Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Medieval Written Law - III

Dynamism of the Associative Principle &

The Salutary Right to Resist

The analyses of the different kinds of laws in the previous articles (Part I and Part II) lead us to study the life inside and outside of the fief, as well as the authority of the feudal lord, so that we can properly understand feudal law.

The associative principle was extraordinarily dynamic in the Middle Ages. This gave rise to the establishment of multiple associations, which were called universities. These were not only universities of study, as we know them today, composed of an ensemble of schools of higher learning, but the word university encompassed any corporation, association or juridical person. (1)

The associative principle was extraordinarily dynamic in the Middle Ages. This gave rise to the establishment of multiple associations, which were called universities. These were not only universities of study, as we know them today, composed of an ensemble of schools of higher learning, but the word university encompassed any corporation, association or juridical person. (1)

Today we create an association when a number of individuals meet, record minutes of the meeting and enlist the organization in the civil register. At that time an association was created by an act of the king or the feudal lord, and by means of that act the juridical person was constituted.

But, since the ruling principle in all of Medieval Law was that the functions of the State should be delegated to private individuals, as soon as the king or feudal lord constituted a university, he would delegate a part of his own political power to that organism. In this way, the university would be able to make the laws for its members.

Thus, the majority of the legislation for labor, which today is generated by the State, was made by private individuals in the Middle Ages. The corporations or universities of professionals would compose most of the laws for their own members.

Here we have, then, another type of law, very limited, which governed small groups and was made by minor authorities. This was another type of legislative thread that weaved the legal fabric of a medieval nation.

How could an individual defend himself against the State?

Now let us consider another point. What was the defense of a medieval man against the State?

I place the question with an example. During the 18th century in Portugal the Marquis of Pombal, who was the equivalent of a Prime Minister of King José I, was spreading the ideas of Enlightenment and quashing the organic nobility. With the aim of oppressing the nobility, he decided to attack the House of the Marquis of Távora, whose family was the intermediary link between the Royal Family and the rest of the Portuguese nobility. The Távoras were close to the House of the Dukes of Aveiro, which was also a great House.

Pombal fabricated an assault against King José I when he was riding incognito in a carriage through Lisbon at night and accused the Távoras of committing that crime to kill the King and replace the Royal House with the House of Aveiro. There was no evidence for the accusation; notwithstanding, he imprisoned the entire family, condemned most of them to death for the crime of lèse-majesté.

Pombal fabricated an assault against King José I when he was riding incognito in a carriage through Lisbon at night and accused the Távoras of committing that crime to kill the King and replace the Royal House with the House of Aveiro. There was no evidence for the accusation; notwithstanding, he imprisoned the entire family, condemned most of them to death for the crime of lèse-majesté.

He executed them, took possession of their properties and destroyed their palaces. The House of the Dukes of Aveiro also suffered a great persecution under the same accusation. The confessor of the Távoras, Fr. Gabriel Malagrida, a Jesuit, was burned at the stake, and simultaneously Pombal expelled the Jesuit Order from Portugal and confiscated its properties.

Now, I ask: If one of us would have been the Marquis of Távora and would have known that a Freemason, an iniquitous minister, was plotting to destroy our family, our history, our traditions, and all those privileges amassed for centuries in our House, and further, that the final aim of that minister was to destroy what was left of the old nobility of Portugal, what should he have done? What kind of action should the head of the Távora family have taken?

Should he have fled to live like a beggar in a foreign country? If he fled, he would be implicitly acknowledging as true the accusations against him. Should he have resisted? But how should he resist? Should he have taken his case before the tribunals? But in the dictatorship of Pombal, all the courts were blindly obedient to him.

Here we have the problem that I want to focus on. In Medieval Law there was a way to resist an unfair decision of a superior, be he a king, a feudal lord or a powerful minister, that no longer existed in the absolutist States of the 18th century.

All medieval society was constructed based on private contracts. It was through a contract that the king would offer a part of his patrimony to a vassal. That contract would define both the rights of the king and those of the vassal. Based on that contract, the noble vassal would further divide what he had received and transfer part of it to his inferiors through similar contracts. The same procedure would be followed all the way down to the bottom rungs of the nobility.

The king and the feudal lords would take similar actions with each city by means of contracts. It is common to find charters of that time favoring this or that city. Sometimes they would make a city autonomous through a contract.

All of society was formed by contracts establishing the rights and duties of each of the parties involved, from top to bottom.

The right to an armed resistance

What was the practical result of this chain of contracts?

The king, the vassals, the cities and all other political units each had their own soldiers and weapons. That is, they had the means to ensure the enforcement of the contracts in face of transgressions by the other party. Thus, logically, when one of the parties would violate the rights and duties established by contract, the other party would become exempt from its obligations.

When the violation of the obligations was made by the inferior, he would be considered a felon, and this crime of felony was one of the most censured by medieval morality. Felony was the crime of the vassal, and one can find many cases in medieval annals of the punishment meted out to vassals for their felonies.

On the other hand, when the rupture of the contract was made by the superior party, as the numerous cases of abuses by kings, then the nobles would stand up against the king, making an armed resistance. They would make an armed resistance and no one would consider this a felony. It was perfectly natural: There was a contract, the superior violated it, the inferior made an armed resistance to defend himself.

When we place ourselves before this perspective, it can seem chaotic. Corporations, municipalities, fiefs all making armed resistances against the king would appear to lead to political chaos. If each one can make an armed resistance when he imagines he has the right to do so, each one is the judge of his own situation; the result seems to be chaos.

If we transfer this principle to today’s society and we imagine that each head of an industry or an owner of a house of commerce, a farmer, a mayor of a city, or a governor of State would have the right to make an armed resistance, then the State would cease to exist.

It is true that this legitimate position that governed in the Middle Ages is full of dangers, since each time that a man has to judge his own rights, he can commit an abuse.

It is true that this legitimate position that governed in the Middle Ages is full of dangers, since each time that a man has to judge his own rights, he can commit an abuse.

Does this mean that the principle is false? I do not think so. Let us imagine that one of us is unjustly condemned to death. The police comes to this hall to haul him to prison. He has the right to make an armed resistance. This is not absurd because he is innocent and he has the right to self-defense.

Further, if the State makes an unjust law contrary to Natural Law, I have the right to resist and formally disobey the State. I have the right to judge according to Natural Law whether that State law is just or unjust. This is Catholic doctrine.

One could say that I am going too far by imagining that I have the right to judge the State. I would ask: Is not an abuse of the State, that does not give the right to its subordinates to control its actions, a very serious abuse?

Let us look, for example, at the time of the absolute monarchy, before the French Revolution. The King legislated; the clergy, nobles and bourgeoisie bowed before the King. Apparently, a splendid order reigned, if we understand order as the absence of social turbulence. No one rose up. Everything was calm. In this sense, we could say that the place in a city where the greatest order reigns was in its cemetery: No one moved no one made any protest or uprising.

If this absolute inertia is what we understand by order, then the absolutist State was in good order. The State could do whatever it liked without any resistance. From this state of affairs came the artificial society that was the French society prior to the French Revolution. The nobility did not have any defined function; the clergy was degraded by the action of the King; the plebeians were on the brink of disappearing. There was an absolute order: No one revolted, no one stood up against abuses.

Now, let us compare this situation with the apparent turbulence of the Middle Ages. There was much more agitation, but each one knew how to make his rights respected. It was not an extremely tranquil and well combed social order, but it had the proper movement of a living body. Each class reacted when it was wounded or stepped on. The result was many concrete fights, a multitude of judicial battles. But since everyone defended himself, everyone ended by finding his own place.

It was a society where almost everyone could live without his rights being trampled, based on the contractual character of the Middle Ages.

Continued

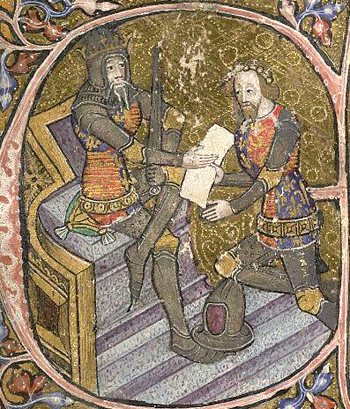

King Edward III sealing a contract with the Black Prince

Today we create an association when a number of individuals meet, record minutes of the meeting and enlist the organization in the civil register. At that time an association was created by an act of the king or the feudal lord, and by means of that act the juridical person was constituted.

But, since the ruling principle in all of Medieval Law was that the functions of the State should be delegated to private individuals, as soon as the king or feudal lord constituted a university, he would delegate a part of his own political power to that organism. In this way, the university would be able to make the laws for its members.

Thus, the majority of the legislation for labor, which today is generated by the State, was made by private individuals in the Middle Ages. The corporations or universities of professionals would compose most of the laws for their own members.

Here we have, then, another type of law, very limited, which governed small groups and was made by minor authorities. This was another type of legislative thread that weaved the legal fabric of a medieval nation.

How could an individual defend himself against the State?

Now let us consider another point. What was the defense of a medieval man against the State?

I place the question with an example. During the 18th century in Portugal the Marquis of Pombal, who was the equivalent of a Prime Minister of King José I, was spreading the ideas of Enlightenment and quashing the organic nobility. With the aim of oppressing the nobility, he decided to attack the House of the Marquis of Távora, whose family was the intermediary link between the Royal Family and the rest of the Portuguese nobility. The Távoras were close to the House of the Dukes of Aveiro, which was also a great House.

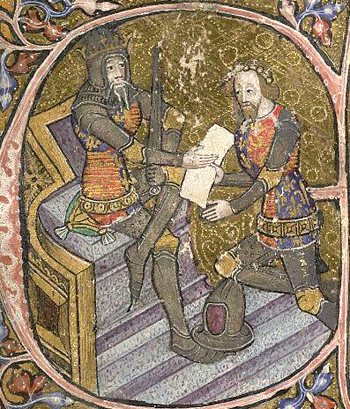

The despotic Marquis de Pombal ruined

the nobility & the clergy in Portugal

He executed them, took possession of their properties and destroyed their palaces. The House of the Dukes of Aveiro also suffered a great persecution under the same accusation. The confessor of the Távoras, Fr. Gabriel Malagrida, a Jesuit, was burned at the stake, and simultaneously Pombal expelled the Jesuit Order from Portugal and confiscated its properties.

Now, I ask: If one of us would have been the Marquis of Távora and would have known that a Freemason, an iniquitous minister, was plotting to destroy our family, our history, our traditions, and all those privileges amassed for centuries in our House, and further, that the final aim of that minister was to destroy what was left of the old nobility of Portugal, what should he have done? What kind of action should the head of the Távora family have taken?

Should he have fled to live like a beggar in a foreign country? If he fled, he would be implicitly acknowledging as true the accusations against him. Should he have resisted? But how should he resist? Should he have taken his case before the tribunals? But in the dictatorship of Pombal, all the courts were blindly obedient to him.

Here we have the problem that I want to focus on. In Medieval Law there was a way to resist an unfair decision of a superior, be he a king, a feudal lord or a powerful minister, that no longer existed in the absolutist States of the 18th century.

All medieval society was constructed based on private contracts. It was through a contract that the king would offer a part of his patrimony to a vassal. That contract would define both the rights of the king and those of the vassal. Based on that contract, the noble vassal would further divide what he had received and transfer part of it to his inferiors through similar contracts. The same procedure would be followed all the way down to the bottom rungs of the nobility.

The king and the feudal lords would take similar actions with each city by means of contracts. It is common to find charters of that time favoring this or that city. Sometimes they would make a city autonomous through a contract.

All of society was formed by contracts establishing the rights and duties of each of the parties involved, from top to bottom.

The right to an armed resistance

What was the practical result of this chain of contracts?

The king, the vassals, the cities and all other political units each had their own soldiers and weapons. That is, they had the means to ensure the enforcement of the contracts in face of transgressions by the other party. Thus, logically, when one of the parties would violate the rights and duties established by contract, the other party would become exempt from its obligations.

When the violation of the obligations was made by the inferior, he would be considered a felon, and this crime of felony was one of the most censured by medieval morality. Felony was the crime of the vassal, and one can find many cases in medieval annals of the punishment meted out to vassals for their felonies.

On the other hand, when the rupture of the contract was made by the superior party, as the numerous cases of abuses by kings, then the nobles would stand up against the king, making an armed resistance. They would make an armed resistance and no one would consider this a felony. It was perfectly natural: There was a contract, the superior violated it, the inferior made an armed resistance to defend himself.

When we place ourselves before this perspective, it can seem chaotic. Corporations, municipalities, fiefs all making armed resistances against the king would appear to lead to political chaos. If each one can make an armed resistance when he imagines he has the right to do so, each one is the judge of his own situation; the result seems to be chaos.

If we transfer this principle to today’s society and we imagine that each head of an industry or an owner of a house of commerce, a farmer, a mayor of a city, or a governor of State would have the right to make an armed resistance, then the State would cease to exist.

Juridical and armed disputes were the healthy consequences of the right of self defense

Does this mean that the principle is false? I do not think so. Let us imagine that one of us is unjustly condemned to death. The police comes to this hall to haul him to prison. He has the right to make an armed resistance. This is not absurd because he is innocent and he has the right to self-defense.

Further, if the State makes an unjust law contrary to Natural Law, I have the right to resist and formally disobey the State. I have the right to judge according to Natural Law whether that State law is just or unjust. This is Catholic doctrine.

One could say that I am going too far by imagining that I have the right to judge the State. I would ask: Is not an abuse of the State, that does not give the right to its subordinates to control its actions, a very serious abuse?

Let us look, for example, at the time of the absolute monarchy, before the French Revolution. The King legislated; the clergy, nobles and bourgeoisie bowed before the King. Apparently, a splendid order reigned, if we understand order as the absence of social turbulence. No one rose up. Everything was calm. In this sense, we could say that the place in a city where the greatest order reigns was in its cemetery: No one moved no one made any protest or uprising.

If this absolute inertia is what we understand by order, then the absolutist State was in good order. The State could do whatever it liked without any resistance. From this state of affairs came the artificial society that was the French society prior to the French Revolution. The nobility did not have any defined function; the clergy was degraded by the action of the King; the plebeians were on the brink of disappearing. There was an absolute order: No one revolted, no one stood up against abuses.

Now, let us compare this situation with the apparent turbulence of the Middle Ages. There was much more agitation, but each one knew how to make his rights respected. It was not an extremely tranquil and well combed social order, but it had the proper movement of a living body. Each class reacted when it was wounded or stepped on. The result was many concrete fights, a multitude of judicial battles. But since everyone defended himself, everyone ended by finding his own place.

It was a society where almost everyone could live without his rights being trampled, based on the contractual character of the Middle Ages.

Continued

- In Portuguese and other Latin languages, a juridical person is any ensemble of individuals who associate together to pursue a determined goal and are recognized as such by the civil authority. Thus, any social entity is a juridical person with its rights and duties. The simple individual is designated as a physical person, with his rights and duties. Law considers each of these categories separately: physical and juridical persons.

Posted February 20, 2015

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Prof. Plinio

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the transcripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

______________________

______________________