Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

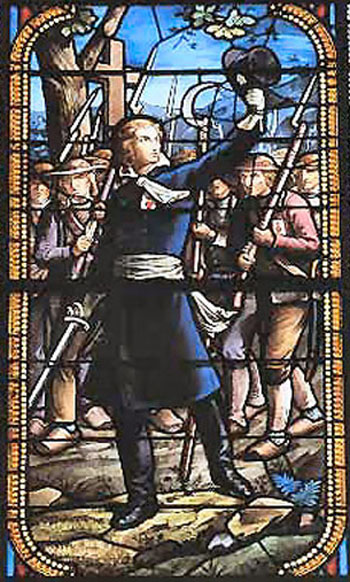

Heroes of La Vendée - IV

The Death of la Rochejaquelein

On the morning of December 4, 1793, the attack upon Angers took place under the Chief General Henri de la Rochejaquelein.

A heavy fire of artillery was continued during the day, but without much result. On the following day cannons were again fired by the Vendéans upon St. Michael's Gate. After some hours of severe fighting a breach was made.

A heavy fire of artillery was continued during the day, but without much result. On the following day cannons were again fired by the Vendéans upon St. Michael's Gate. After some hours of severe fighting a breach was made.

Here, as everywhere else, the soldiers displayed indecision and discouragement. The chiefs gave them a noble example by rushing onwards themselves into the breach. Not a man followed, and all save la Rochejaquelein, Piron and Forestier perished. The remnant of the army retreated to Bauge.

When they had advanced within a short distance of La Fléche, they found the bridge cut down and the opposite shore defended by a strong revolutionary republican force.

La Rochejaquelein, leaving Piron to defend their first position, chose 400 of the cavalry, each of whom took a foot soldier upon his crupper. They rode some distance up the Loire, where they managed to ford the river, their leader going first. They met and surprised the garrison, took the town, regained the bridge, and saved the army by a vigorous charge.

La Rochejaquelein was hailed with acclamation as a great soldier and general, and upon his brow were bound fresh laurels.

The hero alone undismayed

The Vendéans were, however, in terrible straits. No provisions were to be had, and famine was daily and hourly enfeebling the remnants of that once vigorous army. Despair was in every heart and all too plainly written upon every face.

La Rochejaquelein alone, still undismayed, made an assault upon the town of Mans, which he succeeded in taking, and there a small supply of provisions was obtained. He made an effort to reach Ancenis, where he hoped to cross the Loire. He was terribly harassed upon the passage by the republicans.

At Foultourte, a village through which they passed, the revolutionaries, under Marceaux, a celebrated republican leader, supported by Kleber and Westermann, determined to stop the progress of the Vendéans towards Ancenis and cut off the remnant of their army.

At Foultourte, a village through which they passed, the revolutionaries, under Marceaux, a celebrated republican leader, supported by Kleber and Westermann, determined to stop the progress of the Vendéans towards Ancenis and cut off the remnant of their army.

Though fully aware of their slight chance of success, la Rochejaquelein, with his usual energy and presence of mind, made every preparation for a determined resistance. He rallied his troops, especially the cavalry. And, by prayers and entreaties the young leader prevailed upon the fugitives to return and share the fate of their comrades. Taking 3,000 men, he placed them in ambush behind some fir trees, whence they succeeded in repulsing Westermann and Miller.

This effort seemed to have exhausted their remaining strength, and the peasants began to waver. La Rochejaquelein rushed forward, making a desperate charge upon the enemy's centre, but he was not supported. Returning, he called upon the haggard, hollow-eyed men who remained to follow him, besought them in tones of passionate entreaty, or commanded them resolutely and sternly. But all in vain: They suffered him to rush on to the attack almost alone.

Again the heroic chief returned, and made a third and last effort to rouse them; but again without avail. Loyalty, courage, honor, all seemed alike to have deserted the half-starving men.

Hope was dead within their hearts, and again they met with a most disastrous defeat. Having retreated within the walls, they gave themselves up to utter despair.

Again the heroic chief returned, and made a third and last effort to rouse them; but again without avail. Loyalty, courage, honor, all seemed alike to have deserted the half-starving men.

Hope was dead within their hearts, and again they met with a most disastrous defeat. Having retreated within the walls, they gave themselves up to utter despair.

Westermann attacked them at midnight, and their indomitable leader again exhorted them at least to sell their lives dearly. But, alas! They only replied that a few hours longer or shorter mattered not, when they must die.

For the first time positive despair and a sort of frenzy seemed to take possession of la Rochejaquelein. Riding through the streets, he forced a few thousand men to take up arms, but the total want of discipline amongst them neutralized the efforts of their leaders. The battle was both fierce and bloody, but the final blow was dealt to the royalist cause in the Vendée at the Battle of Mans in 1793.

When the Vendéans began their retreat, la Rochejaquelein with other leaders, amongst whom were the afterwards famous Jean Chouan and George Cadoudal, defended the town to the last, and covered the confused flight of their comrades.

Retreat, hiding & a last victory

The royalists hastened on to Ancenis, hoping to cross the Loire. La Rochejaquelein and Stofflet with 18 men made the passage of the river in two frail fishing smacks, their progress being watched with intense eagerness by the entire army. On landing they were attacked by a small force of republicans and compelled to conceal themselves in the heart of the country.

Meanwhile a hostile vessel sailed down the river and sank some rafts on which the Vendéans had hoped to cross. Consternation spread through their ranks. A detachment of the enemy under Westermann came up to enter battle, and an engagement was inevitable.

Meanwhile a hostile vessel sailed down the river and sank some rafts on which the Vendéans had hoped to cross. Consternation spread through their ranks. A detachment of the enemy under Westermann came up to enter battle, and an engagement was inevitable.

The poor broken-spirited peasants, roused by the distant view of their fondly loved Vendée, made one last effort and drove the republicans back. But when the main body of the republican troops arrived, the peasants either fled in dismay or gave themselves up to their foes. Only a mere handful succeeded in crossing the river. Thus were they separated from their leader at the very crisis of their fate.

La Rochejaquelein, having penetrated into the heart of the country, came, after many wanderings, to a farm house in Chatillon, where he took shelter. His adventures at this time remind us rather of those attributed to heroes of romance than of sober reality.

Still fearful of discovery, he was driven to seek an asylum amid the ruins of his ancestral chateau of Durbelières. Here he remained for a considerable time; under cover of the darkness he stole out by night to seek provisions.

In this solitude he continued to devise new plans for a final effort in favor of God, King and Country. For, inspired by the crumbling walls and ancient towers, by the storied tombs of his brave forefathers, he, their worthy descendant, full of indomitable valor, told himself that all was not lost, and that the Vendée should take the field again as the sworn champion of the good cause.

But even in this ruined haunt of the owl and bat, he was not safe. News of his whereabouts having been conveyed to the republican camp hard by, a detachment was sent to make him prisoner. He concealed himself by lying on the entablature of that portion of the façade still remaining. After a hasty search the enemy with drew, and la Rochejaquelein escaped to Poitou, where he joined Charette. ...

La Rochejaquelein gained, soon after his arrival in Poitou, a series of victories over Cordelier. With such forces as he could collect, he entrenched himself in the forest of Vezin. Their numbers were very few, but about that time they took among other prisoners an Adjutant-General of the republican army, upon whom they found an order by which he was commanded to promise the peasants a safe-conduct. Then, after having thus entrapped them, he was ordered to fall upon and slay them. So terrified were these peasants that they flocked to join la Rochejaquelein in great numbers.

La Rochejaquelein gained, soon after his arrival in Poitou, a series of victories over Cordelier. With such forces as he could collect, he entrenched himself in the forest of Vezin. Their numbers were very few, but about that time they took among other prisoners an Adjutant-General of the republican army, upon whom they found an order by which he was commanded to promise the peasants a safe-conduct. Then, after having thus entrapped them, he was ordered to fall upon and slay them. So terrified were these peasants that they flocked to join la Rochejaquelein in great numbers.

Being therefore reinforced and in command of a large army, he attacked General Cordelier at several points, each time defeating him with considerable loss to the republican force. The troops who held the town of Chollet made a sortie with intent to burn the town of Noisailles.

As they were applying their blazing torches to the walls, la Rochejaquelein rode up at the head of a detachment and completely routed them. It was a decisive victory, but the last which la Rochejaquelein was ever to gain for the cause he loved.

Pursuing the fugitives, he discovered two grenadiers hidden behind a hedge. Approaching them, he cried: "Surrender, and you shall have quarter!"

The grenadiers reluctantly acquiesced and were about to give up their arms. But at the moment one of the Vendéan officers, riding up, called his leader by name, imploring him to hold no further parley with the prisoners.

La Rochejaquelein disregarded the advice, and went nearer to question the republicans. As he stooped to seize his musket, one of the grenadiers, taking aim, fired, and the hero fell backwards in his saddle dead.

So perished on the 28th of January, 1794, one of the brightest stars in that immortal galaxy of heroes, which the Vendée and its celebrated struggle produced. ...

He was buried quietly, without pomp or ceremony, so that perchance his death might escape the notice of the republicans, for well they knew the import of such a loss to the cause for which he had given his heart's blood.

He was buried quietly, without pomp or ceremony, so that perchance his death might escape the notice of the republicans, for well they knew the import of such a loss to the cause for which he had given his heart's blood.

His soldiers bore him to a short distance from the place of his death, and there made him a grave where in summertime the grass grew very green and a waving tree played at crossbars with the sunshine.

They laid him down softly and closed his bright eyes, those eyes which had flashed so proudly in the battle's fierce array. They smoothed back the hair from his forehead with almost woman's gentleness. They hung again around his neck the Rosary, which was the distinctive mark of the Catholic and Royal army, together with the scapular worn upon the breast, which they now placed over his quiet heart.

They laid by as a relic the knot of white ribbon, the colors of the cause, which he had ever kept pure and unsullied. With bitter, burning tears they looked their last upon the young and ardent face that had been so loved throughout the Vendée; upon the figure of their boy-hero, who in spite of all obstacles, with an army miserably provisioned and undisciplined, had won them 16 battles within 10 months.

So the soldier of the Vendée was at rest, in the obscure grave wherein his body remained till 1815. It was then exhumed and conveyed to the parish church of Chollet, whence it was again removed. It was finally interred with the bones of his ancestors near the old feudal castle of St. Aubin, where, as a child, he had dreamed boyish dreams of fame and glory. ...

The ancient manor was, as we have seen, destroyed by republican incendiaries. The portraits of his race, in all likelihood, have perished with it. But the portrait of Henri de la Rochejaquelein was preserved even to the smallest details of his personal appearance is enshrined forever in the memory of the people.

The peasant at his peat fire, the noble in his hall, nay, even the very republican, who, we are told, sincerely mourned his death, alike recall with enthusiastic admiration the name and deeds of this noblest of a noble race, Henri, Marquis de la Rochejaquelein, whose short career came to a close while he was still in his 22nd year.

Adapted from Names that Live in Catholic Hearts by Anna Sadlier,

NY: Benzinger Bros, 1882, pp. 220-228.

Posted August 4, 2021

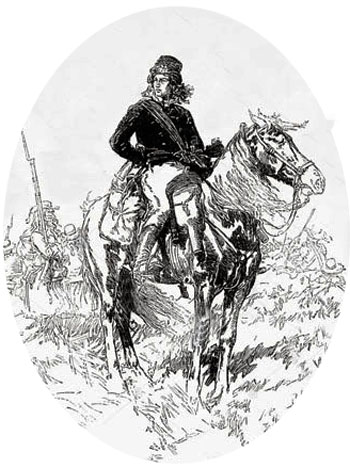

Always at the forefront of the battle

Here, as everywhere else, the soldiers displayed indecision and discouragement. The chiefs gave them a noble example by rushing onwards themselves into the breach. Not a man followed, and all save la Rochejaquelein, Piron and Forestier perished. The remnant of the army retreated to Bauge.

When they had advanced within a short distance of La Fléche, they found the bridge cut down and the opposite shore defended by a strong revolutionary republican force.

La Rochejaquelein, leaving Piron to defend their first position, chose 400 of the cavalry, each of whom took a foot soldier upon his crupper. They rode some distance up the Loire, where they managed to ford the river, their leader going first. They met and surprised the garrison, took the town, regained the bridge, and saved the army by a vigorous charge.

La Rochejaquelein was hailed with acclamation as a great soldier and general, and upon his brow were bound fresh laurels.

The hero alone undismayed

The Vendéans were, however, in terrible straits. No provisions were to be had, and famine was daily and hourly enfeebling the remnants of that once vigorous army. Despair was in every heart and all too plainly written upon every face.

La Rochejaquelein alone, still undismayed, made an assault upon the town of Mans, which he succeeded in taking, and there a small supply of provisions was obtained. He made an effort to reach Ancenis, where he hoped to cross the Loire. He was terribly harassed upon the passage by the republicans.

The Battle of du Mans, a deadly blow

to the royalist cause

Though fully aware of their slight chance of success, la Rochejaquelein, with his usual energy and presence of mind, made every preparation for a determined resistance. He rallied his troops, especially the cavalry. And, by prayers and entreaties the young leader prevailed upon the fugitives to return and share the fate of their comrades. Taking 3,000 men, he placed them in ambush behind some fir trees, whence they succeeded in repulsing Westermann and Miller.

This effort seemed to have exhausted their remaining strength, and the peasants began to waver. La Rochejaquelein rushed forward, making a desperate charge upon the enemy's centre, but he was not supported. Returning, he called upon the haggard, hollow-eyed men who remained to follow him, besought them in tones of passionate entreaty, or commanded them resolutely and sternly. But all in vain: They suffered him to rush on to the attack almost alone.

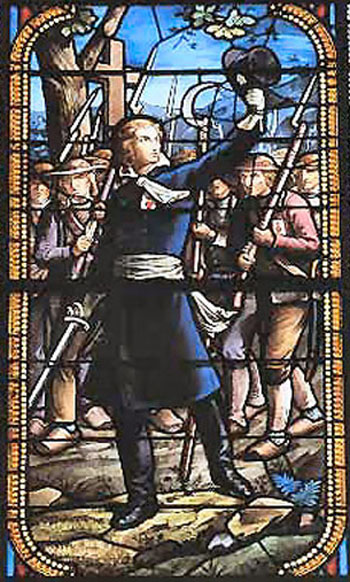

Recreations of scenes from the life of la Rochejaquelein at the ruins of his family castle

Westermann attacked them at midnight, and their indomitable leader again exhorted them at least to sell their lives dearly. But, alas! They only replied that a few hours longer or shorter mattered not, when they must die.

For the first time positive despair and a sort of frenzy seemed to take possession of la Rochejaquelein. Riding through the streets, he forced a few thousand men to take up arms, but the total want of discipline amongst them neutralized the efforts of their leaders. The battle was both fierce and bloody, but the final blow was dealt to the royalist cause in the Vendée at the Battle of Mans in 1793.

When the Vendéans began their retreat, la Rochejaquelein with other leaders, amongst whom were the afterwards famous Jean Chouan and George Cadoudal, defended the town to the last, and covered the confused flight of their comrades.

Retreat, hiding & a last victory

The royalists hastened on to Ancenis, hoping to cross the Loire. La Rochejaquelein and Stofflet with 18 men made the passage of the river in two frail fishing smacks, their progress being watched with intense eagerness by the entire army. On landing they were attacked by a small force of republicans and compelled to conceal themselves in the heart of the country.

In hiding, but still planning new battles & victories

The poor broken-spirited peasants, roused by the distant view of their fondly loved Vendée, made one last effort and drove the republicans back. But when the main body of the republican troops arrived, the peasants either fled in dismay or gave themselves up to their foes. Only a mere handful succeeded in crossing the river. Thus were they separated from their leader at the very crisis of their fate.

La Rochejaquelein, having penetrated into the heart of the country, came, after many wanderings, to a farm house in Chatillon, where he took shelter. His adventures at this time remind us rather of those attributed to heroes of romance than of sober reality.

Still fearful of discovery, he was driven to seek an asylum amid the ruins of his ancestral chateau of Durbelières. Here he remained for a considerable time; under cover of the darkness he stole out by night to seek provisions.

In this solitude he continued to devise new plans for a final effort in favor of God, King and Country. For, inspired by the crumbling walls and ancient towers, by the storied tombs of his brave forefathers, he, their worthy descendant, full of indomitable valor, told himself that all was not lost, and that the Vendée should take the field again as the sworn champion of the good cause.

But even in this ruined haunt of the owl and bat, he was not safe. News of his whereabouts having been conveyed to the republican camp hard by, a detachment was sent to make him prisoner. He concealed himself by lying on the entablature of that portion of the façade still remaining. After a hasty search the enemy with drew, and la Rochejaquelein escaped to Poitou, where he joined Charette. ...

The untimely death of the hero

Being therefore reinforced and in command of a large army, he attacked General Cordelier at several points, each time defeating him with considerable loss to the republican force. The troops who held the town of Chollet made a sortie with intent to burn the town of Noisailles.

As they were applying their blazing torches to the walls, la Rochejaquelein rode up at the head of a detachment and completely routed them. It was a decisive victory, but the last which la Rochejaquelein was ever to gain for the cause he loved.

Pursuing the fugitives, he discovered two grenadiers hidden behind a hedge. Approaching them, he cried: "Surrender, and you shall have quarter!"

The grenadiers reluctantly acquiesced and were about to give up their arms. But at the moment one of the Vendéan officers, riding up, called his leader by name, imploring him to hold no further parley with the prisoners.

La Rochejaquelein disregarded the advice, and went nearer to question the republicans. As he stooped to seize his musket, one of the grenadiers, taking aim, fired, and the hero fell backwards in his saddle dead.

So perished on the 28th of January, 1794, one of the brightest stars in that immortal galaxy of heroes, which the Vendée and its celebrated struggle produced. ...

A quiet burial so his death would escape notice of the revolutionaries for as long as possible

His soldiers bore him to a short distance from the place of his death, and there made him a grave where in summertime the grass grew very green and a waving tree played at crossbars with the sunshine.

They laid him down softly and closed his bright eyes, those eyes which had flashed so proudly in the battle's fierce array. They smoothed back the hair from his forehead with almost woman's gentleness. They hung again around his neck the Rosary, which was the distinctive mark of the Catholic and Royal army, together with the scapular worn upon the breast, which they now placed over his quiet heart.

They laid by as a relic the knot of white ribbon, the colors of the cause, which he had ever kept pure and unsullied. With bitter, burning tears they looked their last upon the young and ardent face that had been so loved throughout the Vendée; upon the figure of their boy-hero, who in spite of all obstacles, with an army miserably provisioned and undisciplined, had won them 16 battles within 10 months.

So the soldier of the Vendée was at rest, in the obscure grave wherein his body remained till 1815. It was then exhumed and conveyed to the parish church of Chollet, whence it was again removed. It was finally interred with the bones of his ancestors near the old feudal castle of St. Aubin, where, as a child, he had dreamed boyish dreams of fame and glory. ...

The ancient manor was, as we have seen, destroyed by republican incendiaries. The portraits of his race, in all likelihood, have perished with it. But the portrait of Henri de la Rochejaquelein was preserved even to the smallest details of his personal appearance is enshrined forever in the memory of the people.

The peasant at his peat fire, the noble in his hall, nay, even the very republican, who, we are told, sincerely mourned his death, alike recall with enthusiastic admiration the name and deeds of this noblest of a noble race, Henri, Marquis de la Rochejaquelein, whose short career came to a close while he was still in his 22nd year.

Adapted from Names that Live in Catholic Hearts by Anna Sadlier,

NY: Benzinger Bros, 1882, pp. 220-228.

Posted August 4, 2021

______________________