About the Church

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Authority of Pontifical & Conciliar Documents – III

Infallibility & Continuity of the Magisterium

Vatican Council I did not declare under what conditions an Ecumenical Council is infallible. But, through analogy with the Papal Magisterium, it can be affirmed that the conditions for the Extraordinary Universal Magisterium are the same four applied to the Extraordinary Pontifical Magisterium. Like the Pope, the Council has the power to be infallible, a power that it may or may not use it as it pleases.

Many misinformed Catholics might object and affirm that they have always heard that every Ecumenical Synod is necessarily infallible. This is not, however, what theologians say.

St. Robert Bellarmine explains that it is only by the words of the Council that one can know if its decrees are proffered as infallible. He concludes that, when the wording is unclear in this regard, it is not certain that its teaching is de fide (De Conc., 2, 12). And, if not clear, it is not dogma, for, according to the Code of Canon Law [of 1917], “No truth should be taken as stated or defined as dogma unless it is manifestly stated” (can. 1323, § 3). (1)

St. Robert Bellarmine explains that it is only by the words of the Council that one can know if its decrees are proffered as infallible. He concludes that, when the wording is unclear in this regard, it is not certain that its teaching is de fide (De Conc., 2, 12). And, if not clear, it is not dogma, for, according to the Code of Canon Law [of 1917], “No truth should be taken as stated or defined as dogma unless it is manifestly stated” (can. 1323, § 3). (1)

An exhaustive study of the Extraordinary Universal Magisterium should include the analysis of numerous problems that lie outside the limits of this series. In order to give the reader a broader view of the subject, albeit brief, we present here some theses accepted without discussion among non-progressivist theologians:

The Ordinary Magisterium, whether Papal or Universal, cannot be defined as a teaching that does not enjoy the note of infallibility.

It is true that by itself, that is, isolated from the whole, a teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium does not involve infallibility. Thus, when St. Pius X's Encyclical Ad diem illum defends the Co-Redemption of Our Lady, it does not speak in a way that implies pontifical infallibility. In this case we are, therefore, far removed from a solemn definition, such as the Bull Ineffabilis Deus, which defined the Immaculate Conception and which in itself would close the issue, even if there were no other papal pronouncements on the topic.

However, there is another way where the Ordinary Magisterium may involve infallibility. For example, in dealing with the Co-Redemption, Jesuit Fr. J. A. Aldama states:

However, there is another way where the Ordinary Magisterium may involve infallibility. For example, in dealing with the Co-Redemption, Jesuit Fr. J. A. Aldama states:

“Although the Ordinary Magisterium of the Roman Pontiff is not infallible per se, if, however, it teaches constantly and for a long time a certain doctrine to the whole Church, as occurs in our case [of the Co-Redemption], its infallibility must be absolutely admitted, otherwise it would lead the Church into error.” (4)

Therefore, according to Fr. Aldama, Mary as Co-Redeemer is a doctrine already infallibly taught by the Church, although it has not yet been the object of any pronouncement of the Extraordinary Magisterium, either Papal or Universal.

Here, we have the infallibility of the Ordinary Magisterium by means of the continuity of one same teaching. This is a very important principle, which many Catholics often forget when studying our Faith. (5)

The doctrinal foundation of this title of infallibility is what Fr. Aldama points out to us: if, in a long and uninterrupted series of ordinary teaching documents on one point, the Popes and the Universal Church could be mistaken, then the gates of Hell would have prevailed against the Bride of Christ. The Church would have become a teacher of errors, whose dangerous and even ominous influence the faithful could not escape.

What length of time is required for a certain truth to be considered infallible by means of the continuity of the ordinary Magisterium? It is puerile to imagine one can decide such matters with an hourglass. Living facts are not measured by computers, but by common sense, which is the only instrument capable of weighing the imponderables. And the facts of faith – which are not only living but supernatural – are only measured by Catholic sense, inspired by grace.

Factors that influence the establishment of continuity

It is obvious that time is not the only factor to be taken into account in this matter. There are a number of others, some of which we will indicate to give a general orientation to the reader, without aiming for an exhaustive enumeration. Nor will we make a detailed analysis of the factors indicated, and much less set out the collateral questions that each might suggest, as this would extend beyond the narrow limits of this series.

* The importance that the Pope gives to the document. If this emphasis is great, the pronouncement will have a much greater weight in establishing a continuity of doctrine, versus a teaching that has been the object of little insistence and emphasis on the part of the Pontiff.

* The importance that the Pope gives to the document. If this emphasis is great, the pronouncement will have a much greater weight in establishing a continuity of doctrine, versus a teaching that has been the object of little insistence and emphasis on the part of the Pontiff.

* The importance that later Popes give to the document. Very often the Supreme Pontiffs quote their Predecessors, repeat what they have taught and praise their documents. Such a practice, which might seem to be a protocol or a mere manifestation of respect, is nevertheless of great importance in establishing the continuity of a teaching. For it clearly establishes that the later Pope wanted to follow the same path as his Predecessor.

* The solemnity of the pronouncement. An Encyclical or a Conciliar Constitution, for example, has more weight than a single Speech pronounced by the Pope at a public audience.

* The universality of the teaching. The catechism classes given by St. Pius X to the people of Rome and to the pilgrims have less authority than the Christmas Radio Messages that Pius XII addressed each year to the Catholic world.

* The audience to which the Pope speaks. Speeches addressed to scientific congresses, for example, are particularly important, given the high technical level of the audience. Such congresses are sometimes speaker box for the Pontiff's voice, intended to extend, articulate and spread his words throughout the world. Thus, the repercussion of the discourses of Pius XII on anti-contraceptive methods addressed to congresses of midwives, hematologists, etc. was enormous.

* The attention given by theologians to the pronouncement. The theologians, who are doctors of the sacred sciences, are charged by the Church to systematize and teach her doctrine. If a large number of them misunderstood the scope of a conciliar or papal declaration, the latter would presumably correct them by making a new pronouncement. Thus, if a certain doctrine coming from pontifical documents is repeated extensively by theologians under the complacent silence of the Pope, it becomes clear that the latter not only professes that teaching, but also wants it to be broadly spread throughout the Church.

* The attention given by theologians to the pronouncement. The theologians, who are doctors of the sacred sciences, are charged by the Church to systematize and teach her doctrine. If a large number of them misunderstood the scope of a conciliar or papal declaration, the latter would presumably correct them by making a new pronouncement. Thus, if a certain doctrine coming from pontifical documents is repeated extensively by theologians under the complacent silence of the Pope, it becomes clear that the latter not only professes that teaching, but also wants it to be broadly spread throughout the Church.

* The repercussion of the document in the Catholic world in general. The argument just given is valid not only for theologians but, mutatis mutandis, for Catholic circles in general. If a pontifical or conciliar statement receives a warm welcome in the political milieu, the media, religious associations, etc., and if the Pope is silent, it is because he wants to see it widely disseminated.

* A teaching that has long been accepted without discussion throughout the Catholic world easily acquires the characteristic of infallible teaching. According to the classic formula of St. Vincent de Lerins, we must believe what has been taught always, everywhere and by all: “quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus.” For the assistance of the Divine Holy Spirit would be flawed if a doctrine taught under these three conditions could be false. It is necessary, however, not to accept the adage exclusively, that is, as if the infallibility through the continuity of the same teaching only existed when those three conditions were met. (6)

* The uninterrupted character of the series. If a doctrine of several Popes is contradicted by one of their Successors, or by a Council, before it is constituted as infallible teaching, it is clear that the series is broken. This negative factor may have a significant influence on the establishment of continuity.

Is it possible for any papal or conciliar document to be in direct opposition to infallible teachings of the past? It is obvious that, if the new statement is also infallible, no such opposition can exist.

Is it possible for any papal or conciliar document to be in direct opposition to infallible teachings of the past? It is obvious that, if the new statement is also infallible, no such opposition can exist.

However, prominent scholars – such as St. Robert Bellarmine, Suarez, Cano and Soto – consider such a hypothesis as theologically possible. And it is evident that in such a case the Catholic should then remain faithful to the infallible doctrine. This hypothesis would bring scholars to the multi-century question, one in which the greatest theologians of modern times have especially been engaged, which is the possibility of a heretic Pope. (7)

* The importance of the thesis in the document. The central theme – of an Encyclical, for example – implies more pontifical authority than a hasty statement about a secondary thesis.

* The way the document presents the subject. In Quadragesimo anno, Pope Pius XI states that he will answer questions received by the Holy See about the non-Catholic character of Socialism. This gives particular importance to this part of the document, as it highlights the purpose of resolving doctrinal issues with papal authority.

The works of Archbishop Paul Nau (8) make a detailed study of these various factors that can influence the establishment of the continuity of a teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium.

An example: private property

It seems to us unquestionable that the principles set forth by theologians regarding the infallibility through the continuity of the same teaching apply to the fundamental points of the doctrine of private property.

There is a striking number of papal documents that, over the course of a century and a half, have uninterruptedly taught that private property is according to Natural Law and have condemned Socialism. (9) These documents have resonated throughout the Church: It is enough to recall Rerum novarum and Quadragesimo anno.

How can one maintain that this series of teachings on private property is any less rich than those of Mary as Co-Redeemer, which, according to Fr. Aldama, is no longer a matter of free discussion for Catholics?

Continued

Many misinformed Catholics might object and affirm that they have always heard that every Ecumenical Synod is necessarily infallible. This is not, however, what theologians say.

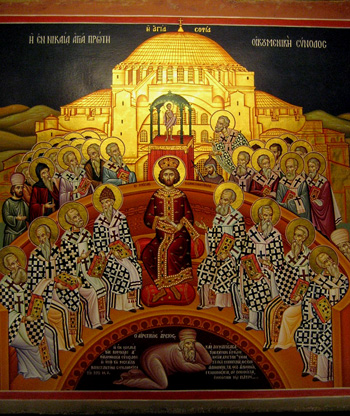

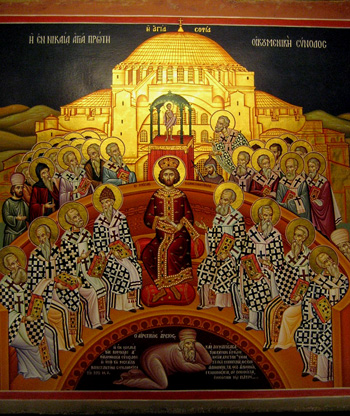

The Council of Nicaea, with Arius depicted as defeated, definitely set out the Creed

An exhaustive study of the Extraordinary Universal Magisterium should include the analysis of numerous problems that lie outside the limits of this series. In order to give the reader a broader view of the subject, albeit brief, we present here some theses accepted without discussion among non-progressivist theologians:

- Council decisions can never be infallible unless they have been approved by the Pope.

- A Council is infallible only in those matters which it clearly imposes something as [a doctrine] to be believed. (2)

- The Councils of Trent and Vatican I wanted to define not only in their canons, but also in their doctrinal chapters. (3)

The Ordinary Magisterium, whether Papal or Universal, cannot be defined as a teaching that does not enjoy the note of infallibility.

It is true that by itself, that is, isolated from the whole, a teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium does not involve infallibility. Thus, when St. Pius X's Encyclical Ad diem illum defends the Co-Redemption of Our Lady, it does not speak in a way that implies pontifical infallibility. In this case we are, therefore, far removed from a solemn definition, such as the Bull Ineffabilis Deus, which defined the Immaculate Conception and which in itself would close the issue, even if there were no other papal pronouncements on the topic.

Although not officially declared dogma, Mary as Co-Redeemer is a doctrine already infallibly taught by the Church

“Although the Ordinary Magisterium of the Roman Pontiff is not infallible per se, if, however, it teaches constantly and for a long time a certain doctrine to the whole Church, as occurs in our case [of the Co-Redemption], its infallibility must be absolutely admitted, otherwise it would lead the Church into error.” (4)

Therefore, according to Fr. Aldama, Mary as Co-Redeemer is a doctrine already infallibly taught by the Church, although it has not yet been the object of any pronouncement of the Extraordinary Magisterium, either Papal or Universal.

Here, we have the infallibility of the Ordinary Magisterium by means of the continuity of one same teaching. This is a very important principle, which many Catholics often forget when studying our Faith. (5)

The doctrinal foundation of this title of infallibility is what Fr. Aldama points out to us: if, in a long and uninterrupted series of ordinary teaching documents on one point, the Popes and the Universal Church could be mistaken, then the gates of Hell would have prevailed against the Bride of Christ. The Church would have become a teacher of errors, whose dangerous and even ominous influence the faithful could not escape.

What length of time is required for a certain truth to be considered infallible by means of the continuity of the ordinary Magisterium? It is puerile to imagine one can decide such matters with an hourglass. Living facts are not measured by computers, but by common sense, which is the only instrument capable of weighing the imponderables. And the facts of faith – which are not only living but supernatural – are only measured by Catholic sense, inspired by grace.

Factors that influence the establishment of continuity

It is obvious that time is not the only factor to be taken into account in this matter. There are a number of others, some of which we will indicate to give a general orientation to the reader, without aiming for an exhaustive enumeration. Nor will we make a detailed analysis of the factors indicated, and much less set out the collateral questions that each might suggest, as this would extend beyond the narrow limits of this series.

Paul VI breaks tradition and welcomes Schismatic Militon with a gift at Vatican II

* The importance that later Popes give to the document. Very often the Supreme Pontiffs quote their Predecessors, repeat what they have taught and praise their documents. Such a practice, which might seem to be a protocol or a mere manifestation of respect, is nevertheless of great importance in establishing the continuity of a teaching. For it clearly establishes that the later Pope wanted to follow the same path as his Predecessor.

* The solemnity of the pronouncement. An Encyclical or a Conciliar Constitution, for example, has more weight than a single Speech pronounced by the Pope at a public audience.

* The universality of the teaching. The catechism classes given by St. Pius X to the people of Rome and to the pilgrims have less authority than the Christmas Radio Messages that Pius XII addressed each year to the Catholic world.

* The audience to which the Pope speaks. Speeches addressed to scientific congresses, for example, are particularly important, given the high technical level of the audience. Such congresses are sometimes speaker box for the Pontiff's voice, intended to extend, articulate and spread his words throughout the world. Thus, the repercussion of the discourses of Pius XII on anti-contraceptive methods addressed to congresses of midwives, hematologists, etc. was enormous.

JPII relies on Gaudium et spes to make an unprecedented visit to the Rome Synagogue

* The repercussion of the document in the Catholic world in general. The argument just given is valid not only for theologians but, mutatis mutandis, for Catholic circles in general. If a pontifical or conciliar statement receives a warm welcome in the political milieu, the media, religious associations, etc., and if the Pope is silent, it is because he wants to see it widely disseminated.

* A teaching that has long been accepted without discussion throughout the Catholic world easily acquires the characteristic of infallible teaching. According to the classic formula of St. Vincent de Lerins, we must believe what has been taught always, everywhere and by all: “quod semper, quod ubique, quod ab omnibus.” For the assistance of the Divine Holy Spirit would be flawed if a doctrine taught under these three conditions could be false. It is necessary, however, not to accept the adage exclusively, that is, as if the infallibility through the continuity of the same teaching only existed when those three conditions were met. (6)

* The uninterrupted character of the series. If a doctrine of several Popes is contradicted by one of their Successors, or by a Council, before it is constituted as infallible teaching, it is clear that the series is broken. This negative factor may have a significant influence on the establishment of continuity.

Francis breaks with teaching on divorced and remarried persons receiving Communion, causing confusion

However, prominent scholars – such as St. Robert Bellarmine, Suarez, Cano and Soto – consider such a hypothesis as theologically possible. And it is evident that in such a case the Catholic should then remain faithful to the infallible doctrine. This hypothesis would bring scholars to the multi-century question, one in which the greatest theologians of modern times have especially been engaged, which is the possibility of a heretic Pope. (7)

* The importance of the thesis in the document. The central theme – of an Encyclical, for example – implies more pontifical authority than a hasty statement about a secondary thesis.

* The way the document presents the subject. In Quadragesimo anno, Pope Pius XI states that he will answer questions received by the Holy See about the non-Catholic character of Socialism. This gives particular importance to this part of the document, as it highlights the purpose of resolving doctrinal issues with papal authority.

The works of Archbishop Paul Nau (8) make a detailed study of these various factors that can influence the establishment of the continuity of a teaching of the Ordinary Magisterium.

An example: private property

It seems to us unquestionable that the principles set forth by theologians regarding the infallibility through the continuity of the same teaching apply to the fundamental points of the doctrine of private property.

There is a striking number of papal documents that, over the course of a century and a half, have uninterruptedly taught that private property is according to Natural Law and have condemned Socialism. (9) These documents have resonated throughout the Church: It is enough to recall Rerum novarum and Quadragesimo anno.

How can one maintain that this series of teachings on private property is any less rich than those of Mary as Co-Redeemer, which, according to Fr. Aldama, is no longer a matter of free discussion for Catholics?

Continued

- See also Sisto Cartechini, "Dall'Opinione al Domma," in La Civiltà Cattolica, Roma, 1953, p. 26.

- Cf. St. Roberto Bellarmino, De Conc., in Opera Omnia, Mediolani: Natale Battezzati, 1857, vol. 2, 2, 12.

- Cf. Ioachim Salaverri, "De Ecclesia Christi" in Sacrae Theologiae Summa, Madrid: BAC, 1958, vol p. 816.

- Josephus A. de Aldama, SJ, "Mariologia," in Sacrae Theologiae Summa, Madrid: B.A.C., 1961, vol. III. p. 418.

- See also Paul Nau, Une Source Doctrinale: les Encycliques, Paris: Les Éditions du Cèdre, 1952, pp. 68 ff., and "El Magisterio Pontificio Ordinario, Lugar Teológico" in Verbo, Madrid, n. 14, pp. 47 ff.

- Cf. Diekamp, p. 68.

- See, Adrian II, Allocutio 3 lecta in Concilio VIII Act. 7, apud Hefele-Leclercq, Histoire des Conciles, Letouzey, 1911, vol. IV, pp. 471-472; Innocent III, "Sermo IV in consecratione Pontificis," in Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 217, col. 670; St. Robert Bellarmine, De Romano Pontifice in Opera Omnia, Mediolani: Natale Battezzati, 1857, vol. 2, 30; 4,6 ff; Franciscus Suarez, "De Fide", disp. X in Opera Omnia, Paris: Vivès, 1858, vol. X, s. 6; "De Legibus", in ibid., lib. 4, cap. 7; Melchior Cano, Opera, cap. postr. Venetiis, 1776, lib. IV, ad 12; Domingo Soto, "Commentarium Fratris Dominici Soto Segobiensis" in Quartum Sententiarum, Salmanticae, 1561, vol. I, d. 22, q. 2, a. 2; St. Alphonsus Liguori, Oeuvres Dogmatiques, édition Casterman, vol. IX, p. 232, apud J. Berthier, Abrégé de Théologie Dogmatique et Morale, Lyon-Paris, Vitte, 1927, p. 232; Jayme Balmes, Protestantismo Comparado com o Catolicismo em suas Relações com a Civilização Européia, Porto-Braga: Livraria Internacional, 1877, vol. IV, pp. 78-79; Ludovicus Billot, Tractatus de Ecclesia Christi, Prati, Giachetti, 1909, vol. I. pp. 609ff; Franciscus Xavier Wernz — Petrus Vidal, Ius Canonicum, Romae: Universitas Gregoriana, 1943, vol. II, pp. 517ff.; Antonius Straub, De Ecclesia Christi, Oeniponte, L. Puster, 1912, vol. II., p. 480; E. Dublanchy, entry "Infaillibilité du Pape," in Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, vol. VI, col. 1714; Joachim Salaverri, "De Ecclesia Christi," in Sacrae Theologiae Summa, Madrid: B.A.C., 1958, vol. I, pp. 698, 718; Charles Journet, L'Eglise du Verbe Incarné, Fribourg: Desclée, 1962, vol. I, pp. 625ff; vol. II, pp. 1063ff; Hans Kung, Structures de l'Eglise, Paris: Desclée, 1963, pp. 292ff; V. Mondello, "La Dottrina del Gaetano sul Romano Pontefice," apud, Messina, 1965 summary in La Civiltà Cattolica, 4 giugno 1966, pp. 470-471.

- Cf. Paul Nau, Une Source Doctrinale and El Magisterio Pontificio Ordinario.

- Cf. Geraldo de Proença Sigaud — Antonio de Castro Mayer — Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira — Luiz Mendonça de Freitas, Reforma Agrária — Questão de Consciência, São Paulo: Editora Vera Cruz, 4a. ed., 1962, pp. 38ff.)

First published in Catolicísmo, n.. 202, October 1967

Posted September 23, 2019

Posted September 23, 2019