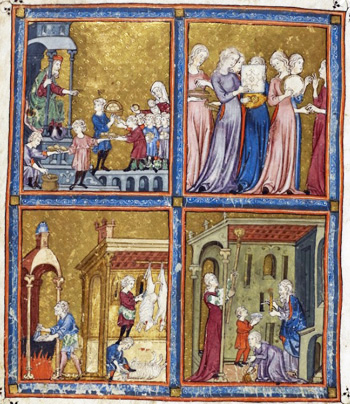

Let us consider the social intermediary groups that existed between the state and the individual in the pre-revolutionary European nations, which formed a powerful ensemble of organic societies. If the contemporary man would have an exact notion of what was a region, a fief, a municipality, a large autonomous guild etc. in the context of an organic society, he would greatly enrich his premises. These premises in turn would help to make discussions on the forms of governments gain in clarity, strength and practical fruit.

Organic society is a topic that should be considered opportune, given that the attempts to merge Europe into a single social-political-military-economic entity have resulted in a surge of exacerbated nationalisms and centralisms, which the media reports as ships sailing without a rudder or compass in a tumultuous sea of indecision. From this fundamental deficiency comes a lamentable weakness of understanding that threaten to end the whole.

Underlying this topic is an elevated principle of wisdom that gives the person who knows it a perfect knowledge of what he should do. A man may have the knowledge, power and authority; nonetheless many times he allows the action to be taken by the intermediary. At times things are not done due to the inaction of the intermediary, yet the higher authority does not intervene. There is a principle of wisdom in this way of proceeding.

Underlying this topic is an elevated principle of wisdom that gives the person who knows it a perfect knowledge of what he should do. A man may have the knowledge, power and authority; nonetheless many times he allows the action to be taken by the intermediary. At times things are not done due to the inaction of the intermediary, yet the higher authority does not intervene. There is a principle of wisdom in this way of proceeding.

The principle of subsidiarity is characterized by this: When man cannot realize by his own means what is necessary for him to do or have, he should be helped by those who are closer to him. If there is no one closer, anyone who observes that need is obliged to help him.

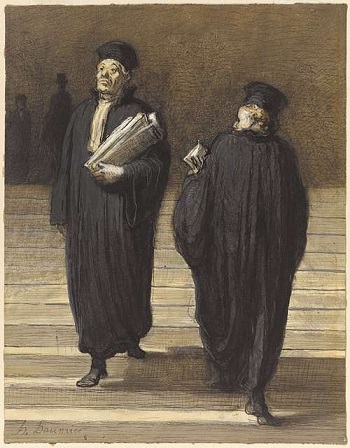

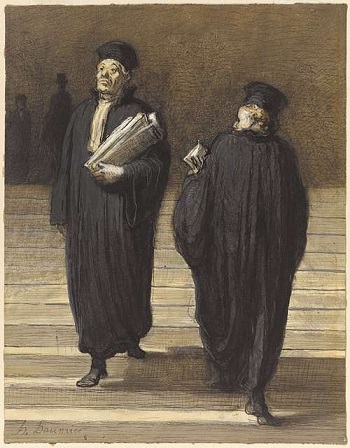

We can imagine two lawyers who have their offices on the same floor of a building. They are colleagues and know each other well. Lawyer A has prodigious talent and his waiting room is always filled with clients. At the other end of the hallway is the office of lawyer B, who is less brilliant, learned and intelligent. Therefore, he is only asked to defend small cases, while the better clients take their great cases to lawyer A.

Now then, lawyer A knows that lawyer B is a good man with a family but can barely provide for them to live with dignity. What should lawyer A do? He has the obligation to give lawyer B some of his clients, provided of course that he believes that lawyer B is capable of executing the work well.

This is not a pure act of charity or friendship between colleagues; he has the obligation to do this.

Seeing one who does not have the means to provide for his needs, the others around him have the obligation to come to his assistance. There should be a certain order, a certain hierarchy, in the provision of this aid: The ones who are closer to the person in need have a more immediate obligation, those further from him have a less immediate duty. In principle, however, any person has an obligation in relation to another who is in need.

Seeing one who does not have the means to provide for his needs, the others around him have the obligation to come to his assistance. There should be a certain order, a certain hierarchy, in the provision of this aid: The ones who are closer to the person in need have a more immediate obligation, those further from him have a less immediate duty. In principle, however, any person has an obligation in relation to another who is in need.

It was for this reason that I imagined the two lawyers working on the same floor of the building, let us suppose the first floor. Now let us consider that there is a lawyer C in the same difficult situation as lawyer B, but working on the top floor of the building. In such case lawyer A should only help lawyer C after having helped lawyer B in his essential needs. After that, he should also send some clients to lawyer C.

The proximity of offices, however, should not prevail over other more important factors. For example, let us suppose that lawyer C were a distant relative of lawyer A. In this hypothesis, lawyer A should help lawyer C first, because the relationship of relatives is more important than the physical proximity of offices. There is a hierarchy in this obligation.

If lawyer A and lawyer C were Catholics and lawyer B were not a Catholic, lawyer A should help lawyer C first, because the closeness between two members of the Catholic Church is more than distant family links or the physical proximity of offices.

The man in need should be helped because he cannot provide for himself without any personal blame. It is not because he is lazy or does not study or does not do his job well; it is because he has no personal blame for his situation.

Further, the man in need does not have to be in a situation of extreme poverty, but rather in a situation in which he lacks what is necessary to live.

Here we have the principle of subsidiarity. This should be enough to define it. It naturally generates a whole series of hierarchies, because the one who receives should also be grateful to the one who gives.

Thus, the action of the giver falls on the beneficiary like the water that falls from a fountain to its basin, and the splashes that rise upward from the basin are the expressions of gratitude of the beneficiary.

Posted June 4, 2025

Organic society is a topic that should be considered opportune, given that the attempts to merge Europe into a single social-political-military-economic entity have resulted in a surge of exacerbated nationalisms and centralisms, which the media reports as ships sailing without a rudder or compass in a tumultuous sea of indecision. From this fundamental deficiency comes a lamentable weakness of understanding that threaten to end the whole.

The needy should be helped

so that they might live with self-dignity

The principle of subsidiarity is characterized by this: When man cannot realize by his own means what is necessary for him to do or have, he should be helped by those who are closer to him. If there is no one closer, anyone who observes that need is obliged to help him.

We can imagine two lawyers who have their offices on the same floor of a building. They are colleagues and know each other well. Lawyer A has prodigious talent and his waiting room is always filled with clients. At the other end of the hallway is the office of lawyer B, who is less brilliant, learned and intelligent. Therefore, he is only asked to defend small cases, while the better clients take their great cases to lawyer A.

Now then, lawyer A knows that lawyer B is a good man with a family but can barely provide for them to live with dignity. What should lawyer A do? He has the obligation to give lawyer B some of his clients, provided of course that he believes that lawyer B is capable of executing the work well.

This is not a pure act of charity or friendship between colleagues; he has the obligation to do this.

A successful lawyer should help a unsuccessful colleague following certain priorities

It was for this reason that I imagined the two lawyers working on the same floor of the building, let us suppose the first floor. Now let us consider that there is a lawyer C in the same difficult situation as lawyer B, but working on the top floor of the building. In such case lawyer A should only help lawyer C after having helped lawyer B in his essential needs. After that, he should also send some clients to lawyer C.

The proximity of offices, however, should not prevail over other more important factors. For example, let us suppose that lawyer C were a distant relative of lawyer A. In this hypothesis, lawyer A should help lawyer C first, because the relationship of relatives is more important than the physical proximity of offices. There is a hierarchy in this obligation.

If lawyer A and lawyer C were Catholics and lawyer B were not a Catholic, lawyer A should help lawyer C first, because the closeness between two members of the Catholic Church is more than distant family links or the physical proximity of offices.

The man in need should be helped because he cannot provide for himself without any personal blame. It is not because he is lazy or does not study or does not do his job well; it is because he has no personal blame for his situation.

Further, the man in need does not have to be in a situation of extreme poverty, but rather in a situation in which he lacks what is necessary to live.

Here we have the principle of subsidiarity. This should be enough to define it. It naturally generates a whole series of hierarchies, because the one who receives should also be grateful to the one who gives.

Thus, the action of the giver falls on the beneficiary like the water that falls from a fountain to its basin, and the splashes that rise upward from the basin are the expressions of gratitude of the beneficiary.

Posted June 4, 2025

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Prof. Plinio

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the transcripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

______________________

______________________