Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heroes of La Vendée - III

La Rochejaquelein Is Named

Commander of the Vendée

At the bloody Battle of Cholet in October 1793, the Vendéans sustained a severe defeat and Charles de Bonchamps, the valiant leader of the Vendéans, was mortally wounded. He died the next day. His last act was the pardoning of 5,000 Republican prisoners, whom his troops had sworn to kill in revenge for his death.

Shortly before his death Bonchamps received the Viaticum with extraordinary fervor. He had meted out mercy, and to him was mercy shown when, laying down his command, he appeared before the last tribunal.

Shortly before his death Bonchamps received the Viaticum with extraordinary fervor. He had meted out mercy, and to him was mercy shown when, laying down his command, he appeared before the last tribunal.

Now la Rochejaquelein, at the suggestion of his cousin, the Marquis de Lescure, was chosen commander-in-chief.

With tears in his eyes he refused the honor, begging them to elect one whose years and experience might the more readily inspire confidence. But Lescure persisted in declaring that he alone could restore the fallen fortunes of the Vendée, and the young soldier reluctantly accepted the arduous post of peril and of hardship.

There was little doubt of his ability to fill this important position. In age, it is true, he was the youngest of all the leaders of the insurgence. In judgment and experience he must necessarily have been inferior to many of his seniors; although it is unquestionable that he frequently exhibited the knowledge and military skill of a great general.

In personal courage he was unsurpassed; his valor was reckless, indomitable, and almost superhuman. Yet, once the battle over, none gentler, more humane or generous than he. If he took a prisoner, he at once offered him the chance of single combat; while to the wounded, the dying, the helpless, the oppressed, he was a kind and resolute protector.

In personal courage he was unsurpassed; his valor was reckless, indomitable, and almost superhuman. Yet, once the battle over, none gentler, more humane or generous than he. If he took a prisoner, he at once offered him the chance of single combat; while to the wounded, the dying, the helpless, the oppressed, he was a kind and resolute protector.

In the council-chamber he was modest and even timid; yet on the rare occasions when he proffered advice, it was always good. When he was called upon for his opinion, he invariably replied, "You decide; I will execute."

His motives were pure and lofty. No hope of gain or advancement ever quickened the beatings of his noble heart. His highest ambition was that, in the event of success, the King would give him command of a regiment of Hussars.

By the peasants he was fairly idolized. He was a leader after their own hearts; no royalist chief was ever so beloved as he. Every man would have drawn his sword and spilled his heart's best blood for "Master Henry," as they called him.

Such was the character and such were the qualifications of the man who was now summoned to the chief command of the Vendéan army at the most critical moment of the campaign, when the sturdy hearts of the peasants were beginning to fail them, their arms to grow feeble, and their eyes to lose the olden fire.

The Battle of Laval

The royalists now pressed forward to Laval, defeating a republican force at Chateau-Gonthier on their way thither. A division of the Blues was in position near the city of Laval, and upon it the royalists charged.

The enemy retreated, hotly pursued by la Rochejaquelein, who, in his impetuous ardor, did not perceive that he was alone. He was met in a narrow path by a republican, who at once attacked him with the utmost violence.

The enemy retreated, hotly pursued by la Rochejaquelein, who, in his impetuous ardor, did not perceive that he was alone. He was met in a narrow path by a republican, who at once attacked him with the utmost violence.

La Rochejaquelein was unarmed and partially disabled, one arm being quite helpless from a wound. Evading the blow, the hero rode up at full speed to the republican, threw him to the ground, and cried, whilst he prepared to defend himself against new assailants: "Away, and tell your republicans that the royalist general, without weapons and with one arm disabled, threw you to the ground and then gave you your life."

After which, putting spurs to his horse, he regained the camp.

All this time the republican terror Westermann was upon the track of the royalists. They surprised him about three leagues from Laval, and a severe skirmish took place. The Battle of Laval, which occurred before the heights of Entrames, was one of the most important of the campaign.

On 22 October, the Vendéans reached Laval, defended by 6,000 men. La Rochejaquelein strongly harangued his men, dwelling upon all that could inflame their patriotism or their thirst for glory. He pointed out on the one hand fame and the consciousness of well-doing as their reward, and on the other martyrdom.

The royal forces occupied the heights; the republicans, under Kleberg and Westermann, advanced in formidable array. The engagement took place just below the heights and lasted with determined bravery on both sides for some hours. The Faience men proved most disastrous to the Vendéans.

However, victory finally decided for the royalist, upon the bridge of Chateau Gonthier, despite the gallant efforts of the republican General Bless. The enemy was driven into the river, save a miserable remnant of their army, which took shelter within the walls of Chateau Gonthier.

However, victory finally decided for the royalist, upon the bridge of Chateau Gonthier, despite the gallant efforts of the republican General Bless. The enemy was driven into the river, save a miserable remnant of their army, which took shelter within the walls of Chateau Gonthier.

"What, my friends," cried la Rochejaquelein, "are the conquerors to sleep outside and the vanquished within the walls? We have not finished yet."

In a few hours they had driven the enemy from the town. Towards midnight, however, the Blues made a last effort to retrieve their losses and were finally put to flight. Historians declare that by the skilfull arrangement of his troops, his adroit maneuvers, no less than his wonderful intrepidity, La Rochejaquelein on this occasion displayed the qualities of a great general. ...

Defeat at Granville

A rumor ran through the Vendéan ranks that if they reached a port the English would come to their aid. Their first choice was the port at Saint Malo but they finally fixed on Granville, apparently less well-defended.

On 14 November the Vendéans arrived before the city, but they had no siege equipment and the English had not shown up. Even so, the Vendéans launched an assault and took the outskirts, but their advance was hampered when a great fire broke out.

La Rochejacquelein and other leaders had already begun to climb the rocks at the foot of the ramparts, when cries of "Treason!" began to spread through their ranks, probably shouted by Republican spies. Quickly panic overtook the Vendéans and, as many fled, the assault failed. Having heard no news of the English forces la Rochejaquelein decided to raise the siege.

A skirmish took place at Pontorson, upon which the Vendéans had fallen back. It proved disastrous to the republicans, the Vendéans gaining the day, with considerable loss to the enemy. Here, we are told, friend and foe alike demanded the aids of religion, and the priests hastened hither and thither, administering indiscriminately to republican and royalist.

A skirmish took place at Pontorson, upon which the Vendéans had fallen back. It proved disastrous to the republicans, the Vendéans gaining the day, with considerable loss to the enemy. Here, we are told, friend and foe alike demanded the aids of religion, and the priests hastened hither and thither, administering indiscriminately to republican and royalist.

The Vendéans were now destitute of everything, shoes, clothing, and, worst of all, food. Scores of gallant soldiers died of starvation, and those who survived endured the most terrible hardships. In this condition they were compelled to meet a numerous and well-provisioned army under Kleber and Westermann.

Rallying to the crucifix

The Battle of Dol was a succession of battles in the war in the Vendée. They lasted three days and two nights from November 20-22, 1793, around Dol-de-Bretagne, Pontorson and Antrain.

The republicans, burning to avenge their late defeats, and thirsting for the blood of the Vendéan heroes, precipitated an engagement, which, but for the prudence and foresight of la Rochejaquelein, who drew up his troops in order of battle, would have been fatal to the Catholic army.

The battle commenced soon after midnight. The night was intensely dark, the field was lit only by torches and the flash of artillery and musketry was more appalling in the gloom. Noise and confusion prevailed throughout; it would seem that chaos had again come upon the earth. The courage of the royalists was at its lowest ebb. But their indomitable chief, still full of impetuous valor, sought to communicate to them a spark of his own ardor.

With that wing of the army that was under his command, he succeeded in driving the vanguard of the foe back to Pontorson. Meanwhile Stofflet and Talmont were making a brave resistance. They succeeded, by a vigorous onslaught, in repulsing the republicans. But so terrific was the return charge of the enemy that the royalists were driven back, and even Stofflet compelled to leave the field.

With that wing of the army that was under his command, he succeeded in driving the vanguard of the foe back to Pontorson. Meanwhile Stofflet and Talmont were making a brave resistance. They succeeded, by a vigorous onslaught, in repulsing the republicans. But so terrific was the return charge of the enemy that the royalists were driven back, and even Stofflet compelled to leave the field.

La Rochejaquelein, appearing at the moment, and taking in at a glance the critical situation, rushed into their very midst, shouting the inspiring war-cry and calling upon the terrified peasants to rally. Deaf to every voice but that of fear, the royalists sought only for some means of escape. In their mad terror, women, children, the wounded and the dying were left behind.

At this juncture a venerable priest, the Curé of Sainte Marie-de-Ré, sprang upon a high mound of earth, and holding aloft a large Crucifix, called upon the soldiers to take courage from it. He spoke to them sternly and authoritatively.

"Will you," he cried, "be guilty of the infamy of abandoning your wives and children to the knives of the Blues? Return and fight! It is the only way of saving them. Will you abandon your General in the midst of his foes? Come, my children, I will march at your head with the Crucifix! Kneel down, you who are willing to follow me, and I will give you absolution. If you die, you will go to Heaven; whilst those who betray God and leave their families to perish will go to perdition."

By a spontaneous impulse, 2,000 men knelt to receive the remission of their sins. Then, placing themselves under the standard of La Rochejaquelein, they rushed once more to combat.

"Nous allons en paradis!" " Vive le Roi!" [We are going to Paradise! Long live the King!] rang out in one enthusiastic shout that seemed to pierce the night shadowed heavens.

"Nous allons en paradis!" " Vive le Roi!" [We are going to Paradise! Long live the King!] rang out in one enthusiastic shout that seemed to pierce the night shadowed heavens.

When they reached their hero' s side, he was standing alone, with his arms crossed upon his breast, facing a battery. When he saw that not a man remained by his side, and that resistance was useless, he stood thus, braving death, too proud to turn his back upon the foe.

Never yet in all the fierce ordeals of many battles had he done so, nor would he now commence. News came to him that Talmont was endeavoring to keep another portion of the field with only 800 men. Hastening to his assistance, he succeeded in rallying upon the way a mere handful of men, but they managed to hold their position till the Curé of Sainte Marie came up with his 2,000 followers.

Almost simultaneously Stofflet returned, and the hard-fought field was won by the royal forces. The Curé headed them on their entrance to the town, chanting the "Vexilla Regis," and holding aloft that Crucifix the sight of which had so often inspired the men in the battle's fiercest rage.

This victory was but the beginning of a series of conquests by which the royalists were strengthened and encouraged.

Continued

Adapted from Names that Live in Catholic Hearts by Anna Sadlier,

NY: Benzinger Bros, 1882, pp. 220-228

Posted June 14, 2021

The last order of Bonschamps:

Pardon for the prisoners!

Now la Rochejaquelein, at the suggestion of his cousin, the Marquis de Lescure, was chosen commander-in-chief.

With tears in his eyes he refused the honor, begging them to elect one whose years and experience might the more readily inspire confidence. But Lescure persisted in declaring that he alone could restore the fallen fortunes of the Vendée, and the young soldier reluctantly accepted the arduous post of peril and of hardship.

There was little doubt of his ability to fill this important position. In age, it is true, he was the youngest of all the leaders of the insurgence. In judgment and experience he must necessarily have been inferior to many of his seniors; although it is unquestionable that he frequently exhibited the knowledge and military skill of a great general.

La Rochejacquelein: 'Your decide. I will execute!'

In the council-chamber he was modest and even timid; yet on the rare occasions when he proffered advice, it was always good. When he was called upon for his opinion, he invariably replied, "You decide; I will execute."

His motives were pure and lofty. No hope of gain or advancement ever quickened the beatings of his noble heart. His highest ambition was that, in the event of success, the King would give him command of a regiment of Hussars.

By the peasants he was fairly idolized. He was a leader after their own hearts; no royalist chief was ever so beloved as he. Every man would have drawn his sword and spilled his heart's best blood for "Master Henry," as they called him.

Such was the character and such were the qualifications of the man who was now summoned to the chief command of the Vendéan army at the most critical moment of the campaign, when the sturdy hearts of the peasants were beginning to fail them, their arms to grow feeble, and their eyes to lose the olden fire.

The Battle of Laval

The royalists now pressed forward to Laval, defeating a republican force at Chateau-Gonthier on their way thither. A division of the Blues was in position near the city of Laval, and upon it the royalists charged.

The badge of honoring the Heart of Christ

worn by the Vendéans

La Rochejaquelein was unarmed and partially disabled, one arm being quite helpless from a wound. Evading the blow, the hero rode up at full speed to the republican, threw him to the ground, and cried, whilst he prepared to defend himself against new assailants: "Away, and tell your republicans that the royalist general, without weapons and with one arm disabled, threw you to the ground and then gave you your life."

After which, putting spurs to his horse, he regained the camp.

All this time the republican terror Westermann was upon the track of the royalists. They surprised him about three leagues from Laval, and a severe skirmish took place. The Battle of Laval, which occurred before the heights of Entrames, was one of the most important of the campaign.

On 22 October, the Vendéans reached Laval, defended by 6,000 men. La Rochejaquelein strongly harangued his men, dwelling upon all that could inflame their patriotism or their thirst for glory. He pointed out on the one hand fame and the consciousness of well-doing as their reward, and on the other martyrdom.

The royal forces occupied the heights; the republicans, under Kleberg and Westermann, advanced in formidable array. The engagement took place just below the heights and lasted with determined bravery on both sides for some hours. The Faience men proved most disastrous to the Vendéans.

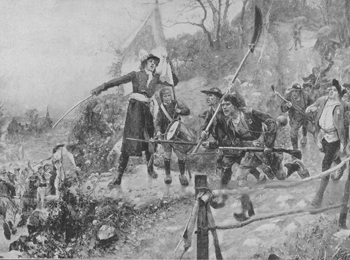

La Rochejacquelein rallies the troops

"What, my friends," cried la Rochejaquelein, "are the conquerors to sleep outside and the vanquished within the walls? We have not finished yet."

In a few hours they had driven the enemy from the town. Towards midnight, however, the Blues made a last effort to retrieve their losses and were finally put to flight. Historians declare that by the skilfull arrangement of his troops, his adroit maneuvers, no less than his wonderful intrepidity, La Rochejaquelein on this occasion displayed the qualities of a great general. ...

Defeat at Granville

A rumor ran through the Vendéan ranks that if they reached a port the English would come to their aid. Their first choice was the port at Saint Malo but they finally fixed on Granville, apparently less well-defended.

On 14 November the Vendéans arrived before the city, but they had no siege equipment and the English had not shown up. Even so, the Vendéans launched an assault and took the outskirts, but their advance was hampered when a great fire broke out.

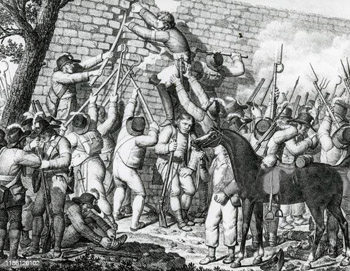

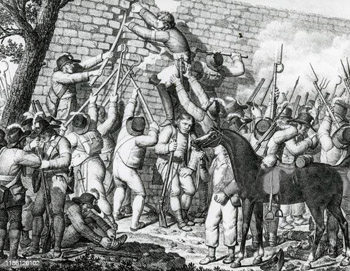

La Rochejacquelein and other leaders had already begun to climb the rocks at the foot of the ramparts, when cries of "Treason!" began to spread through their ranks, probably shouted by Republican spies. Quickly panic overtook the Vendéans and, as many fled, the assault failed. Having heard no news of the English forces la Rochejaquelein decided to raise the siege.

Betrayal & a fire end the siege of Granville

The Vendéans were now destitute of everything, shoes, clothing, and, worst of all, food. Scores of gallant soldiers died of starvation, and those who survived endured the most terrible hardships. In this condition they were compelled to meet a numerous and well-provisioned army under Kleber and Westermann.

Rallying to the crucifix

The Battle of Dol was a succession of battles in the war in the Vendée. They lasted three days and two nights from November 20-22, 1793, around Dol-de-Bretagne, Pontorson and Antrain.

The republicans, burning to avenge their late defeats, and thirsting for the blood of the Vendéan heroes, precipitated an engagement, which, but for the prudence and foresight of la Rochejaquelein, who drew up his troops in order of battle, would have been fatal to the Catholic army.

The battle commenced soon after midnight. The night was intensely dark, the field was lit only by torches and the flash of artillery and musketry was more appalling in the gloom. Noise and confusion prevailed throughout; it would seem that chaos had again come upon the earth. The courage of the royalists was at its lowest ebb. But their indomitable chief, still full of impetuous valor, sought to communicate to them a spark of his own ardor.

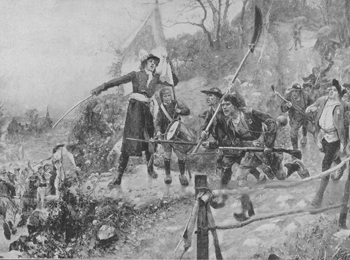

La Rochejacquelein, always the first

to breach the walls or enter combat

La Rochejaquelein, appearing at the moment, and taking in at a glance the critical situation, rushed into their very midst, shouting the inspiring war-cry and calling upon the terrified peasants to rally. Deaf to every voice but that of fear, the royalists sought only for some means of escape. In their mad terror, women, children, the wounded and the dying were left behind.

At this juncture a venerable priest, the Curé of Sainte Marie-de-Ré, sprang upon a high mound of earth, and holding aloft a large Crucifix, called upon the soldiers to take courage from it. He spoke to them sternly and authoritatively.

"Will you," he cried, "be guilty of the infamy of abandoning your wives and children to the knives of the Blues? Return and fight! It is the only way of saving them. Will you abandon your General in the midst of his foes? Come, my children, I will march at your head with the Crucifix! Kneel down, you who are willing to follow me, and I will give you absolution. If you die, you will go to Heaven; whilst those who betray God and leave their families to perish will go to perdition."

By a spontaneous impulse, 2,000 men knelt to receive the remission of their sins. Then, placing themselves under the standard of La Rochejaquelein, they rushed once more to combat.

La Rochejacquelein, beloved by the peasants

When they reached their hero' s side, he was standing alone, with his arms crossed upon his breast, facing a battery. When he saw that not a man remained by his side, and that resistance was useless, he stood thus, braving death, too proud to turn his back upon the foe.

Never yet in all the fierce ordeals of many battles had he done so, nor would he now commence. News came to him that Talmont was endeavoring to keep another portion of the field with only 800 men. Hastening to his assistance, he succeeded in rallying upon the way a mere handful of men, but they managed to hold their position till the Curé of Sainte Marie came up with his 2,000 followers.

Almost simultaneously Stofflet returned, and the hard-fought field was won by the royal forces. The Curé headed them on their entrance to the town, chanting the "Vexilla Regis," and holding aloft that Crucifix the sight of which had so often inspired the men in the battle's fiercest rage.

This victory was but the beginning of a series of conquests by which the royalists were strengthened and encouraged.

Continued

Adapted from Names that Live in Catholic Hearts by Anna Sadlier,

NY: Benzinger Bros, 1882, pp. 220-228

Posted June 14, 2021

______________________

______________________