Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lacunae & Objectivity in

Moses and Monotheism

In my previous articles I tried to sketch a profile of the life and work of Sigmund Freud and his most important disciple, Karl Jung.

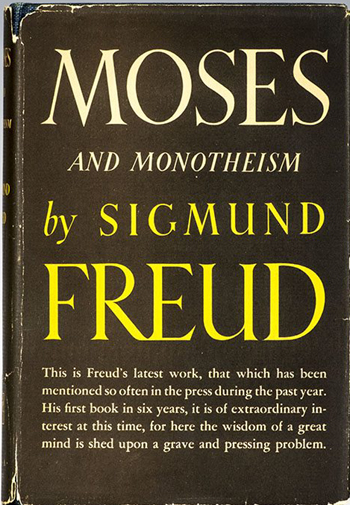

Now, I will address Freud’s last work – Moses and Monotheism – finished in 1939, weeks before his flight to London to escape the Nazi persecution after the annexation of Austria – the Anschluss – by Hitler’s Germany.

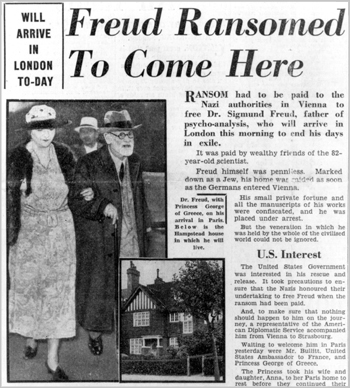

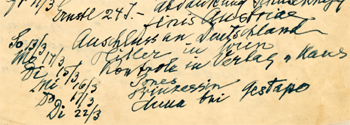

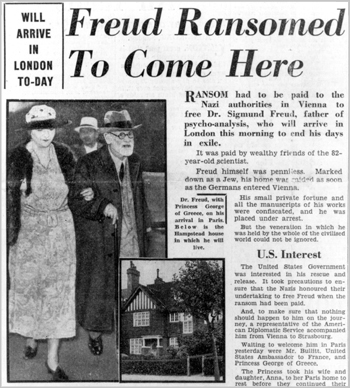

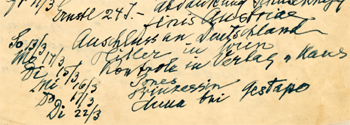

The Gestapo had been harassing Freud for several months, and on March 12, 1938, he was arrested. After negotiations made by the American ambassador in Vienna and the action of influential friends, such as Ernest Jones and Princess Marie Bonaparte, Freud left his native Vienna for London on June 4 of that same year. On that day he wrote in his personal diary: “Finis Austriae.”

The Gestapo had been harassing Freud for several months, and on March 12, 1938, he was arrested. After negotiations made by the American ambassador in Vienna and the action of influential friends, such as Ernest Jones and Princess Marie Bonaparte, Freud left his native Vienna for London on June 4 of that same year. On that day he wrote in his personal diary: “Finis Austriae.”

In passing I note that four sisters of Freud died in Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

Although sad about leaving Austria, he was familiar with England from his youth and liked it. In a letter to his brother Alexander he wrote: “England … – in spite of everything that strikes one as foreign, peculiar and difficult, and of this there is quite enough – is a blessed, a happy country inhabited by well-meaning, hospitable people.”

Moses and Monotheism, which Freud brought in his suitcase to London, was first published in in 1939 in German and shortly afterwards in English the same year. After the defeat of Hitler the work was also published in Germany in his Gesammelte Werke – Complete Works.

Moses and Monotheism raised irritation among many people, principally some Jewish rabbis who wanted to “excommunicate” Freud, which in fact never happened. The reason for their fury: At the beginning of his work, the author affirmed that “Moses was probably not Hebrew but Egyptian.”

Further, he also stated that Moses’ idea of establishing a new religion with one sole God, monotheism, was nothing more than the return to the short-lived cult to the god Aten, established by Pharaoh Akhenaten, or Amenhotep IV (1353 –1336 BC), long before Moses’ birth. Indeed, this Pharaoh, “the world’s earliest recorded monotheist,” had declared that Aten was the one and only god. After the death of this Pharaoh, Egypt returned to its ancient pantheism.

So, in Freud’s view, Moses – whom he considered to be Egyptian – had revived the religious concept of one single God with the intent to establish the Reign of Law over the reign of the senses, the latter always being confusing and arbitrary.

This is one of the central points of his work: What the great Jewish leader did was to establish the Law, therefore, the start of civilization, to tame the barbarianism of the senses, man’s desires and the human and sexual relationships that were still quite disorderly in the Eastern world. This is the central idea for the development of organized peoples.

I insist upon the fact that that nowhere in his work did Freud allude to the true God who revealed himself to Moses, chose a people and gave them the mission of bringing the true God to all mankind.

I insist upon the fact that that nowhere in his work did Freud allude to the true God who revealed himself to Moses, chose a people and gave them the mission of bringing the true God to all mankind.

The author had the evolutionist idea of a civilizing process through which the many gods of polytheism, with their caprices, fights, contradictory wishes and emotions, gradually evolved to only one god, who organized mankind with his laws and rules that must be followed to build a people and a nation.

Thus, according to Freud, mankind left the “world of passions” (polytheism) and entered the “world of law” (monotheism). In this way mankind abandoned the “matriarchal structure of the emotions” to enter the “patriarchal structure” of law, organization and civility.

Following the same line of thoughts set out in his previous work Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud continued to describe what he called the “great modern tragedy,” which is the return to the “matriarchal structure” of the “lawless world of the passions,” as a clear reference to Nazism and its anti-civilizing fury. He did not include Socialism and Communism in his criticism, although he could have.

At any rate, his book was attacked by the Nazis as “Semitic propaganda” and by the Marxists as rightist and reactionary. For example, Georg Lukács, a well-known Hungarian Marxist intellectual (1885-1971), made strong attacks against all the works of Freud, and particularly this book. Lukács was already criticizing Freud in 1922 in an essay titled The Psychology of the Masses in Freud, first published in Germany under the Weimar Republic. Lukács’ continued to oppose Freud’s work for many years.

As I mentioned, Moses and Monotheism was also criticized by Jewish rabbis.

It seems to me that Freud’s theory of the passage of the world from his the “matriarchal” stage, which was the reign of the passions, to the “patriarchal” one, the empire of law, was a sound observation and something good. To confirm this, we can see how the opposite is something bad: The impressive decline in civilization we are experiencing today in which the gender ideology, the legalization of abortion and sexual liberalization represent the return to the reign of the passions, which is causing an enormous moral harm to humanity.

It is unfortunate that, in the change from the “matriarchal structure” to the “patriarchal structure,” Freud did not see anything but evolutionary stages without a transcendent moral meaning.

As Catholics we would say that what happened with Moses was the passage of the world of the passions to the world of law, which prepared for the world of grace, which came with the Redemption achieved by Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Continued

Now, I will address Freud’s last work – Moses and Monotheism – finished in 1939, weeks before his flight to London to escape the Nazi persecution after the annexation of Austria – the Anschluss – by Hitler’s Germany.

Freud wrote ‘Finis Austriae’ in his diary (below)

before he fled Austria for England (above)

In passing I note that four sisters of Freud died in Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

Although sad about leaving Austria, he was familiar with England from his youth and liked it. In a letter to his brother Alexander he wrote: “England … – in spite of everything that strikes one as foreign, peculiar and difficult, and of this there is quite enough – is a blessed, a happy country inhabited by well-meaning, hospitable people.”

Moses and Monotheism, which Freud brought in his suitcase to London, was first published in in 1939 in German and shortly afterwards in English the same year. After the defeat of Hitler the work was also published in Germany in his Gesammelte Werke – Complete Works.

Moses and Monotheism raised irritation among many people, principally some Jewish rabbis who wanted to “excommunicate” Freud, which in fact never happened. The reason for their fury: At the beginning of his work, the author affirmed that “Moses was probably not Hebrew but Egyptian.”

Further, he also stated that Moses’ idea of establishing a new religion with one sole God, monotheism, was nothing more than the return to the short-lived cult to the god Aten, established by Pharaoh Akhenaten, or Amenhotep IV (1353 –1336 BC), long before Moses’ birth. Indeed, this Pharaoh, “the world’s earliest recorded monotheist,” had declared that Aten was the one and only god. After the death of this Pharaoh, Egypt returned to its ancient pantheism.

So, in Freud’s view, Moses – whom he considered to be Egyptian – had revived the religious concept of one single God with the intent to establish the Reign of Law over the reign of the senses, the latter always being confusing and arbitrary.

This is one of the central points of his work: What the great Jewish leader did was to establish the Law, therefore, the start of civilization, to tame the barbarianism of the senses, man’s desires and the human and sexual relationships that were still quite disorderly in the Eastern world. This is the central idea for the development of organized peoples.

Freud chose not to criticize Socialism or Communism

The author had the evolutionist idea of a civilizing process through which the many gods of polytheism, with their caprices, fights, contradictory wishes and emotions, gradually evolved to only one god, who organized mankind with his laws and rules that must be followed to build a people and a nation.

Thus, according to Freud, mankind left the “world of passions” (polytheism) and entered the “world of law” (monotheism). In this way mankind abandoned the “matriarchal structure of the emotions” to enter the “patriarchal structure” of law, organization and civility.

Following the same line of thoughts set out in his previous work Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud continued to describe what he called the “great modern tragedy,” which is the return to the “matriarchal structure” of the “lawless world of the passions,” as a clear reference to Nazism and its anti-civilizing fury. He did not include Socialism and Communism in his criticism, although he could have.

At any rate, his book was attacked by the Nazis as “Semitic propaganda” and by the Marxists as rightist and reactionary. For example, Georg Lukács, a well-known Hungarian Marxist intellectual (1885-1971), made strong attacks against all the works of Freud, and particularly this book. Lukács was already criticizing Freud in 1922 in an essay titled The Psychology of the Masses in Freud, first published in Germany under the Weimar Republic. Lukács’ continued to oppose Freud’s work for many years.

As I mentioned, Moses and Monotheism was also criticized by Jewish rabbis.

It seems to me that Freud’s theory of the passage of the world from his the “matriarchal” stage, which was the reign of the passions, to the “patriarchal” one, the empire of law, was a sound observation and something good. To confirm this, we can see how the opposite is something bad: The impressive decline in civilization we are experiencing today in which the gender ideology, the legalization of abortion and sexual liberalization represent the return to the reign of the passions, which is causing an enormous moral harm to humanity.

It is unfortunate that, in the change from the “matriarchal structure” to the “patriarchal structure,” Freud did not see anything but evolutionary stages without a transcendent moral meaning.

As Catholics we would say that what happened with Moses was the passage of the world of the passions to the world of law, which prepared for the world of grace, which came with the Redemption achieved by Our Lord Jesus Christ.

Continued

Posted May 19, 2021

______________________

______________________