Catholic Customs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Golden Nights

The nine nights between December 17 and December 24 are referred to as the "Golden Nights," when the Church recites the

O Antiphons during Vespers.

These days were especially related to Our Lady and her Expectation of the birth of Our Lord throughout Central Europe and Spain. The Church in Spain and France even established a special feast observed as the Feast of the Expectation on December 18.

These days were especially related to Our Lady and her Expectation of the birth of Our Lord throughout Central Europe and Spain. The Church in Spain and France even established a special feast observed as the Feast of the Expectation on December 18.

Rome gave special permission for priests to celebrate the "Golden Mass," or "Rorate Mass" of Ember Wednesday, before daybreak on these nine days preceding Christmas. The name "Rorate" comes from the first words of the Introit of the Mass: "Rorate Caeli." (Drop down ye Heavens from above)

In some countries, these early Masses were an ancient custom said every morning from the first Sunday of Advent until Christmas Eve.

The Catholic peoples of old awoke long before dawn and walked to church on these mornings, carrying their lanterns. The darkness spoke to them of the darkness of the world before Jesus, the Lght of the world, was born and of the need to prepare for the Day of Judgment when Christ would come again.

Because of the intense darkness during this time of the year, many peoples believed that evil spirits roamed more freely – only to be dispelled by signs of the approaching Holiest Night of the Year.

When the English people heard the cock crowing on the dark nights of November or December, they believed that the cock was scaring away the evil spirits to prepare for the coming of the Christ Child. At the sound of the bird, they would exclaim, "The cock is crowing for Christmas!" (Curiosities)

The Hungarians believed that witches roamed freely throughout the land during these dark nights and were only dispersed by the tolling of the bells announcing the Rorate Mass.

The Hungarians believed that witches roamed freely throughout the land during these dark nights and were only dispersed by the tolling of the bells announcing the Rorate Mass.

The Poles developed the custom of placing seven candles on the altar with the middle candle raised above the others to symbolize Our Lady. This custom originated in the 1200s by a man of Poznan.

The King admired the custom and introduced it at the Royal Cathedral. During the Rorate Mass, he walked to the altar and lit the highest candle, after which he said aloud, "I am ready for the Judgment Day." He was followed by six other men each representing a different social rank: archbishop, senator, nobleman, soldier, merchant and peasant. (Polish Customs, Traditions, & Folklore, Sophie Hodorowicz Knabpg, p. 23)

This custom illustrates well how every Medieval Catholic – were he king or beggar – was aware that he would have to appear before the Judgment Seat to give an account for his deeds. The Catholic truth and customs created a bond of unity – unheard of in Modern Times – as each Catholic prepared in Advent of the coming of Christ and of the dread Judgment Day.

Baking & preparing for Christmas

Catholic peoples understood that preparing for a great feast required a physical as well as a spiritual cleansing. In every land, housewives cleaned the house thoroughly during the week before Christmas to insure that everything was ready for the great Feast.

The silver and china were polished until they shone, the chimney was swept, the best linens were washed for the Christmas Table, and the holy images and statues were carefully cleaned. Everything had to be at its best and most brilliant for the coming of the King of Kings.

The silver and china were polished until they shone, the chimney was swept, the best linens were washed for the Christmas Table, and the holy images and statues were carefully cleaned. Everything had to be at its best and most brilliant for the coming of the King of Kings.

The arrival of the first night of the O Antiphons on December 17 was a signal for housewives from Scandinavia to Greece to begin to bake their traditional Christmas breads, cakes, cookies and pies. Each region had its particular date on which certain Christmas foods should be baked.

English housewives began to bake Mincemeat pies on December 16. Austrian housewives baked the Kletzenbrot (a dried fruit-filled bread) on the Feast of St. Thomas (December 21). One large loaf was made and then smaller loaves made for each member of the family. All of these breads and cakes were placed in safe keeping to be eaten at the Christmas Eve feast and on Christmas morning.

In Tyrol and Canada, St. Thomas's Day was the traditional day to bake meat pies to be frozen and saved for the

Feast of the Epiphany.

In Tyrol and Canada, St. Thomas's Day was the traditional day to bake meat pies to be frozen and saved for the

Feast of the Epiphany.

In Bavaria, Austria, and Hungary, where it was traditional to eat roast pork on Christmas Day, the men would slaughter the family pig on the Feast of St. Thomas and prepare the "Christmas pig" (Weihnachter) for the feast. Sometimes mischievous young men would attempt to steal the pig's head – or the whole pig – from a neighbor; if the culprit was caught he would be obliged to offer drinks to the whole family as a recompense.

During this Octave before Christmas, monks in medieval monasteries would receive extra treats or gifts each day. At the Saint Benedict Abbey of Fleury (now Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire), the antiphons were recited each day by monks of different rank beginning with the Abbott.

When the chanting was finished, one monk would offer a gift to each of his fellow monks. Often the gift would be associated with the antiphon of the day.

When the chanting was finished, one monk would offer a gift to each of his fellow monks. Often the gift would be associated with the antiphon of the day.

The monk assigned to December 19 might have been the gardener so that he could give a gift from the garden in honor of Our Lord the "Root of Jesse" (O Radix Jesse). The Abbott would always give the gifts on the last day of the O Antiphons (December 23), and his gifts were often very generous.

Medieval expense records show that the foodstuff the Abbott brought to the table on this day of the Expectation were no meager gifts..

Restoring the customs

Today's Catholics should strive to be more medieval in spirit as they prepare for Christmas. The house should be cleaned, silver polished, Christmas breads, cakes and cookies baked and all other necessary preparations made as the great feast draws near.

The O Antiphons would make a fitting addition to the evening prayers of the day, since it is always efficacious to unite with the prayers of the Church. These solemn antiphons used to resound through every church on the evenings preceding Christmas, solemn reminders of the majesty of He who is to come.

If Catholics today were to restore the ancient solemnities and expectation in preparing for the great feast of Christmas in a worthy manner, they could say with the Poles of old, "I, too, am ready for the Judgment Day."

Posted December 16, 2020

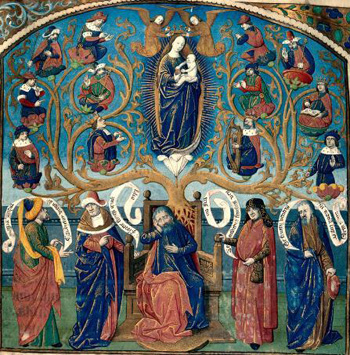

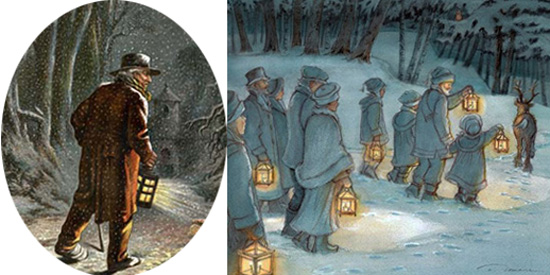

The Jesse Tree, fitting for the Antiphon O Radix Jesse on December 19

Rome gave special permission for priests to celebrate the "Golden Mass," or "Rorate Mass" of Ember Wednesday, before daybreak on these nine days preceding Christmas. The name "Rorate" comes from the first words of the Introit of the Mass: "Rorate Caeli." (Drop down ye Heavens from above)

In some countries, these early Masses were an ancient custom said every morning from the first Sunday of Advent until Christmas Eve.

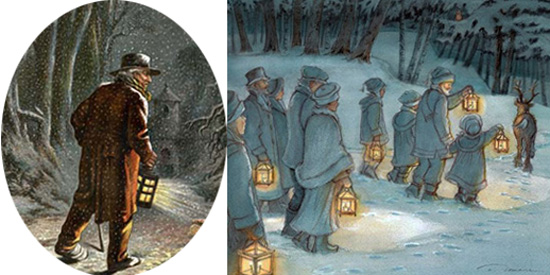

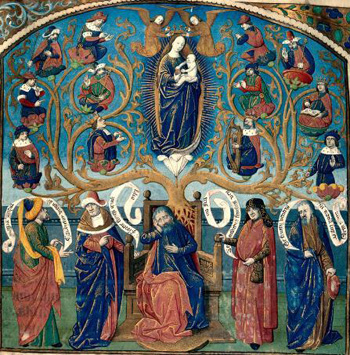

The Catholic peoples of old awoke long before dawn and walked to church on these mornings, carrying their lanterns. The darkness spoke to them of the darkness of the world before Jesus, the Lght of the world, was born and of the need to prepare for the Day of Judgment when Christ would come again.

Village peasants walking in the dark of the night to the Rorate Mass

Because of the intense darkness during this time of the year, many peoples believed that evil spirits roamed more freely – only to be dispelled by signs of the approaching Holiest Night of the Year.

When the English people heard the cock crowing on the dark nights of November or December, they believed that the cock was scaring away the evil spirits to prepare for the coming of the Christ Child. At the sound of the bird, they would exclaim, "The cock is crowing for Christmas!" (Curiosities)

Dark nights reminiscent of the darkness of the world

before Christ

The Poles developed the custom of placing seven candles on the altar with the middle candle raised above the others to symbolize Our Lady. This custom originated in the 1200s by a man of Poznan.

The King admired the custom and introduced it at the Royal Cathedral. During the Rorate Mass, he walked to the altar and lit the highest candle, after which he said aloud, "I am ready for the Judgment Day." He was followed by six other men each representing a different social rank: archbishop, senator, nobleman, soldier, merchant and peasant. (Polish Customs, Traditions, & Folklore, Sophie Hodorowicz Knabpg, p. 23)

This custom illustrates well how every Medieval Catholic – were he king or beggar – was aware that he would have to appear before the Judgment Seat to give an account for his deeds. The Catholic truth and customs created a bond of unity – unheard of in Modern Times – as each Catholic prepared in Advent of the coming of Christ and of the dread Judgment Day.

Baking & preparing for Christmas

Catholic peoples understood that preparing for a great feast required a physical as well as a spiritual cleansing. In every land, housewives cleaned the house thoroughly during the week before Christmas to insure that everything was ready for the great Feast.

Baking & cleaning in preparation for the Christmas Feast

The arrival of the first night of the O Antiphons on December 17 was a signal for housewives from Scandinavia to Greece to begin to bake their traditional Christmas breads, cakes, cookies and pies. Each region had its particular date on which certain Christmas foods should be baked.

English housewives began to bake Mincemeat pies on December 16. Austrian housewives baked the Kletzenbrot (a dried fruit-filled bread) on the Feast of St. Thomas (December 21). One large loaf was made and then smaller loaves made for each member of the family. All of these breads and cakes were placed in safe keeping to be eaten at the Christmas Eve feast and on Christmas morning.

A medieval pig slaughter

In Bavaria, Austria, and Hungary, where it was traditional to eat roast pork on Christmas Day, the men would slaughter the family pig on the Feast of St. Thomas and prepare the "Christmas pig" (Weihnachter) for the feast. Sometimes mischievous young men would attempt to steal the pig's head – or the whole pig – from a neighbor; if the culprit was caught he would be obliged to offer drinks to the whole family as a recompense.

During this Octave before Christmas, monks in medieval monasteries would receive extra treats or gifts each day. At the Saint Benedict Abbey of Fleury (now Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire), the antiphons were recited each day by monks of different rank beginning with the Abbott.

The delicious Kletzenbrot bread

The monk assigned to December 19 might have been the gardener so that he could give a gift from the garden in honor of Our Lord the "Root of Jesse" (O Radix Jesse). The Abbott would always give the gifts on the last day of the O Antiphons (December 23), and his gifts were often very generous.

Medieval expense records show that the foodstuff the Abbott brought to the table on this day of the Expectation were no meager gifts..

Restoring the customs

Today's Catholics should strive to be more medieval in spirit as they prepare for Christmas. The house should be cleaned, silver polished, Christmas breads, cakes and cookies baked and all other necessary preparations made as the great feast draws near.

The O Antiphons would make a fitting addition to the evening prayers of the day, since it is always efficacious to unite with the prayers of the Church. These solemn antiphons used to resound through every church on the evenings preceding Christmas, solemn reminders of the majesty of He who is to come.

If Catholics today were to restore the ancient solemnities and expectation in preparing for the great feast of Christmas in a worthy manner, they could say with the Poles of old, "I, too, am ready for the Judgment Day."

Posted December 16, 2020

______________________

______________________

|

|

|

|

|

|