|

Book Reviews

Benedict XVI: ‘For Many’ Means ‘For All’

Margaret C. Galitzin

Book review of Jesus of Nazareth, by Pope Benedict XVI

San Francisco, Ignatius Press, 2011, volume II, 362 pp.

In the Pope’s Jesus of Nazareth (volume II) he tackles many topics with a “fresh and bold” theology. So the advertisement for the best-seller tells us.

Actually the theology and method are not new for Pope Ratzinger, who for many years has been a proponent of Biblical historicism – a method condemned by St. Pius X. What is this historicism? In a few words, it maintains that Scriptures, and therefore Revelation, are not objective, but need to be read in the context of their time.

Joseph Ratzinger explains it himself in his collaboration on the work Theological Pluralism. He tells us that truth gradually reveals itself in the context of history. “The plenitude of truth does not exist at any point in history,” he states, but man must find it “in the totality of the history of the faith and in his intention to go beyond himself.” (1)

In short, with these “fresh” new readings, truth takes on a relativist character, capable of subtle or not-so-subtle changes as man makes his advance in history.

The formula of the Consecration

In Chapter V of his new work, Benedict examines the formula of Consecration, which he renamed the “words of institution,” spoken over the sacred chalice: “This is my blood of the covenant which is poured out for many (Mark 14:2), to which Matthew adds ‘for many, for the forgiveness of sins’” (26:28).

Progressivists take the words “for many” to mean “for all,” an interpretation which corresponds to their ecumenical aim to say that everybody can be or already is saved by the Blood of Christ. For that reason, up until now the English translation in the Novus Ordo Mass has said “for all,” and not “for many.” Traditionalist Catholics affirm, based on the constant teaching of the Church, that the words mean something different. Here is what the Catechism of the Council of Trent says on the topic:

A relativist interpretation of the Consecration |

"The additional words for you and for many are taken, some from Matthew and some from Luke, but were joined together by the Catholic Church under the guidance of the Spirit of God. They serve to declare the fruit and advantage of His Passion. For if we look to its value, we must confess that the Redeemer shed His Blood for the salvation of all; but if we look to the fruit which mankind has received from it, we shall easily find that it pertains not unto all, but to many of the human race. …

“When, therefore, Our Lord said: For you, He meant either those who were present, or those chosen from among the Jewish people, such as were, with the exception of Judas, the Disciples with whom He was speaking. When He added And for many He wished to be understood to mean the remainder of the elect from among the Jews and Gentiles. With reason, therefore, were the words for all not used, as in this place the fruits of the Passion are alone spoken of, and to the elect only did His Passion bring the fruit of salvation." (2)

This is the clear teaching of the Catholic Church that was universally applied until Vatican II.

Confused language leading to a wrong conclusion

Since Vatican II, a confused language and reasoning has been installed in theology. Benedict’s book follows this style: You can read some paragraphs and wonder what he said. Eventually, once you catch on to some of the progressivist jargon, you begin to think you may understand something. Such muddled theological jargon is also sprinkled through his discussion on the “for many / for all” topic:

What meaning does Benedict give to the Blood of Christ poured out “for many”?

Citing Lutheran theologian Joachim Jeremias, Pope Ratzinger considers that ‘many’ in the Old Testament means ‘the totality,’ and therefore it would be more accurately translated as ‘all.’ On this basis, he affirms, “the word ‘many’ has been translated in a number of languages as ‘all.’”

Instead of referring to tradition or the Church Fathers and Doctors who have addressed this subject, he chooses to present other “prevailing opinions of the day” to show the further “break down” of this supposed new consensus that ‘many’ refers to ‘all.’ To this end he cites the teaching of another Lutheran theologian, Ulrich Wilckens.

Employing the historical method, Benedict must consider “Jesus’ fundamental interpretation of his mission.” According to him, since Christ knew he was to die for mankind his mission took on a universal character. The nascent Church slowly came to understand some of his mission. Gradually she realized Christ died for both Jews and Gentiles. Today, examining his mission “to ransom all,” we continue to grow in understanding as we realize that Christ did indeed die for all. To reinforce this historicist interpretation, he cites another Protestant theologian, Ferdinand Kattenbusch.” (pp 137-138)

In conclusion, while he admits that the “for many” might be a more literal translation of the text, he claims that the more correct understanding of the text is that it applies to “all.”

This is the “bold and fresh” progressivist theology of Benedict XVI. We cannot properly speaking call it Church teaching, since he is not speaking as a Pope but just as a private author.

Quoting the Protestants

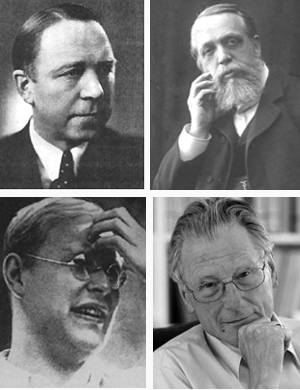

In seven pages Benedict borrows ideas from four Protestants: Jeremias, Kattenbusch, Wilckens and Bonhoeffer (clockwise from top left) |

It is paradoxical, in my view, that Benedict XVI found nothing better to do than quote Protestant theologians to interpret Biblical texts and establish the truth of the Catholic Faith on delicate matters, such as the formula of the Consecration. In fact, he quotes liberally from Protestant scholars throughout volumes 1 and 2 of Jesus of Nazareth.

Just in the seven pages where he comments on the "for many" in the formula of the Consecration, he quoted four Protestants theologians: Ferdinand Kattenbusch and Lutherans Joachim Jeremias, Ulrich Wilckens and Dietrick Bonhoeffer (131-137). The latter, a particular favorite of Benedict, was an early proponent of ecumenism and ended by musing about a “religionless Church.” The few Catholic sources he references are progressivist.

In summary, the only clear conclusions I can reach are that his thinking:

- is confused and tortuous;

- presupposes historical interpretation of the Scriptures;

- presupposes an evolution in dogma;

- is based on Protestant sources;

- is much different from the doctrine of the Council of Trent.

1. Apud Atila Guimaraes, Will He Find Faith, pp. 167-169

2. Council of Trent, “On the Form of the Eucharist”

Posted April 13, 2011

Related Topics of Interest

Card. Ratzinger: I Did Not Change Card. Ratzinger: I Did Not Change

Card. de Lubac: Ratzinger Destroyed the Holy Office Card. de Lubac: Ratzinger Destroyed the Holy Office

Fr. Ratzinger Was under Suspicion of Heresy Fr. Ratzinger Was under Suspicion of Heresy

Card. Ratzinger: Gaudium et Spes Is a 'Counter-Syllabus' Card. Ratzinger: Gaudium et Spes Is a 'Counter-Syllabus'

Card. Ratzinger: No Difference between My Teaching Then and Now Card. Ratzinger: No Difference between My Teaching Then and Now

Desecration of the Holy Eucharist by Adopting Large Hosts Desecration of the Holy Eucharist by Adopting Large Hosts

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Book Reviews | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|