Art & Architecture

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jesus on the Cross by Chagall

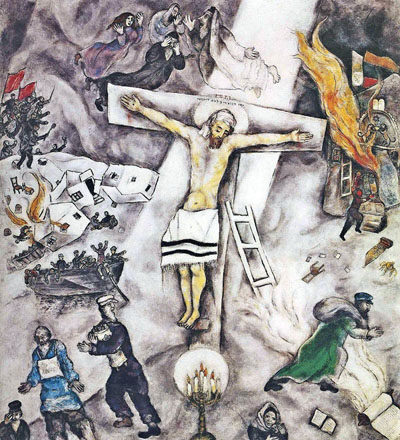

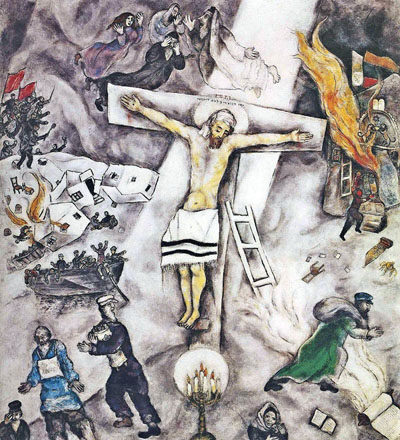

Marc Chagall is the preferred artist of Jorge Bergoglio – now Pope Francis I – and his favorite painting is the White Crucifixion. I find both facts significant.

Chagall was definitely an early adherent of the modernist school of painting. A Russian artist who lived from 1887 to 1985, he experimented with cubism, symbolism and fauvism and even dabbled in surrealism before settling on an expressionism toned by Jewish mysticism.

Chagall was definitely an early adherent of the modernist school of painting. A Russian artist who lived from 1887 to 1985, he experimented with cubism, symbolism and fauvism and even dabbled in surrealism before settling on an expressionism toned by Jewish mysticism.

Before Vatican II, the Church condemned these schools of modern art, warning the faithful of their revolutionary,occult and oftensatanic roots. After Paul VI adopted his contorted crucifix by Scorzelli in 1963 and inaugurated a collection of modern art at the Vatican, it became common to find expressionist works like Chagall’s decorating the modern churches and illustrating the covers of missalettes.

By his choice of favorite artist, Francis sends the message he has no plans to change the direction of modern art in the Conciliar Church… Another piece of bad news for traditionalists.

Perhaps more disturbing is Pope Bergoglio’s choice of favorite painting: the White Crucifixion which hangs on the third floor of the modern wing of Chicago’s Art Institute. Like many of Chagall’s works, it is busy and crowded, leaving the viewer confused at first glance. But it is worth a second glance to understand Chagall’s message endorsed by Francis.

Christ symbolizes the suffering of the Jews

Chagall painted the White Crucifixion after the breakout of the Nazi pogroms against the Jews in November 1938, on the eve of World War II.

Christ crucified is in the center, but Chagall himself said later, it is by no means a ‘Christian’ picture. The scenes that surround the Cross - a shattered village, a pillaged burning synagogue – tell its real meaning. It is a Christ who symbolizes the Jews who suffered at the hands of the Nazis.

Christ crucified is in the center, but Chagall himself said later, it is by no means a ‘Christian’ picture. The scenes that surround the Cross - a shattered village, a pillaged burning synagogue – tell its real meaning. It is a Christ who symbolizes the Jews who suffered at the hands of the Nazis.

If we look more closely at this mirage of scenes, we see on the upper left there is a horrified woman and three rabbis fleeing; a little below them to the left soldiers carrying red banners press forward killing villagers and destroying their houses and obliging others to flee across the water in a boat.

Now, let us go to the top right where we see a synagogue being burned by a Nazi brownshirt with Nazi flags flying above the flames. The synagogue’s furniture and books are thrown out into the street.

Below, on both sides of the Cross, we see people running from those persecutions to hide and save the Jewish religious books and symbols from desecration. Among these fleeing people, there is one in blue at left who wears a placard, which said ‘Ich bin Jude’ (‘I am a Jew’). (1)

At right below the Cross a white light comes from a scroll of the Torah and moves up a ladder to the Cross. The light is traversed by a green clad figure carrying a bundle. This figure appears in a number of Chagall’s painting and has been interpreted as the wanderer Jewish of Yiddish tradition.

Dominating the picture in the center is the figure of Christ crucified. But this is very much a Jewish Christ who wears a Jewish tallith instead of a loincloth. His head is covered by a bandana. Over his head written in Hebrew and Latin are the words 'King of the Jews.’ Below, at his feet burns a menorah - strangely, with only six candles, one unlit – which is surrounded by a halo like the one that frames his head.

According to Chagall’s White Crucifixion, Christ’s suffering and death had nothing to do with the Redemption of the human race and man’s salvation. This Jewish Christ is suffering and perhaps holy, but he is not divine.

Thus, the figure of Jesus on the Cross sums up the suffering of the Jewish people. Chagall himself affirmed this decades after the war, “For me, Christ always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr.” (2) We have, therefore, a syncretism of the two religions in which Judaism maintains the upper hand.

This is why Chagall painted a crucified Christ in a number of his paintings. This is also why even before Vatican II, Jewish reaction to Chagall's crucifixion scenes was positive. It was accepted by revolutionary circles everywhere. They understood Chagall’s Jewish loyalties were hardly compromised by his choice of the crucifixion motif. Jacques Maritain called it “beautiful,” “Israelis climbing Calvary.”

Bergoglio also finds it beautiful. He is clearly comfortable with Chagall’s message that Christ symbolizes the Jewish people and not redemption. It fits with Francis' constant preaching favoring the poor, the oppressed and the marginalized. And, as a progressivist and avid promoter of the declaration Nostra aetate, he is sympathetic to Chagall’s syncretist interpretation of the crucifixion.

Chagall's occult expressionalist work Paradise

Before Vatican II, the Church condemned these schools of modern art, warning the faithful of their revolutionary,occult and oftensatanic roots. After Paul VI adopted his contorted crucifix by Scorzelli in 1963 and inaugurated a collection of modern art at the Vatican, it became common to find expressionist works like Chagall’s decorating the modern churches and illustrating the covers of missalettes.

By his choice of favorite artist, Francis sends the message he has no plans to change the direction of modern art in the Conciliar Church… Another piece of bad news for traditionalists.

Perhaps more disturbing is Pope Bergoglio’s choice of favorite painting: the White Crucifixion which hangs on the third floor of the modern wing of Chicago’s Art Institute. Like many of Chagall’s works, it is busy and crowded, leaving the viewer confused at first glance. But it is worth a second glance to understand Chagall’s message endorsed by Francis.

Christ symbolizes the suffering of the Jews

Chagall painted the White Crucifixion after the breakout of the Nazi pogroms against the Jews in November 1938, on the eve of World War II.

Chagall's White Crucifixion

If we look more closely at this mirage of scenes, we see on the upper left there is a horrified woman and three rabbis fleeing; a little below them to the left soldiers carrying red banners press forward killing villagers and destroying their houses and obliging others to flee across the water in a boat.

Now, let us go to the top right where we see a synagogue being burned by a Nazi brownshirt with Nazi flags flying above the flames. The synagogue’s furniture and books are thrown out into the street.

Below, on both sides of the Cross, we see people running from those persecutions to hide and save the Jewish religious books and symbols from desecration. Among these fleeing people, there is one in blue at left who wears a placard, which said ‘Ich bin Jude’ (‘I am a Jew’). (1)

At right below the Cross a white light comes from a scroll of the Torah and moves up a ladder to the Cross. The light is traversed by a green clad figure carrying a bundle. This figure appears in a number of Chagall’s painting and has been interpreted as the wanderer Jewish of Yiddish tradition.

Dominating the picture in the center is the figure of Christ crucified. But this is very much a Jewish Christ who wears a Jewish tallith instead of a loincloth. His head is covered by a bandana. Over his head written in Hebrew and Latin are the words 'King of the Jews.’ Below, at his feet burns a menorah - strangely, with only six candles, one unlit – which is surrounded by a halo like the one that frames his head.

According to Chagall’s White Crucifixion, Christ’s suffering and death had nothing to do with the Redemption of the human race and man’s salvation. This Jewish Christ is suffering and perhaps holy, but he is not divine.

Thus, the figure of Jesus on the Cross sums up the suffering of the Jewish people. Chagall himself affirmed this decades after the war, “For me, Christ always symbolized the true type of the Jewish martyr.” (2) We have, therefore, a syncretism of the two religions in which Judaism maintains the upper hand.

This is why Chagall painted a crucified Christ in a number of his paintings. This is also why even before Vatican II, Jewish reaction to Chagall's crucifixion scenes was positive. It was accepted by revolutionary circles everywhere. They understood Chagall’s Jewish loyalties were hardly compromised by his choice of the crucifixion motif. Jacques Maritain called it “beautiful,” “Israelis climbing Calvary.”

Bergoglio also finds it beautiful. He is clearly comfortable with Chagall’s message that Christ symbolizes the Jewish people and not redemption. It fits with Francis' constant preaching favoring the poor, the oppressed and the marginalized. And, as a progressivist and avid promoter of the declaration Nostra aetate, he is sympathetic to Chagall’s syncretist interpretation of the crucifixion.

- Jeremy Cohen, Christ Killers: the Jews and the Passion, NY: Oxford Un. Press, 2007, p. 164-165

- Ibid., p. 166

Posted July 8, 2013

______________________

______________________