Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personification of Principles - I

The Phenomenon of Imitation in Society

In the Middle Ages, all men recognized a general principle regarding imitation that is profoundly different from the opinions of the liberal society in which we live today.

According to our liberal society, the norm for a man is to be completely free: after reaching majority at age 21, he has all the rights to choose what he wants, obeys no one but the State, and expects no one to obey him.

I showed in another series of articles that, in the political and social order, the medieval man was the opposite of this: He was bound by contracts to other men to whom he would fully obligate himself either as a superior or an inferior. With these men he formed contracts of solidarity, which found its more typical expression in feudal allegiance.

I showed in another series of articles that, in the political and social order, the medieval man was the opposite of this: He was bound by contracts to other men to whom he would fully obligate himself either as a superior or an inferior. With these men he formed contracts of solidarity, which found its more typical expression in feudal allegiance.

This pledge of himself was life-long and constituted not only a commitment of services, but a lifetime inter-relationship, an inter-participation of all interests and ideals. This alliance generated the obligation of protection on the part of the superior, which was the duty of the suzerain, and the obligation of fidelity and obedience on the part of the vassal.

The ideal of the medieval man, therefore, was never to be completely free and independent, to do whatever he wanted and have neither anyone above him nor below him.

The difference of the mentality in our days has generated a very interesting consequence with regard to imitation.

For the contemporary man, imitation is presented as something shameful. Today, almost no one will say that he imitates someone else or that he learned something from another person. He would never say, for example, “Since I don’t know how to do this, I will go see how Mr. X does it, and then I will do it the same way.” It is a rule of our liberal society to never openly admit such dependence; it is contrary to the republican spirit of equality of all men.

If all men are equal, no man should imitate another, no one should go to another to learn lessons and receive orientation. Imitation is viewed as shameful in the eyes of the modern man.

If all men are equal, no man should imitate another, no one should go to another to learn lessons and receive orientation. Imitation is viewed as shameful in the eyes of the modern man.

Some time ago, a person told me that he had seen a youth taking the position of a disciple in relation to an older man. This attitude was described as something shameful. Today, no one should be the disciple of anyone else. Even though our liberal society is amoral – having abolished the rules of the true morality – it still has its own morals, which includes taboos like this. This is, in fact, one of its most characteristics taboos. This interdict makes it more or less impossible for us to hear someone say: “He is my master, my model, and I choose to be inspired by him to know how to act.”

Imitation is a necessary social phenomenon

At the same time that it outwardly rejects imitation, our society lives by imitation, because imitation is a necessary social phenomenon. I believe that society would cease to exist if imitation were to disappear.

In what fields can imitation be observed?

It can be verified principally in topics related to fashion. Fashion lives from imitation. People need to know what is in style at the moment, which does not obey any reasonable rule. For example: some years ago, it was the unwritten rule that a man going to a wedding should wear a navy suit and a silver tie. Today, this is no longer the fashion, and the poor man who appears with a silver tie at a wedding is viewed as hopelessly out-of-date since he has not realized that a silver tie is no longer worn for weddings.

It can be verified principally in topics related to fashion. Fashion lives from imitation. People need to know what is in style at the moment, which does not obey any reasonable rule. For example: some years ago, it was the unwritten rule that a man going to a wedding should wear a navy suit and a silver tie. Today, this is no longer the fashion, and the poor man who appears with a silver tie at a wedding is viewed as hopelessly out-of-date since he has not realized that a silver tie is no longer worn for weddings.

How did this change of fashion occur? It is because within the top society of São Paulo a certain group of persons decided to change the rule. However, the society of São Paulo followed this norm because the persons of high society in Paris, London or New York launched it. It is a rule that was launched from a higher place and had repercussions here. Needless to say, women have their attention turned toward fashion much more than men.

In passing, let me assert that this custom of imitation blatantly contradicts today’s liberal egalitarian principles. Although everyone follows the fashion, no one would dare to say, “I am watching the latest fashion trends so I can follow them:” Even a lady avoids admitting this dependence.

But, fashion in dress is not the only field of imitation. The modern man imitates movie stars to the point of changing his entire personality. Even styles of houses go in and out of fashion.

Ways of working also go in and out of style. For instance, among lawyers, a certain shrewd technique suddenly gains attention and spreads. Everyone in the profession learns and applies the trick. Then, after a while, that ploy loses its popularity and another fad appears that represents the up-to-date lawyer.

This happens in all professions and with all types of things: food, medicine, sports, to mention just a few. Today, imitation is imposed in everything, although very rarely it is admitted.

Imitation is a human phenomenon that supposes a certain type of dependence. In its turn, dependence supposes hierarchy, which is against republican equality. For this reason, this very evident phenomenon plays a more or less clandestine role in today’s society.

So, imitation has a legitimate reason for existence, but the modern man engages in it in a wrong and servile way. What is our Catholic counter-revolutionary position with regard to the role of imitation in society? What is the real reason for it? What are its legitimate limits? How should this custom of imitation become an institution in an organic society?

We will start to answer these questions in the next article.

Continued

According to our liberal society, the norm for a man is to be completely free: after reaching majority at age 21, he has all the rights to choose what he wants, obeys no one but the State, and expects no one to obey him.

The foundation of medieval society was the notion every man should serve a superior

This pledge of himself was life-long and constituted not only a commitment of services, but a lifetime inter-relationship, an inter-participation of all interests and ideals. This alliance generated the obligation of protection on the part of the superior, which was the duty of the suzerain, and the obligation of fidelity and obedience on the part of the vassal.

The ideal of the medieval man, therefore, was never to be completely free and independent, to do whatever he wanted and have neither anyone above him nor below him.

The difference of the mentality in our days has generated a very interesting consequence with regard to imitation.

For the contemporary man, imitation is presented as something shameful. Today, almost no one will say that he imitates someone else or that he learned something from another person. He would never say, for example, “Since I don’t know how to do this, I will go see how Mr. X does it, and then I will do it the same way.” It is a rule of our liberal society to never openly admit such dependence; it is contrary to the republican spirit of equality of all men.

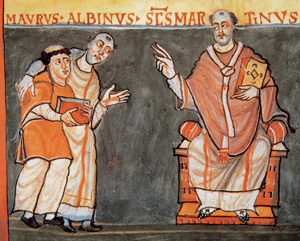

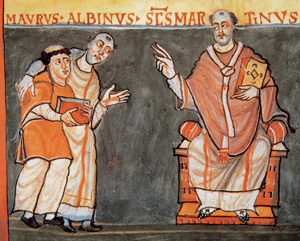

Maurus Albinus presents a disciple to St. Martin

Some time ago, a person told me that he had seen a youth taking the position of a disciple in relation to an older man. This attitude was described as something shameful. Today, no one should be the disciple of anyone else. Even though our liberal society is amoral – having abolished the rules of the true morality – it still has its own morals, which includes taboos like this. This is, in fact, one of its most characteristics taboos. This interdict makes it more or less impossible for us to hear someone say: “He is my master, my model, and I choose to be inspired by him to know how to act.”

Imitation is a necessary social phenomenon

At the same time that it outwardly rejects imitation, our society lives by imitation, because imitation is a necessary social phenomenon. I believe that society would cease to exist if imitation were to disappear.

In what fields can imitation be observed?

Count and Countess Edouard Decazes at Chantilly, France, in the '50s: Setting an elegant tone for society

How did this change of fashion occur? It is because within the top society of São Paulo a certain group of persons decided to change the rule. However, the society of São Paulo followed this norm because the persons of high society in Paris, London or New York launched it. It is a rule that was launched from a higher place and had repercussions here. Needless to say, women have their attention turned toward fashion much more than men.

In passing, let me assert that this custom of imitation blatantly contradicts today’s liberal egalitarian principles. Although everyone follows the fashion, no one would dare to say, “I am watching the latest fashion trends so I can follow them:” Even a lady avoids admitting this dependence.

But, fashion in dress is not the only field of imitation. The modern man imitates movie stars to the point of changing his entire personality. Even styles of houses go in and out of fashion.

Ways of working also go in and out of style. For instance, among lawyers, a certain shrewd technique suddenly gains attention and spreads. Everyone in the profession learns and applies the trick. Then, after a while, that ploy loses its popularity and another fad appears that represents the up-to-date lawyer.

This happens in all professions and with all types of things: food, medicine, sports, to mention just a few. Today, imitation is imposed in everything, although very rarely it is admitted.

Imitation is a human phenomenon that supposes a certain type of dependence. In its turn, dependence supposes hierarchy, which is against republican equality. For this reason, this very evident phenomenon plays a more or less clandestine role in today’s society.

So, imitation has a legitimate reason for existence, but the modern man engages in it in a wrong and servile way. What is our Catholic counter-revolutionary position with regard to the role of imitation in society? What is the real reason for it? What are its legitimate limits? How should this custom of imitation become an institution in an organic society?

We will start to answer these questions in the next article.

Continued

Posted March 10, 2014

Organic Society was a theme dear to the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. He addressed this topic on countless occasions during his life - at times in lectures for the formation of his disciples, at times in meetings with friends who gathered to study the social aspects and history of Christendom, at times just in passing.

Prof. Plinio

Atila S. Guimarães selected excerpts of these lectures and conversations from the transcripts of tapes and his own personal notes. He translated and adapted them into articles for the TIA website. In these texts fidelity to the original ideas and words is kept as much as possible.

______________________

______________________