|

Socio-Political Issues

Liberalism, Socialism, Feudalism - V

Subsidiarity & Feudalism

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Did the principle of subsidiarity that we studied in the last article have an application in the Middle Ages? It had an application in the Feudalism. Medieval Feudalism was precisely this.

The Saracens represented a serious danger for all of Europe that imposed defensive measures

|

You can understand this by studying the origin of the fief, or feodum. Imagine the cultivated lands and their owners at the time of Charlemagne in the 8th century. The Viking invasions were a clear risk hovering over the Empire. They became a reality soon after Charlemagne died in 814. Also the Saracens in Spain and North Africa were threatening the frontiers of the Empire. Given the bad roads, communications were quite difficult through the various parts of the Empire. The result was that the workers had a natural tendency to group around the larger, better protected and wealthier household, and try to live inside its borders. Inside its wall, they would fight against any invader when it became necessary.

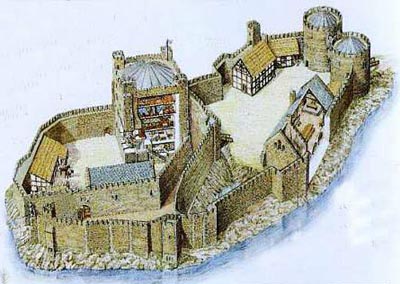

It happens that this better protected house was that of their employer or the most prosperous farmer in the area, and this house increasingly became more strongly fortified. First, that better-off farmer built wood towers along the borders of his property and a strong fence around it. As the dangers became more frequent, those wood towers and fence were transformed into stone walls and high towers so that the enemy could be seen from afar. When the sentinel would see the danger approaching, he would ring a bell or blow a horn to warn the families in the surrounding area and call all available men to take arms and meet in the courtyard.

In that household, which became a fortress, the resistance against the enemy would be organized. As necessity required, around those towers and walls a deep trench filled with water was added so that the enemy could not scale its walls with ladders. Such defenses were built for the common protection of both the head farmer, the smaller farmers and the workers to protect them from death, imprisonment, torture or enslavement by the Vikings or Saracens. The castle was born, therefore, from the common need for protection.

The castle, built to defend nobles and workers, became the symbol of subsidiarity in Feudalism |

Since an authority was needed to direct the castle and the fight against the adversary, the natural choice fell to its owner. He had the most at stake to lose; therefore, he would be the most intrepid. He and his family were the ones who were normally on the front lines of the counter-attack. Thus, the family of the farmer was naturally transformed into a family of warriors.

In times of war, then, the owner led the battle; in times of peace, he would also direct his castle and its environs. Slowly the function of mayor of that territory fell to him, as well as that of judge and police chief. So, what was the feudal lord? He was a famer who, for the good of his subordinates, assumed the functions of mayor, judge and police chief in the area where he lived.

But as those invasions increased, so also did the danger for those heads of castles. So, it became convenient to establish relations of defense among the various owners of castles. Agreements were established that stipulated when one castle was attacked, the other lords would come to its aid with their troops to help defend it. Consequently, in each castle, underground tunnels were dug leading to some secret spot in the nearby forest or hills so that, should the castle be surrounded by enemies, a messenger could secretly exit it to notify the others lords to come to its aid.

It was necessity that led to these accords. Obviously each lord would try to contract the help of a neighboring lord who had more troops. Since, in the inverse case, the smaller lord could not bring the same number of troops to the greater lord to assist him, the weaker would offer his services to the stronger in compensation. This is how a natural hierarchy among those lords was born. By an analogous system of protection and services, the King was above all those feudal lords.

What is the principle that ruled the feudal system? One feudal lord would protect and care for his own territory as much as he could. He would only have recourse to his superior in cases where he absolutely needed the assistance. This practice applied through the whole hierarchy until it reached the top, the King. One can see that Feudalism was, in fact, none other than the application of the principle of subsidiarity.

The feudal order was not a planned thing. At its base there was no sociologist who sat at a table and invented Feudalism. This was not what happened. Feudalism was born naturally from the need of the people facing those invasions and from the application of the principle of subsidiarity to that need.

The same principle in the cities

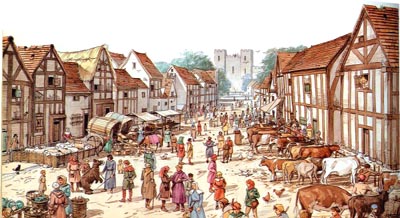

In other places, the need did not arise from agricultural conditions, but from an urban setting. The cities were fortified for similar reasons. But the workers did not gather around a natural employer or a stronger family. Instead, since the people of the city elected their own authorities, when a danger was present, they would rely on them for protection.

Although there were elected authorities in the cities, subsidiarity was also a characterisitic of urban life |

This gave birth to the medieval city, which had an elective organization that was neither monarchic nor hereditary. Such elective system became so rich that it was common in some cities to have different mayors for the different districts, as in the case of Brussels, for example.

This was another way to apply the principle of subsidiarity. Following the same principle, the higher government of the city would only intervene in those districts in matters that the lower authority could not resolve.

Paradoxically, in this system, both in the cities and the countryside, the one with the more limited sphere of action was not the worker, which is what the Revolution spreads, but the King.

How work was organized

Now, how was work organized in the Middle Ages?

The desire for autonomy was so strong that institutions were born within the cities operating as if they were small cities.

For example, a university would be established and come to occupy a good part of a district – or even all of it because some universities were colossal. Then, it would fall to the Rector of the university to assume the functions of mayor, judge, police chief, etc. of his small city. He would be the authority over that place. In case of a complaint against him, the mayor of the city would intervene; should he appeal the decision of the city authority, the Lord of the area or the King – depending on the case – would be the one to judge it.

Here in São Paulo we have a remnant of this system in the Faculty of Law in San Francisco Square, where the city police cannot enter. This remotely comes from medieval privileges granted to the Portuguese universities that established the Rector as the only one to exercise the role of police chief in it. So, we have this curious contradiction: The very Faculty where professors and students speak against Feudalism has its own territory free from city governance as a right inherited from Feudalism.

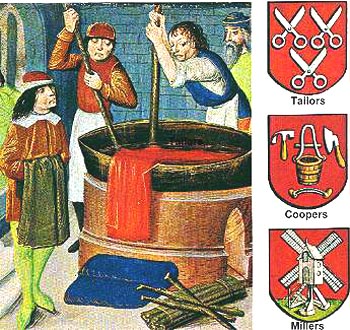

This structure of subsidiarity was also applied to trades and work. In the Middle Ages the man was valued much more than the machine. This was for noble reasons, we know, but also because technology relied less on machines, which were smaller and more primitive. The machines were often made of wood and, therefore, more accessible and cheaper to buy. So, the worker was much more valuable than the machine. For this reason, the capitalist as we know him today – who has capital and builds a factory – did not exist. The owner of a workshop could found his with incomparably less money.

Each guild had autonomy; the city would only intervene in matters the guild could not resolve |

The trade workers were artisans who entered their professions as apprentices. Their own talents - rather than machines - were what determined production because almost everything was handmade. Those who were more skilled would become companions, and then masters. The master, after due tests supervized by the guild, would be allowed to have his own workshop.

This workshop was habitually small, occupying one or two rooms of the same building where the owner lived. The workers worked under his close supervision and, at meals, would eat together with him. It constituted a kind of family that relied on the master, who had a preeminence based on his superior practice and knowledge of the common work. This kind of workshop would have 10, 15 or, at the most, 20 workers.

In a spontaneous movement, workshops of the same trade or profession would group together on the same street or in the same bloc. If someone wanted a jewel, for instance, he would go the street of the goldsmiths, or if he needed to buy a pair of shoes, he could go to the street of the shoemakers, and so on.

Thus, in the street of the shoemakers where there were many workshops of this trade, that area would be directed by the officers of the shoemakers’ guild, and not by the city authorities. Again, here we can see the application of the principle of subsidiarity. As soon as a trade or work group would become organized, it would claim its autonomy and right to govern itself.

In the Middle Ages, a large hospital such as the Holy House of Mercy would have as much autonomy regarding its internal affairs as a small municipality: it would have its own laws, its own authorities, its own judge with its own police and its own jail. This was the medieval organization.

In the next article we will see the repercussion this system had in every aspect of medieval life.

Continued

Posted May 14, 2012

Related Topics of Interest

The Principle of Subsidiarity The Principle of Subsidiarity

Discussing Liberal & Socialist Democracies Discussing Liberal & Socialist Democracies

Socialism Exploits Liberalism’s Flaws Socialism Exploits Liberalism’s Flaws

The Fiasco of Socialism & Basics on Catholic Authority The Fiasco of Socialism & Basics on Catholic Authority

Feudalism and the Modern State Feudalism and the Modern State

The Organic Formation of Feudalism The Organic Formation of Feudalism

Proportion between the City and the Man Proportion between the City and the Man

Groups of Friends and Guilds Groups of Friends and Guilds

The Organic Formation of a Region The Organic Formation of a Region

Related Works of Interest

|

|

Social-Political | Hot Topics | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights

Reserved

|

|

|