|

Theology of History

Revolution & Counter-Revolution

in the Tendencies, Ideas & Facts

Atila Sinke Guimarães

I am pleasantly surprised at the good response the theme Revolution and Counter-Revolution (click here) is having among supporters of Tradition in Action. Some have asked me to go into further detail, giving a more profound explanation of the topics I touched in passing during that overview. Let me respond at least in part to this request.

I think it is important to acquaint my listener with the notions of Revolution and Counter-Revolution in the tendencies, ideas, and facts.

When did the Revolution begin? What is the transition point between the pre-revolutionary period and the revolutionary era?

To answer these questions, I will borrow some historical perspectives from Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, my mentor in the R-CR fight and in the explanation of this phenomenon.

Let me begin by noting that from a certain point of view, the history of Europe had two periods, one combative and another triumphant.

The combative period

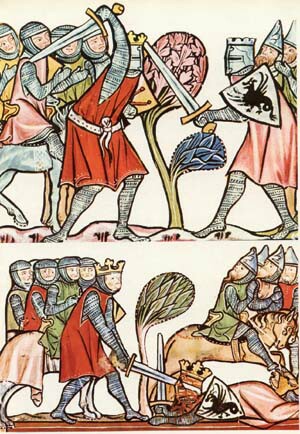

Charlemagne, in red, fighting a Muslim King |

First I will analyze the combative period. During this time there was a mixture of Latin and German peoples in Europe who were baptized and Christianized. They lived in extremely difficult conditions, their existence threatened by many enemies.

If one studies the Europe of Charlemagne (742-814) or immediately afterward, the Europe of the 9th century, the following picture emerges:

- The Arabs dominated Spain and constituted a continual danger along the Pyrenees. They made constant invasions into southern France and Italy and conquered almost all the Mediterranean coast.

- The Catholic Empire was also threatened by the Saxons from the Northeast, and by the Normans from the North, who crossed France by river, reached the Mediterranean Sea, and headed toward Sicily. From there, they set out for the Eastern Empire and burned part of Constantinople.

Today, one might think that Charlemagne reigned in a relatively peaceful time. This is not true. His reign was marked by unrest and many trials.

The triumphant period

This era of trials lasted in Europe until the 13th century, which saw a triumphant period. What happened? The Arabs were still on the Iberian Peninsula, but their supremacy was declining. They had lost considerable parts of Spain and Portugal, and the conquest of Granada with the expulsion of the last Moors from the peninsula was already in the air. Because of the waning strength of the Arabs, the Turks would expel them in the 15th century and conquer the Mediterranean coast with relative ease.

At the same time, the Saxons were completely converted to Catholicism, as were the Hungarians, who had been a great menace. The aggressive Prussians and Latvians were ready to abandon their pagan religion and customs. The Normans had integrated with other peoples, entered England, and no longer constituted a danger.

The general impression all this gives is of a Europe that had acquired a great self-confidence and conquered the dangers that threatened it. This impression generated a change in the mentality. Before, there was a combative and vigilant state of spirit. From then on, the spirit was triumphant.

Prince Henry the Navigator in his Nautical School of Sagres, Portugal, which played an important role in discovering the New World - by Adriano de Sousa Lopes |

So what emerged was the imperial and victorious atmosphere of the late Middle Ages. Instead of representing Our Lord as a suffering and crucified Martyr in the cathedrals, art and liturgy, it became popular to present Him as a King in glory, whose dominion would last to the end times. There was a clear sense that the power of Jesus Christ had been established on earth forever. The most civilized and glorious continent of the world was Catholic, and the Kingdom of Christ had been established on earth.

The medieval man had a strong sense of his vigor and all that would come from it. We should not forget that after the fall of Granada, the Iberian Peninsula launched its epic series of navigations that would result in the discovery of the Americas and European dominion over considerable parts of the East. This period would represent a prodigious expansion of Europe. And the medieval man sensed it. There was an atmosphere of great hope, expectation, and joy.

In parallel to this triumph, wars became less frequent and the customs started to change. A spirit of sweetness and softness entered the picture, and Catholics started to relax their way of being. It was a natural letdown that appeared to be a legitimate relief.

Then, the medieval man began to allow more time for pleasures. The developing social life demanded more parties and luxuries, increasingly brilliant and lavish. The songs became more lighthearted and jovial, and were no longer dominated by themes of war or religion. The arts became lighthearted and playful. Even the gothic architecture became less severe and started to frolic; it set aside its grave, stable demeanor and began to dance. It was the birth of the flamboyant gothic. This general softness of spirit continued into the 13th and 14th centuries.

This change of mentality, which in many regards was legitimate, presented the opportunity, however, for the Revolution to begin to subvert the main Catholic principle that sustained medieval Christendom. That is, the love of the cross and the correlated sense of sacrifice and spirit of fight against the enemies of Our Lord.

During the period of wars and serious adversities, love of the Cross for the medieval man was a natural consequence of being Catholic and having to face danger. Love of the cross and sense of sacrifice was second nature for the knight turned toward the expulsion of the Moors from the Iberian Peninsula, for example, or the crusader in the Holy Land defending it from the enemy. His life was dedicated to an ideal, and at every moment he risked death and standing before the judgment seat of God. Because of this love, the knight wore a cross on his chest and called himself a crusader – which means a man marked by the cross.

It was in this period of triumph that the legitimate request for relaxation and the enjoyment of innocent pleasures opened the door to the Revolution.

Introducing sensuality into the mentality of the medieval man

How did the Revolution take advantage of this legitimate relaxation to introduce sensuality into the mentality of the medieval man?

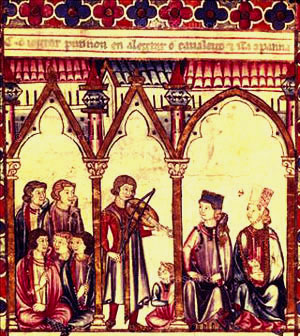

Above, a troubadour performs at the temperate court of a medieval royal couple. The ambience became extravagant in the Renaissance court. Below, a jester-dwarf with a monkey is part of a large ensemble of entertainers.

|

Through agents strategically placed, the Revolution started to exaggerate man’s appetite for earthly pleasures. In the court of the nobles, the voices of style began to dictate that the banquets become more elaborate – not only the food, but also the music. Then there were dancers performing acrobatics, buffoons telling jokes and mocking the guests with their banter. These feasts, which used to be rare, now became increasingly frequent.

The bourgeois and plebeians in the village and the peasants in the countryside would imitate the court fashions. The constant parties, tournaments, and festivals created an atmosphere of enjoying life that replaced the former serious ambience. With this, the appetite for pleasure was transformed into an unbalanced eagerness to enjoy life. So the feasts that at first were just a pleasant convenience became indispensable. With this, an important line was crossed.

This fashionable life of constant festivity was reflected in the clothing, manners, language, literature, and art. The constant quest for delightful experiences and indulgence of the senses necessarily produced softness and sensuality.

At the same time, chivalry in great part abandoned its fight for religious ideals, putting aside the defense of the Holy Land and the protection of widows and orphans. Instead, it became sentimental. It became a chivalry of love, with knights dedicated to fighting for the affections of a lady.

It is easy to realize that those pleasures were not always legitimate. The old minstrels, who used to occasionally sing the chansons de geste to bolster Catholic militancy, were replaced by an organized network of troubadours, who traveled broadly throughout Europe. Spreading courtly love in their lyrics, they frequented the castles of kings and nobles, or entertained the people at the markets and fairs.

Often, the themes of these songs were no longer moral and decent. For instance, it was popular for a time for them to sing songs describing in great detail the nude body of Eleanor of Aquitaine, the heiress of one of the most powerful dukedoms of France. She married Henry Plantagenet, the King of England, and became the mother of Richard the Lionhearted and John the Landless. Her court in Aquitaine, and afterward in England, was one of the focal points to spread the courteous love that came to dominate chivalry and the noble courts. It was also a center for the organized company of immoral troubadours whom she welcomed and patronized.

The great halls became extremely rich and expensive

Fugger-Castle in Kirchheim, Germany |

Just in passing, let me observe that when this fever for pleasures became dominant, another correlated imbalance occurred. Financial needs increased considerably to keep up with the novelties – new décors for the dining rooms and halls, expensive parties, fashionable dresses, stipends for the musicians and artists, etc.

Consequently, many of the stable financial sources of the past that were primarily linked to the land could no longer cover the many extra expenses. With this, the need for new businesses with rapid gains appeared. But, as often happens, many of the businesses were not successful. To respond to this new financial need, men appeared in strategic places of society who were prepared to lend money to the nobles or bourgeois in need of funds.

Therefore, without introducing any explicit doctrine, the Revolution was able to change the mentality of the medieval man, transforming the love of the cross he had into a spirit of enjoyment of life. This triggered an artificial process of sensuality that was manipulated and controlled by the Revolution.

Pride and vanity begin to dominate the medieval man

How did the Revolution manipulate pride in the medieval man?

Parallel to this sentimentalism, a favorable atmosphere was created for the medieval knight to abandon his old modesty and begin to boast about his war adventures. He was encouraged to taste the pleasures of vanity by receiving eulogies describing his prowess. Then, to win even more applause from an audience eager for such reports, the knight would exaggerate his achievements.

The Renaissance knight became a man of show

and a braggart |

It did not take long for him to become a braggart. He would boast, for example, that in such-and-such a battle with his single lance he killed five Moors in a row, one after another, like a man putting sausages on a stick. Another time, he struck at an Arab and missed, but his blow was so strong that when his sword hit an enormous rock in the mountain, it split the rock top to bottom into two pieces.

Often such phony heroes would compete among themselves to invent stories of their prowess to win the easy applause of the fashionable and superficial court audiences. Soon this ambience of competition fed by pride and vanity became established in the noble courts, and even inside chivalry itself. This spirit of pride and unabashed conceit was quite different from the former reserve and disinterest of the medieval knight, whose only goals were to destroy the enemy of Christ and acquire merits for Heaven. It was in reaction to these ostentatious displays of pride that Cervantes would write his famous Don Quijote de la Mancha.

Further, some well placed persons influenced court ambiences so that in addition to these lively descriptions of battle prowess, the knight also felt the need to show that he had read this or that poet, he knew how to sing such-and-such song; he was familiar with that new style of dancing.

In this marketplace of vanities, it also became the fashion for the noble to know something about classical Latin or Greek authors and drop several of their lines in conversation. When the door of this court life opened to some educated and worldly ecclesiastics, as well as learned and intelligent lay professors and talented artists, they brought more erudition and brilliance to the ensemble. But they also created a new point of comparison that obliged the nobles to learn a better Latin and a bit of Greek, and to study art and philosophy so that they could keep up in the social circles and not be considered rustic.

This was the means the Revolution used to change the humble and serene medieval man turned toward the glory of God into a proud and superficial peacock absorbed in himself and his own exploits and talents, spending a considerable amount of his time catching up with the latest fashions. This is how the medieval man became the Renaissance man.

Neither doctrine nor ideas were spread to achieve this goal. Just a genial work methodically directed to stimulate two main human passions – pride and sensuality – in order to implant a new mentality. Once the mentality had changed, the spirit was prepared to receive the new ideas.

This was the efficiency of the first Revolution in the tendencies.

Revolution in the Ideas

The principal new current of thinking of the times came from the Colleges of Law, principally those at the Universities of Paris and Bologna, which gave birth to the legist. The legists were scholars of Roman Law, probably linked among themselves in various secret societies, who affirmed that Roman Law should organize all the States at any time in History.

The pride and the theatrical air of the Renaissance man is apparent in this detail of a painting by Sandro Botticelli |

According to this doctrine, whatever an individual prince dictates should acquire the strength of law in the State, just as it was in the Roman Empire. That is to say, the legists preached Absolutism: the absolute will of the king should prevail. As a consequence, the legists were against the Catholic and organic medieval way of ordering the State.

The State in the Middles Ages was made up of social bodies that were politically autonomous in everything that concerned their own interests. They accepted the authority of the king only in matters of common interest. The king could not intervene in those organic bodies except on very extraordinary occasions. These institutions relied on an ensemble of private laws (privilegia, or privileges) granted to them through a long period of time that protected them from ordinary royal intrusion.

The legists, on the contrary, desired a political order where the king would have an all-powerful authority. For this reason, the legists combated the influence of the Church that so wisely established limits on royal authority. They also tried to diminish the power of the nobility and the other intermediary social bodies, such as the innumerable professional guilds, the universities and student associations, the hospitals and orphanages, the parish corporations of faithful people, the private police forces, and the associations of art and culture. These autonomous organizations with their own laws and privileges were obstacles for the application of the supreme royal power the legists wanted to establish.

The legists found a ready audience for their doctrine among the kings. Along with the average medieval man, the king had also been prepared by the Revolution in the tendencies. He wanted to enjoy life, shine in the court circles, and be the unique center of attention and admiration. Therefore, when a legist would come to him and say, “Your Majesty has the right to command everyone,” these words were music to his ears. He would think: “This legist is right. I will support him.” It is easy to understand how one thing leads to another; how bad tendencies prepare one to accept an erroneous idea.

With the appearance of the legists, the centuries-old question of royal investiture – which had been virtually resolved by Pope St. Gregory VII in the 11th century when he prevailed over Henry IV – returned to the scene with new strength.

Absolutism was worse than the Investiture Question

Let me make a brief resume of the investiture question. From the fourth century, Emperors and Kings were falsely assuming the right to name Bishops and even Popes, convene councils, and intrude into ecclesiastical affairs. After Constantine promulgated the Edict of Milan, which freed the Church from the catacombs, he thought that he would have an ascendancy over the Catholic Church, just as the Emperor had in the pagan idolatry. The Roman Emperor was considered the Pontifex Maximus [Sovereign Pontiff] of the pagan idolatry. The Church engaged in a long fight against this abusive intrusion of the royal power, affirming her autonomy before the State and struggling for her complete sovereignty.

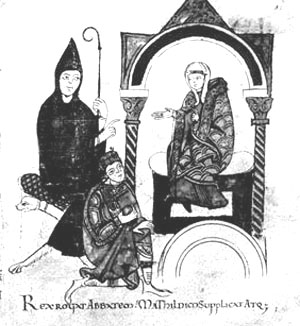

Emperor Henry IV on his knees before Mathilda imploring her to intercede on his behalf to Pope Gregory VII. Abbot Hugh of Cluny is pictured at left |

After centuries of ups and downs, this dispute came to a climax in the 11th century when the Emperor of the Holy Roman German Empire, Henry IV, arrogantly tried to impose his will over the Church in Germany against the express orders of Pope St. Gregory VII. The Emperor not only nominated the Bishops, but convened a council and obliged it to depose the Pope. Replying to this rebellion, St. Gregory VII excommunicated Henry IV and deposed him from the imperial throne. It was the first time in History that a Pope deposed an Emperor.

The German nobles, subjects of Henry IV, threatened to elect another Emperor if he did not receive pardon from the Pope within a year's time. So Henry IV, barefoot and wearing a hair shirt, went to ask pardon of the Pontiff. The Pope was at Canossa in northern Italy in the castle of one of his friends, Countess Mathilda of Tuscany. After three days of waiting in the snow outside the castle, Henry IV was forgiven by the Pope, on January 28, 1077, only four days before the deadline set by the German nobles.

It should be noted that St. Gregory VII wanted to let the deadline expire and see Henry IV deposed. Actually, he had stopped in Canossa on his way to Augsburg where, at the request of the German nobles, he was to preside over their assembly to elect the new Emperor. But he was pressured to forgive Henry IV by his traveling companion, Abbot Hugh of Cluny, one of the most powerful men in the Church. Countess Mathilda also favored the pardon.

But this forced pardon did not deprive the episode of its symbolism: the Emperor of the Holy Roman German Empire, the most powerful man in the world, barefoot in the snow, wearing a hair shirt and humbly asking forgiveness from the Pope. Even though the final solution for the investiture question would come 47 years later (in 1124 under Pope Calixtus II), the episode at Canossa is the symbol of the supremacy of the Pope over the Emperor and the virtual victory of the Church in the question of royal investiture.

The victory of the Church in the 11th century constituted one of the most important landmarks in the establishment of the Kingdom of Christ on earth. For that reason, one of the first attacks the Revolution made against Christendom was to induce kings to deny the supremacy of the Church. The legist movement did exactly this. It prepared a false doctrine for the kings to justify exerting their command over the Church.

St. Peter teaches us that the sinner who repents and returns to his sin is like the dog that returns to its own vomit, and Our Lord tells us that the soul of this kind of sinner is possessed by devils seven times worse than those present at his first sin. This applies to the Absolutism of the late Middle Ages: it was seven times worse than the old question of royal investitures.

The effects of Absolutism

The doctrine of Absolutism would predispose kings against the Church and prepare for their adhesion to Protestantism in Germany and the Baltic Kingdoms, and to Anglicanism in England. In France, Gallicanism was also intent on diminishing papal authority and increasing the power of the State over the Church. It almost became an analogous heresy. But France did not become Protestant. She remained Catholic, but professing a Catholicism influenced by those bad ideas, which would generate many bad consequences in History, the last being Liberalism, the father of Modernism.

Absolutism would also have profoundly harmful effects on those healthy medieval intermediary bodies. It would stimulate the destruction of their laws, privileges, and symbols. One can see later examples of this destruction that came from the legist doctrine in the French reforms of Richelieu and Colbert, respectively ministers of Louis XIII and Louis XIV. They aimed at destroying the patrimonies and castles of the medieval nobles. It was not just the great families who lost their medieval characteristics; a large part of the medieval regional system of laws and taxes that kept the country decentralized was also dissolved.

The French Revolution also strove to demolish any remaining feudal laws and privileges as well as symbols. It is worth noting that the revolutionaries killed the King, Queen, and nobles for being representatives of the medieval order, not because they were absolutists. In fact, Absolutism lent a hand to the French Revolution by spreading the foundation for the Enlightenment. Frederick II of Prussia, Joseph II of Austria, and Catherine the Great of Russia who helped Voltaire and the philosophers spread the Encyclopedia during the Ancien Regime. They were absolutist Monarchs. When the phase of the Terror ended in the French Revolution, Absolutism returned to power with Napoleon to spread the nefarious principals of that Revolution throughout the world.

However, the Absolutism promoted by the legists was not the only system of ideas used to spread the Revolution in the late Middle Ages.

It was popular to decorate walls with immoral pagan scenes. Above, the fresco Bacchanalia in an Italian Palace of Mantua - Giulio Romano |

From the beginning of the 14th century, under the pretext of Humanism and Renaissance, a return to Paganism was promoted by the secret forces. Toward that end, Roman and Greek customs, language, literature, and art became the fashion. The old Roman and Greek mythologies became popular and were played on stage almost everywhere. Spreading the stories of pagan mythologies, the arts exalted nudism, adultery, free love, incest, homosexuality, and even bestiality with the much disseminated tale of Leda, for example, who had love relations with a swan from which a daughter was born, Helen of Troy. This is how the arts promoted sensuality.

Regarding pride, Humanism and Renaissance encouraged the arrogant “new man” to despise and reject the former Catholic ideas and the whole medieval civilization as barbarian and “obscurantist.” That is, the Catholic man became so full of himself that he despised and rejected the Catholic Civilization the Church had built. Instead, he admired and adopted the same Paganism that the Church had annihilated many centuries before.

In parallel, the secret forces encouraged Nationalism among the peoples of each country. “We the French are more than the Spanish;” “We the English are better than the French;” “We the Germans are greater than the Italians,” and so on. The same pride that generated individuals to boast and appear the most learned and refined now expanded to a competition between countries and peoples. It was the birth of Nationalism and the fading of the ideal of Christendom.

In short, the main ideas spread by the Revolution were:

- Absolutism, expressed in the advice of the legists to the kings.

- The Renaissance in the arts.

Such ideas opened the door in turn to new tendencies. Nationalism, for example, first appeared as a tendency. Later it would become an articulated system of ideas.

Revolution in the facts

In many places revolutionary tendencies and ideas took a long time to reach their complete development. In others, however, as in France, the dynamism of the vices they unleashed was so powerful that the medieval order changed in just a short period of time, producing the actual events that established the beginning of the Revolution.

In many senses, the Middle Ages was at its apex when St. Louis IX of France was reigning. At the same time, St. Ferdinand ruled over Castile, and other saints were or had been at the head of the Holy Roman German Empire and the English and Hungarian kingdoms. The influence of the Church was enormous. She had never before enjoyed the material means she had at that time. The laws of the States were turned to favor virtue and repress vice. Everything appeared to be perfect.

Notwithstanding, a short time after the death of St. Louis in 1270, the Revolution would start. Actually, in 1303, his grandson Philip IV, King of France, would order the criminal assault against Pope Boniface VIII, which marks the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the Revolution. It was the symbolic assault of Anagni. Let me describe what happened.

King Philip IV is also known as Philippe le Bel, or Philip the Fair in English. He was an absolutist and a despotic King deeply influenced by the legists, namely, Pierre Flote and Guillaume Nogaret, who were his personal advisors. The trio – Philip IV, Flote, and Nogaret – were committed to destroy the Pope’s supremacy over the Kings of Christendom.

The criminal assault of Anagni marks the beginning of the Revolution.

Above, Pope Boniface VIII |

The facts developed in the following manner: Philip IV had obliged the French clergy to pay heavy taxes to the crown in order to help him pay his bills for a war with England. Then, he took a further step. He arrested Bishop Bernard Saisset, who had been named Bishop of Pamiers by Pope Boniface VIII without the previous agreement of the King. Saisset was charged with grave crimes invented by the trio, who did not hesitate to slander the Bishop to achieve their goals. No evidence whatsoever was presented regarding the alleged crimes, and Bishop Saisset had recourse to the Pope against such an injustice.

Pope Boniface VIII intervened, asking the King to free the Prelate. He sent Philip the Bull Ausculta fili [Listen to me, my son], in which he stated the doctrine of St. Gregory VII about the superiority of the Pope over temporal monarchs. The bull was burned by the advisors of the King in his presence, and the King and his legist counselors prevented it from being circulated in France. Instead, Flote and Nogaret wrote a false bull, which was broadly disseminated and was aimed at stimulating French nationalism and setting the people against the Pope. This fake bull was intended to fuel the slanders already being spread by the trio that Pope Boniface VIII was a heretic, simoniac, and an invalidly elected Pope. The King called a meeting of the Estates General in Paris and Pierre Flote delivered a skillful speech against the Pope, painting him as an enemy of the Kingdom.

Simultaneously, Boniface VIII convened a synod in Rome to define the relations between the spiritual and temporal powers. It was on that occasion that he issued his famous bull Unam Sanctam.

In the meantime, Philip IV sent Nogaret to Italy to kidnap Boniface VIII and bring him to France to be judged and deposed by a council of Bishops controlled by the King. With this intent, Nogaret showed up at Anagni, where the Pope was passing the summer in the castle of his family. The French legist headed a mob of 2,000 men, some of them Italians under the leadership of Sciarra Colonna. After the mob had looted the castle’s treasure it arrived at the chamber of the Pope.

Guessing the plot, Boniface VIII attended them solemnly seated on his pontifical throne, wearing the tiara and carrying the keys of St. Peter in one hand and the cross in another. To the insults of the soldiers, the 80-year-old man replied not a word. To Sciarra Colonna, who threatened to kill him, he said: “Here is my neck; here is my head.” A solid tradition remains that Colonna slapped the Pope across the face on that fateful September 7, 1303.

When Nogaret pressured him to abdicate, he replied: “I will die as Pope.” Nogaret then hypocritically declared to the Pope that he arrested him “in accordance with the regulations of Public Law and for the defense of the Faith.” This moral torture lasted for two days, until September 9, when the people of Anagni raised up in favor of Boniface VIII. Shouting, “Long live the Pope,” they expelled Nogaret and his men from the city. Accompanied by 400 horsemen who had come from Rome, he retuned to the Holy City, but those terrible sufferings caused his death one month later.

Philip IV did not back off in his intent to control the Papacy, and two years later, he managed to elect a French Cardinal as Pope, who took the name of Clement V. He was escorted to France by French troops, remained captive there, and was obliged to obey the Monarch in all matters of importance. This was the beginning of the 70-year Avignon Captivity. It also broke the supremacy of the Papacy over the temporal monarchs as it was characterized in the Middle Ages.

Philip IV lost his three sons and remained without male descendants. The dynasty ended with him. His only daughter, Isabelle, would marry the future Edward III, King of England. It was in fighting for her supposed rights to the crown of France that a war began between England and France – the One Hundred Years War. This ensemble of facts constituted the chastisement of God for the sin of Philip IV and the start of the Revolution.

The criminal assault on the Pope at Anagni marks the beginning of the Revolution. The preparation was made by a careful work in the tendencies that released the dynamics of pride and sensuality. Those tendencies were confirmed by the spreading of bad ideas - Absolutism, Humanism, and the Renaissance – that started a whole revolutionary process which would destroy all of Christendom. Everything was contained in that symbolic fact.

What could have prevented the Revolution?

What should have been done to prevent the Revolution in the Middle Ages? How should the Counter-Revolution act in the Reign of Mary to avoid a similar conspiracy?

Let me set out only two fundamental principles of the Counter-Revolution.

The Middle Ages witnessed a psychological situation that is very important for us to consider, since it could occur again in the Reign of Mary after the triumph over the enemies of the Catholic Church.

1. The need of a special type of vigilance

In the Middle Ages, something very profound was missing in the Catholics who had, nonetheless, an intense faith and a great sense of sacrifice. They accepted the cross and carried it with panache, but they were not convinced that the cross should be carried even if the circumstances were not difficult and hard. They were not convinced that the spirit of militancy should continue even if there were no longer Moors and pagans to combat. They should have been convinced that life for a Catholic is irremediably hard and filled with sufferings in its very essence. These sufferings are a consequence of man being conceived in original sin. The Catholic life is on a wrong path when it is not difficult.

Once the difficulties had eased, the medieval Catholics should have had a great concern to not lose the love for the cross and the sense of sacrifice. They should have foreseen that it would be more difficult to be faithful to grace during a victorious era than when they were surrounded by enemies and trials. This was a matter to be dealt with by the spiritual authorities of society. Sermons from the pulpits, advice in the confessionals, and perhaps a special religious order to maintain vigilance should have preached this truth: the worst danger comes with victory. The victory is the hour when most men lose their values. After winning the wars, it was imperative to know how to win the victory.

Instead, an attitude of relaxation and lack of vigilance caused the decline of the Catholic spirit, and an explosion of pride and sensuality moved society toward the goals of the Revolution.

Therefore, to be worthy of being a part of the Reign of Mary, we should be extraordinarily careful - with ourselves and others – to keep alive a true love of the cross and the correlated spirit of fight and sacrifice. Without these elements, the new society of the Reign of Mary will again become prey to the same revolutionary process.

To have vigilance regarding these points is, therefore, absolutely essential. However, there is something still more important.

2. The need for a special type of militancy

The decline started when the Catholics stopped being intransigent and aggressive toward evil. Only an energetic and violent reaction is capable of stopping the progress of evil. The real problem is not that the bad people are audacious, but that the good people are less intolerant of evil than the evil people are of good.

The evil ideal begins to win when good Catholics lose this kind of intransigent militancy. From the Middle Ages to our days, the attitude of the apostles of the Church has been defensive. On the whole, the soldiers of the Church have always been turned toward building defensive walls. There have been a few men with the intransigent militancy who took the offensive and raised heroic resistances against the Revolution.

This was the case of St. Ignatius of Loyola whose spirit of fire and untamed militancy generated the Council of Trent and the movement of the Counter-Reformation and would have completely defeated Protestantism and built a new Catholic world if the Revolution had not infiltrated his work, the Society of Jesus. This was the case of St. Louis Grignion de Montfort, whose apostolate gave birth to the Counter-Revolutionary movement of the Vendée and Bretagne against the French Revolution.

The reason this intolerant militancy is necessary is related to the dynamism of the passions. What happens in society at large simply replicates what happens in the souls of individuals. The unleashed passions have an extremely powerful dynamism that expand in and dominate the person. The complete development of a passion is already contained in its first manifestations.

Only an intransigent and agressive reaction is capable of stopping the progress of evil - Battle of Poitiers |

For a man who has pride as his capital vice, even if he fought all his life against this vice, when he makes a small concession – listening with complacency to flattery, for example – this small concession carries within itself the potential for further concessions and the more delirious excesses, the desire to be adored, for instance. He may not reach that extreme immediately, but the process leading to it was unleashed. The way the passion expands and accelerates does not follow a predictable, steady formula. Rather it can expand to 1 at the first concession, 10 at the second, 1,000 at the third, and then reach 1,000,000 at the next. It is similar to a chain reaction explosion, like an atomic explosion.

Of course, this kind of rapid expansion does not occur with every vice in every person. It takes place with the primordial vice of a man. The primordial vice, or main vice, is the one that characterizes the easiest way each man is tempted by the Devil to oppose the plan of God for him. It is his weak spiritual point – his Achilles heel. The good moralists advise the Catholic man to oppose virulently the first manifestations of his capital vice, never to be tolerant with it or open the door for any concession to it. The opposite of the capital vice is the primordial light, which means the principal virtue a person is called to practice in order to be a worthy image and likeness of God.

The vices of men follow the seven capital sins, just as the virtues follow the seven virtues. The moralists explain that the seven vices can be assembled into two groups:

- pride – which also includes envy and anger;

- and sensuality – which is synonymous with lasciviousness, and also includes gluttony and laziness.

The buckle that links these two currents of vices is avarice. It is a vice that relies on pride with regard to exerting power over one’s neighbor, and on sensuality as far as it generates a lust for money similar to the lust in the sins of the flesh.

Therefore, a Catholic needs to analyze himself to know his capital vice and oppose it relentlessly and avoid falling into it; otherwise he will become an easy prey for the Devil.

In a similar way, the whole social body must have an intolerant militancy against the slightest manifestation of the revolutionary vices. What are these vices? In society, pride and sensuality are the main vices. Pride is the revolt against the order of society, the reflection of the order of God’s creation. It also entails revolt against the legitimate hierarchy in society. Sensuality in the social sphere is the eagerness to be free of any restraints or coercion, to not follow the rules – be they moral norms, social guidelines, or political laws.

As I noted earlier, the Middle Ages unfortunately did not have a militancy that was intolerant enough against these vices. Instead, there was a first tolerance toward sensuality that brought all the other concessions in its wake. All the sensual abuses of the Renaissance were contained in that first concession. Analogously, all the revolt of Luther was already contained in the absolutist pride of the kings and their arrogance toward the Popes.

To avoid falling into the revolutionary process, the Middle Ages should have had an intolerant and aggressive militant reaction against these first manifestations of sensuality and pride. This would have cut the whole process in its germ state.

Instead, Catholics adopted the revolutionary sophism that preaches it is always necessary to show a certain tolerance toward evil and make some concessions to the enemy in order to keep peace.

From this came the establishment of the Revolution inside Christendom, the gradual destruction of that social body, and the infiltration of the Revolution inside the Catholic Church herself so that the Revolution might triumph over the world. This is what we have today.

To avoid a similar process being reborn after the victory of Our Lady and the establishment of the Reign of Mary, we must maintain a keen vigilance in victory so that we do not lose that love for the cross and the spirit of suffering and fight, as well as sustain an intransigent, dynamic, and invincible militancy toward evil.

Posted November 14th, 2005

Related Topics of Interest

Revolution and Counter-Revolution Revolution and Counter-Revolution

Defending the Crusades Defending the Crusades

The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth The Swan's Song of Galileo's Myth

The Personality of Charlemagne The Personality of Charlemagne

Related Works of Interest

|

|

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us |

Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|