|

Organic Society

The Bourgeois in Free Cities and Kingdoms

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

The dignity of the bourgeois lies in security, and his goal is not to shine as a noble in the whole society or the State government but, rather, to stand out in smaller, local circles.

In learned circles when people speak about the bourgeoisie in the Ancien Regime, the data they present are insufficient. They usually start by comparing the bourgeoisie of that period with the aristocracy, describing contrasts between the two classes. Such a presentation leaves the bad taste of a Marxist class struggle in one's mouth. This biased history does not offer a fair exposition of the way society was organized at that time.

Certainly one may compare the classes in the second stage of a study, but first he should ask: What role does each one play in society and the State? We will try to answer this question with regard to the bourgeoisie. I begin by distinguishing between two different bourgeoises, or two different situations of the bourgeoisie.

The bourgeoisie in autonomous cities

In one case, the bourgeoisie was the first class of society, when it was the governing class of free cities - at times sovereign free cities – or when it governed local groups that enjoyed a strong autonomy in relation to the State. The bourgeoisie would appear as an eminent class in such places, although it maintained its bourgeois characteristics.

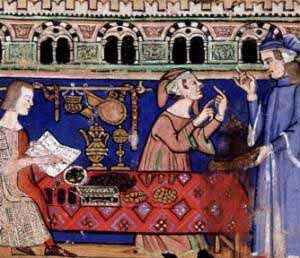

Antwerp was a center of intense commerce |

We find this, for example, in two medieval cities of Flanders: Bruges and Antwerp. Those cities were important ports with intense movements of commerce that generated a great wealth. Bruges was in the territory of the County of Flanders and Antwerp part of the Duchy of Brabant. Some nobles of those houses were probably much less prosperous than the leading bourgeois families of those cities.

Nonetheless, the noble was superior to the bourgeois. Why? Was the bourgeois greater in some regards and lesser in others? Was he considered more important than the noble? Under what circumstances, and why? These questions in themselves reveal different aspects of the matter that we must take into consideration in order to analyze the bourgeoisie.

It is curious to note that the bourgeoisie as the first class of society developed principally in the Kingdom of Lothar (795-855), the grandson of Charlemagne, whose domains extended from the Netherlands into Italy, down to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples). I am not sure why, but the Kingdom of Lothar produced innumerable small autonomous cities. We find far fewer of these free cities in Spain and Portugal – where, by the way, the cities had many privileges but were not autonomous – and a few of them in France, but they did not last long there. Germany also had many such cities, especially in Franconia and Swabia, but they originated in a different way, at a time when Germany was generating small, independent political units.

The bourgeoisie in Kingdoms

The second case is a bourgeoisie situated inside a homogenous State or Kingdom, and not an autonomous city. Here, the bourgeoisie constituted part of an ensemble in which it played a specific mediating role, having other classes above it, below it and at its same level.

In a Kingdom, the bourgeois had to respect the established social hierarchy |

What were the characteristics of a bourgeois in a city like Paris? We may say that, excluding professions that competed with the Clergy (such as teaching) and those that competed with the nobility (State government and military functions), the other professions were made up of manual workers. All of these extremely diversified professions formed the bourgeoisie. There were manual workers and craftsmen of various kinds.

Those who were not manual workers held offices in the municipal government, e.g., the judges, public magistrates and bookkeepers. Yet others served public functions, such as the notaries, tax collectors and local police officers. Some exerted public influence as teachers or artists, and the men of commerce also would achieve some degree of social prestige and influence.

We see that what distinguished the bourgeois from the noble was not principally the function he exercised in society, but his spirit and the way he did it. Function could play a role in generating the noble mentality, but what characterized the noble was the possession of a certain state of spirit.

Dedication and risk, characteristics of the noble

Generally speaking, who was noble in Europe? Nobles were those men who shared the land with the King. They lived as owners of that land and ruled over it as baron, viscount, count, etc. They also had the obligation to defend it, as well as the other lands of the King with their own blood against any adversary.

These obligations presupposed that the noble would have a taste for heroism, adventure and the military condition, which would shape his spirit in a special way. This superior spirit would lead him to be turned toward dedication, prepared for adventure, in search of excellence and magnificence, and open to the sublime. A man nurtured in this ambience would consider it very worthwhile to give his life to fulfill his duty and earn glory for God and his name. For him, such glory was an advantage worth dying for. Of course, this notion of glory cannot be completely understood unless one has the Catholic belief in Heaven.

For these nobles, the pleasure of life was not luxury, but to stand at the brink of danger and adventure and to revel in the beauty of total dedication to the defense of the honor of their name or their King, or some other superior cause.

The pleasure to face risks at the service of his Faith and King was a characteristic of the noble |

These qualities would give a splendorous, almost mythic character to the government and command of a noble.

This constant dedication to a superior cause gave the noble both a right and a need: The right and the need to live in a splendid way corresponding to that glorious generosity. For this reason, the noble had a different way of dressing. For a noble to dress as a bourgeois was tantamount to a priest dressing as a layman. The priest’s garb was a reflection of his religious dedication – the vows he made to serve the Faith, to win Heaven, to give testimony to the transitory nature of the goods of this earth, etc. Analogously, the dressing of the noble should be splendid.

He should have refined manners, use a distinguished language, have a magnificent décor. The excellence surrounding the noble should be an expression of that fundamental sense of sacrifice that his life represented. He was a man surrounded by glory in constant readiness for martyrdom. Not the martyrdom of the first Catholics in the arena, but the martyrdom of the Crusader who died destroying the enemies of our Faith.

In the French Revolution the nobles still had the heroism to die, but not to die killing the enemy. They went to their death without a fight. This was a great decadence. Many had very beautiful deaths, but they were no longer willing to give battle against those revolutionaries. It was legitimate for nobles to leave France and seek refuge in Belgium and other neighboring countries, but it was not much different from an escape.

Therefore, the essence of the noble spirit is the spirit of risk and militancy.

The bourgeois does not have this spirit

No one can deny that the risk of losing money does not have the same excellence as the risk of losing one’s life. Taking a financial risk can demand boldness, but not virtue or heroism. Courage is only praiseworthy when a person does something indispensable for a higher cause. No one has the right to risk himself without good reason.

Regarding money, normally speaking, there is no reason to take great risks. When a man has the obligation to assure the continuity of a family or a business, then risk is not a right, but rather something to be avoided. The typical bourgeois looks for stability and the needed security to achieve it. Then, once he attains it, he looks for material comfort.

The spirit of a bourgeois, therefore, is essentially different from that of a noble. It is this spirit – more than a function in society – that must be studied when one addresses the bourgeoisie.

Posted February 22, 2010

| | Prof. Plinio |

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the trancripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

Related Topics of Interest

The Healthy Rise of the Bourgeoisie The Healthy Rise of the Bourgeoisie

All Classes Should Have Elites All Classes Should Have Elites

The City and Its Nobility The City and Its Nobility

An Élan for Perfection Should Exist in All Classes An Élan for Perfection Should Exist in All Classes

How Man Should Act over His Natural Environment How Man Should Act over His Natural Environment

Tradition, Stagnation and Progress Tradition, Stagnation and Progress

The Natural and Unnatural Decline of the Clan The Natural and Unnatural Decline of the Clan

The True Friends of the People Are Traditionalists The True Friends of the People Are Traditionalists

Revolution and Counter-Revolution - Overview Revolution and Counter-Revolution - Overview

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Organic Society | Social-Political | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|