Manners, Customs, Clothing

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Catholic Approach to Hiking - 1

‘So Nature Excites Them in Their Hearts’

A medieval couple walking along woodland paths

This call, this natural impulse in the soul of man, is a desire to view and know the wonders of Creation. One way a man fulfills this desire is by walking outdoors, today commonly referred to as hiking.

Hiking is a marvelous way to glorify God in His creation, if done in the correct spirit. To the modern ear, hiking can sound like an activity for outdoor adventurers, hippy-types or athletes. However, this was not the spirit of the past. Our Catholic forebears knew much more about hiking than the typical nature enthusiast of today.

The medieval man & the natural world

The natural world was very familiar to the medieval man, for his lifestyle and customs artlessly maintained the natural environment and his own well-being.

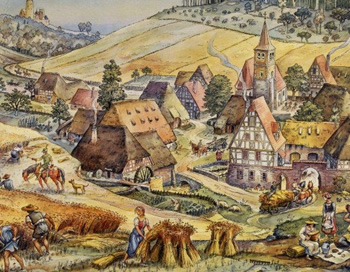

The medieval village with its close connection to the countryside

Although hiking and camping as typically pursued today did not exist until the 18th century, in the days of Christendom such activities were naturally incorporated into life. In the Middle Ages, peasants would not often venture too far from the villages of their childhood, but these villages were surrounded by charming countryside, hills and forests. As a part of his everyday life and work, the peasant entered those landscapes.

Harvest picnic by Adrian Ludwig Richter

In the countryside he also took his leisure, strolling peacefully on roads and hidden paths that led through the lands around his village. During harvest season, peasants often ate their midday meals in the fields, and a good harvest could mean festive picnics in the grand outdoors.

Sundays and feast days, days of merriment and relaxation, were passed in countryside walks or religious processions that could cover a distance of many miles. Indeed, just the morning walk to the church, which could take several hours, was a natural form of engaging in what today would be called "exercise."

Yet, it was not only the peasants who enjoyed nature. The nobles, kings, and queens were also much closer to the natural world than we are today. Most of the old medieval palaces were surrounded by forests or plains or set on mountaintops.

Candlemas Day walking to church

Further, medieval cities were not so far removed from the country as they are today. For instance, one of the largest cities in the Middle Ages was Paris, which was enclosed by a wall that expanded in the 14th century to include approximately 1,000 acres of land and an estimated population of 200,000. (1) A city dweller could easily leave the city gates to spend a day in the country.

The people in the Middle Ages generally traveled by foot. They walked to church, to visit neighbors or to town. The upper classes could travel by horse or carriage, but some chose to walk as a form of humility and penance or to visit the poor and sick of their kingdoms, as St. Elizabeth of Hungary and St. Margaret of Scotland were wont to do. For the most part, when people from the upper classes walked, it was a form of recreation and not of necessity.

Whether out of necessity or for recreation, the medieval man was constantly walking. Thus he felt neither need nor desire to travel far away to visit a nature reserve or explore a hiking trail, as we must do today in order to escape the modern megacities and miles of sterile neighborhoods.

Walking with a purpose

Indeed, the mindset of the medieval man was different from that of the modern man; he did not travel in order to go hiking or camping. He traveled to go on a pilgrimage, to do his errands and carry out his daily work, to visit another village or city, in short, to reach a determined destination. If there were no hostel or inn along the way, he had to be prepared to camp and sleep in the woods or along the roadside.

Walking with an aim in view

There were even some adventurous spirits who made long expeditions across countries and into deep unknown lands. The most famous explorer of the medieval period was Marco Polo, who wrote a book about his experiences in the East. Another acclaimed early Renaissance adventurer was Francesco Petrarca, better known as Petrarch, who achieved his goal to climb a mountain, Mont Ventoux, with his brother in 1336.

For the average person, hiking long distances was undertaken as a necessity or as a part of a pilgrimage. These pilgrimages were often ventured with the aim to fulfill a promise or penance, or perhaps to receive a special blessing or indulgence. But they also opened a new world to the pilgrim, with marvelous sights and wonders to behold, inspiring him to give greater glory to God as he marveled at His Creation.

This desire to travel to see far-away lands is captured in Chaucer’s poem titled The Canterbury Tales.

In its Prologue he describes how, when spring arrives with all its renewing showers and warmth, it awakens the desire in man to venture out into the world from which he was so long barred and to give thanks to God and the Saints for surviving the hardships of another winter:

On pilgrimage

Has pierced the drought of March to the root,

And bathed every vein (of the plants) in such liquid

By the power of which the flower is create ...

And small fowls make melody,

Those that sleep all the night with open eyes

(So Nature incites them in their hearts),

Then folk long to go on pilgrimages,

And palmerers long to seek foreign shores,

To go to distant shrines, known in sundry lands.

And professional pilgrims (long) to seek foreign shores,

And specially from every shire's end,

Of England to Canterbury they travel,

To seek the holy blessed martyr,

Who helped them when they were sick. (2)

As can be seen from this poem, pilgrimages were a cherished part of the medieval world, yet it was not only devotion to the saint or shrine to which they traveled, but also because nature was urging them to travel through the world to see some of her beauties. It was a natural consequence of the medieval man’s communion with God, Who is better known and loved through His Creation.

Yet, alas, too soon a new era would come with the iron horses of ‘Progress’ marching in and trampling over the world, corrupting the innocence and simplicity of a more pure life. This, however, is the topic for the next article.

A leisurely stroll

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_in_the_Middle_Ages

- See Old English verse

here:

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour....

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(So priketh hem Nature in hir corages),

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

- https://recipereminiscing.wordpress.com/2015/03/13/the-history-of-picnics/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hiking

- https://www.medievalists.net/2019/08/travel-middle-ages-road/

- Ohler, Norbert. The Medieval Traveller. Woodbridge, The Boydell Press, 2010.

Posted October 6, 2021

______________________

______________________