Organic Society

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contracts & Honor - II

The Prestige of Honor in Medieval Society

It is easy to understand that a contract is worth the word of those who subscribe to it, and that a society based in large extent on contracts - like medieval society - ends by being a society based on a man’s word of honor, and, therefore, on honor itself. If the contract is the base of society and the base of the contract is honor, the sentiment of honor results in being the very foundation of society.

Then, we understand that veracity, fidelity to keeping one’s word, and a religious respect for everything promised constitute the foundations of the law itself. To the degree that veracity declined, respect given to the word also started to disappear.

In 19th century Brazil, it was common to give a hair of one’s beard as a guarantee of payment for a large debt. After the parties had agreed upon the exchange of a certain sum of money, the one receiving the sum would take a hair from his beard and place it with his signature at the bottom of the document. Or, that thread of hair would simply be given to the creditor, without either document or signature, as a guarantee that after six months or a year the debtor would repay the borrowed sum. The money-lender would keep that hair in an envelope and return it to its owner when the debt was paid.

In 19th century Brazil, it was common to give a hair of one’s beard as a guarantee of payment for a large debt. After the parties had agreed upon the exchange of a certain sum of money, the one receiving the sum would take a hair from his beard and place it with his signature at the bottom of the document. Or, that thread of hair would simply be given to the creditor, without either document or signature, as a guarantee that after six months or a year the debtor would repay the borrowed sum. The money-lender would keep that hair in an envelope and return it to its owner when the debt was paid.

In that epoch, the beard of a man was the symbol of his honor. So, besides giving his word of honor, he would give a part of himself as an assurance that he would repay his debt. In this we still can see the personal warmth of the medieval concept of honor that was alive in society. This ended almost completely in Brazil, however, with the abolition of the monarchy.

The Church had the civil right to forbid scandals

Honor was not conceived in a secular way, but as a religious value, with an important consequence for the Catholic Religion. Honor was a Catholic virtue, and all questions related to honor involved Catholic Morals, which influenced all fields of society.

In passing, let me report a curiosity regarding spiritual honor. The medieval Bishops normally had troops not only to safeguard the Church’s properties, but also to impose Catholic rules regarding questions of dishonor in society relating to the rights of the Church or public offenses against Catholic Morals.

So, if the Bishop were informed that an immoral ball took place one night at a certain neighborhood or that a tavern near a church was attracting customers at the same time of the Mass and diverting people from attending it, he would send his soldiers to bring the person responsible for that ball or tavern before him and forbid him from these practices. If the man did not obey, he would place him in jail for a certain period of time. This was to preserve the honor of the Church and Catholic Morals; it was a part of Ecclesiastical Law accepted by all of society.

So, if the Bishop were informed that an immoral ball took place one night at a certain neighborhood or that a tavern near a church was attracting customers at the same time of the Mass and diverting people from attending it, he would send his soldiers to bring the person responsible for that ball or tavern before him and forbid him from these practices. If the man did not obey, he would place him in jail for a certain period of time. This was to preserve the honor of the Church and Catholic Morals; it was a part of Ecclesiastical Law accepted by all of society.

If an unmarried couple were living publicly a marital life, giving scandal to the people in the local society, the Bishop had the right to call the couple before him and set a deadline for them to end that sinful situation. If they did not comply, they would be expelled from his Diocese or put in jail.

At that time the Church did not exist only to give a spiritual direction, which the person could arbitrarily choose to follow or not. She had the right and obligation to impose the observance of the Commandments of God in everything concerning the honor of the Church or public morality.

How parole worked

It was common in the Middle Ages for prisoners of war to be set at liberty on the one condition that they would give their word of honor to put down their arms and not return to the fight. The prisoner would give his word of honor, surrender his sword as a guarantee, and return to his country, where he would remain for the duration of the war without re-engaging in the fight against that enemy. The prisoners were released on their word of honor.

At other times the King would call a feudal lord before him to impose a penalty for some misbehavior or law-breaking. But, instead of sending him to jail, he would say: “I order you to remain in this or that domicile, but you must give me your word of honor that you will not leave it.” If the feudal lord had no intention to flee, he would make the promise. The King could be absolutely certain that he would not flee.

At other times the King would call a feudal lord before him to impose a penalty for some misbehavior or law-breaking. But, instead of sending him to jail, he would say: “I order you to remain in this or that domicile, but you must give me your word of honor that you will not leave it.” If the feudal lord had no intention to flee, he would make the promise. The King could be absolutely certain that he would not flee.

There were cases where the conqueror offered prisoners the opportunity to live at liberty in a particular city so long as they gave their word of honor that they would not try to escape. One such prisoner made this comment that reveals well the mentality of the time: “From inside a prison I can try to flee, but from my word of honor I cannot. So, I am closer to liberty inside the prison than outside of it after giving my word of honor not to leave it.”

This reveals the great respect a man had for his word. It was this perfume that infused the whole juridical and moral organization of medieval society.

A custom reminiscent of this wholesome past is found in some juridical systems of modern States. It is the type of liberation called parole (in French parole means spoken word), also called conditional freedom. It is a freedom granted by the State to some prisoners who show good behavior and signs of amendment in prison, and do not present a great danger to society. They are granted a conditional freedom or are liberated under parole prior to the completion of the full sentence period. This conditional freedom, however, does not mean that the authorities trust the word of honor of the criminal. It is just a way to diminish the growing population of prisoners by keeping those “under parole” in close vigilance.

Nobility was characterized by honor

For about five centuries, faith and honor were the essential underpinnings of society, the armor of social relationships. When faith and honor were replaced by absolutism in the 16th and principally 17th centuries, society lost those central characteristics. Then, the nobility also lost its essential moral attribute.

Indeed, the nobility was the class that was expected to excel in honor. To be noble and to be honorable were synonymous expressions used in the common language. The noble should be co-naturally honorable and courageous. It was incomprehensible for a noble to be a coward or dishonorable, a man whose word was not trustworthy.

Indeed, the nobility was the class that was expected to excel in honor. To be noble and to be honorable were synonymous expressions used in the common language. The noble should be co-naturally honorable and courageous. It was incomprehensible for a noble to be a coward or dishonorable, a man whose word was not trustworthy.

There was an old saying: “The word of a King can never be reversed.” This could also be said of all those who participated in the King’s authority, that is, all the nobility. The word of a noble was a sacred thing that was never violated.

The idea that the nobles should be models of honor in everything had an interesting expression in civil legislation. The crime of a noble was considered much graver than the same crime committed by a plebeian. For this reason the laws fined the noble much more than the plebeian, charging 20 times more for the same violation.

In the établissements [codes of law] made by St. Louis of France, there was a penalty of a fine of 50 sous [medieval French currency] for a crime; if it were committed by a noble, however, all his properties would be confiscated.

Thus, those who had a greater obligation of honor were more severely punished. This was an application of the principle of the Gospel that to whom more is given, more is demanded (Lk 12:48). In the Judgment, God will be more severe with the powerful. For this reason, on earth the authorities must punish more severely the powerful as well.

Continued

Then, we understand that veracity, fidelity to keeping one’s word, and a religious respect for everything promised constitute the foundations of the law itself. To the degree that veracity declined, respect given to the word also started to disappear.

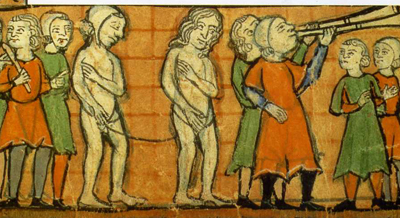

A man returns the money he borrowed; most medieval contracts depended on a man's word

In that epoch, the beard of a man was the symbol of his honor. So, besides giving his word of honor, he would give a part of himself as an assurance that he would repay his debt. In this we still can see the personal warmth of the medieval concept of honor that was alive in society. This ended almost completely in Brazil, however, with the abolition of the monarchy.

The Church had the civil right to forbid scandals

Honor was not conceived in a secular way, but as a religious value, with an important consequence for the Catholic Religion. Honor was a Catholic virtue, and all questions related to honor involved Catholic Morals, which influenced all fields of society.

In passing, let me report a curiosity regarding spiritual honor. The medieval Bishops normally had troops not only to safeguard the Church’s properties, but also to impose Catholic rules regarding questions of dishonor in society relating to the rights of the Church or public offenses against Catholic Morals.

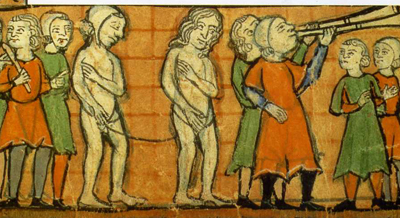

Adulterers exposed to public scorn for their crime against Morals

If an unmarried couple were living publicly a marital life, giving scandal to the people in the local society, the Bishop had the right to call the couple before him and set a deadline for them to end that sinful situation. If they did not comply, they would be expelled from his Diocese or put in jail.

At that time the Church did not exist only to give a spiritual direction, which the person could arbitrarily choose to follow or not. She had the right and obligation to impose the observance of the Commandments of God in everything concerning the honor of the Church or public morality.

How parole worked

It was common in the Middle Ages for prisoners of war to be set at liberty on the one condition that they would give their word of honor to put down their arms and not return to the fight. The prisoner would give his word of honor, surrender his sword as a guarantee, and return to his country, where he would remain for the duration of the war without re-engaging in the fight against that enemy. The prisoners were released on their word of honor.

Prisoners of war were often released on their word of honor

There were cases where the conqueror offered prisoners the opportunity to live at liberty in a particular city so long as they gave their word of honor that they would not try to escape. One such prisoner made this comment that reveals well the mentality of the time: “From inside a prison I can try to flee, but from my word of honor I cannot. So, I am closer to liberty inside the prison than outside of it after giving my word of honor not to leave it.”

This reveals the great respect a man had for his word. It was this perfume that infused the whole juridical and moral organization of medieval society.

A custom reminiscent of this wholesome past is found in some juridical systems of modern States. It is the type of liberation called parole (in French parole means spoken word), also called conditional freedom. It is a freedom granted by the State to some prisoners who show good behavior and signs of amendment in prison, and do not present a great danger to society. They are granted a conditional freedom or are liberated under parole prior to the completion of the full sentence period. This conditional freedom, however, does not mean that the authorities trust the word of honor of the criminal. It is just a way to diminish the growing population of prisoners by keeping those “under parole” in close vigilance.

Nobility was characterized by honor

For about five centuries, faith and honor were the essential underpinnings of society, the armor of social relationships. When faith and honor were replaced by absolutism in the 16th and principally 17th centuries, society lost those central characteristics. Then, the nobility also lost its essential moral attribute.

Councillors participated in the King's authority and honor

There was an old saying: “The word of a King can never be reversed.” This could also be said of all those who participated in the King’s authority, that is, all the nobility. The word of a noble was a sacred thing that was never violated.

The idea that the nobles should be models of honor in everything had an interesting expression in civil legislation. The crime of a noble was considered much graver than the same crime committed by a plebeian. For this reason the laws fined the noble much more than the plebeian, charging 20 times more for the same violation.

In the établissements [codes of law] made by St. Louis of France, there was a penalty of a fine of 50 sous [medieval French currency] for a crime; if it were committed by a noble, however, all his properties would be confiscated.

Thus, those who had a greater obligation of honor were more severely punished. This was an application of the principle of the Gospel that to whom more is given, more is demanded (Lk 12:48). In the Judgment, God will be more severe with the powerful. For this reason, on earth the authorities must punish more severely the powerful as well.

Continued

Posted January 1, 2014

______________________

______________________