Personalities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dom Vital – II

Prison & Condemnation by

the Imperial Government

After the Recife newspapers published the list of priests who belonged to Freemasonry (see the last article), Dom Vital summoned those priests to a meeting and inquired of each one if the accusation was true. He, then, asked those who confirmed their membership to abjure.

Some refused, and Dom Vital begged them on his knees, for the love of priestly dignity, to abandon Freemasonry and renounce it. Many of them did not. Since he was unable to set them on the good path, he arose and, with great majesty, declared: “In these conditions, I must excommunicate you.”

He took the same procedure with the religious brotherhoods. He asked the Masonic leaders of the religious brotherhoods to renounce Freemasonry. When they did not comply, he excommunicated them and issued a series of decrees blasting Freemasonry.

We see what a colossal Pastor he was: He employed all the means dictated by prudence, he had all the charity and meekness possible, but when they did not produce the required effect, armed with due evidence he did not hesitate to initiate, like a lion, the great combat of his life.

These measures caused great turmoil in the Masonic Empire of Brazil. The point of contention was that Dom Vital based his actions on the pontifical documents of Pius IX and the imperial government maintained that those documents were not applicable in Brazil until the Emperor had officially approved them.

These measures caused great turmoil in the Masonic Empire of Brazil. The point of contention was that Dom Vital based his actions on the pontifical documents of Pius IX and the imperial government maintained that those documents were not applicable in Brazil until the Emperor had officially approved them.

This thesis was theologically incorrect since, if the Pope were to require the license of emperors or presidents of republics for his acts to enter into effect, he would not have direct and universal jurisdiction over the faithful. Then, the unity of the Church would be broken.

Dom Vital exchanged correspondence with the imperial government defending the Church as well as his right to attack Freemasonry, but that exchange ended with his arrest. An imperial order was issued to imprison him and take him from Recife to Rio de Janeiro to be judged by an imperial tribunal.

Dom Vital received that order in a famous scene that I have the pleasure to relate here. A judge, a police officer and an army colonel were designated to deliver the order of arrest. Dom Vital was aware that he would be arrested and awaited the officers dressed in the solemn apparel of a Bishop accompanied by his clergy.

The officers entered the Episcopal Palace and Dom Vital appeared before them with miter and crosier.

The police officer said: “Your Excellency, I have the duty to arrest you.”

Dom Vital replied: “Well, here I am.”

The officer: “Your Excellency must consider yourself under arrest.”

Dom Vital: “Not until you have set your hand on me so that I have proof that you made violence against my will.”

The officer approached him, placed his blasphemous hand on the Bishop’s shoulder, and said: “Your Excellency is under arrest.”

Dom Vital: “Since I have suffered violence from the part of the State, I will accompany you, but I will go on foot.”

I do not remember the distance between the Palace of the Soledad and the port where the ship was awaiting him, but he knew that, if he were walking, he would certainly be followed by a part of the population. People would inevitably spread the news: “The Empire is arresting the Bishop.”

I do not remember the distance between the Palace of the Soledad and the port where the ship was awaiting him, but he knew that, if he were walking, he would certainly be followed by a part of the population. People would inevitably spread the news: “The Empire is arresting the Bishop.”

This would produce snowball reactions that would greatly harm the prestige of the Empire. If such an action could not occur in Brazil today without raising great social-political turmoil, we can imagine how much more vivid the reaction would be at that time. Thus, fearing the people would rally to support Dom Vital and the government would become more unpopular, the civil authorities forbade the Prelate to go by foot.

Something similar happened on his way to Rio. The authorities changed him from the first ship to another in Salvador to prevent the population from receiving Dom Vital with a warm welcome in Rio. Instead, he entered secretly and was transferred directly to a Navy prison where he remained until the day of the trial.

He entered the courtroom and was conducted to a small undignified bench designated for him. One of the jurists, who was favorable to Dom Vital, picked up his own chair and brought it to the Bishop so that he might be honorably seated.

Two famous lawyers were chosen to defend him: Zacarias de Gois, a senator and renowned statesman, and Cândido Mendes de Almeida. Before the defense started, Dom Vital made this statement before the tribunal : “I refuse the defense that has been offered to me because I deny the right of this civil tribunal to judge a Bishop of the Roman, Catholic and Apostolic Church. A Bishop can only be judged by the Pope. Therefore, I declare my opposition to this defense.”

On the defendant bench were two other Bishops who chose to accompany Dom Vital in this unjust trial: the Bishop of Rio, Dom Pedro Maria de Lacerda, a man without value, and an American Bishop who happened to be in Rio and wanted to sit with him. The galleries of the tribunal were filled with people who enthusiastically applauded the Prelate.

He was condemned to four years of imprisonment with hard labor. The Emperor dispensed him from the labor because he feared that the government could fall in face of the indignation of the people. His companion in prison was Dom Macedo Costa, a pre-progressivist, a spineless middle-of- the-road Bishop who was always seeking compromise and compliance. I believe that having him as a companion in prison was one of Dom Vital’s greatest sufferings.

In prison he suffered enormous pressure to lift the excommunications he had issued in Recife. If he had agreed, he would have been released. But Dom Vital was always inflexible and refused.

In prison he suffered enormous pressure to lift the excommunications he had issued in Recife. If he had agreed, he would have been released. But Dom Vital was always inflexible and refused.

He started all the letters he wrote from prison with these words: “From my prison on the Ilha das Cobras (Island of the Serpents),” followed by the date. In this way he documented the time he remained in prison.

During Dom Vital’s imprisonment, his popularity swelled like a great wave over all Brazil and the fortress became a site of pilgrimage. Following the fashion of Liberalism of the time, the government permitted a special service to conduct persons who wanted to visit him at the Ilha das Cobras. From the mountains of Minas Gerais, for example, entire families including the women and children would come on horseback to visit Dom Vital and ask for his blessing. It was a constant pilgrimage. I am reporting here just a few episodes that my bad memory has retained.

Dom Vital received all these people with goodness.

Continued

Some refused, and Dom Vital begged them on his knees, for the love of priestly dignity, to abandon Freemasonry and renounce it. Many of them did not. Since he was unable to set them on the good path, he arose and, with great majesty, declared: “In these conditions, I must excommunicate you.”

He took the same procedure with the religious brotherhoods. He asked the Masonic leaders of the religious brotherhoods to renounce Freemasonry. When they did not comply, he excommunicated them and issued a series of decrees blasting Freemasonry.

We see what a colossal Pastor he was: He employed all the means dictated by prudence, he had all the charity and meekness possible, but when they did not produce the required effect, armed with due evidence he did not hesitate to initiate, like a lion, the great combat of his life.

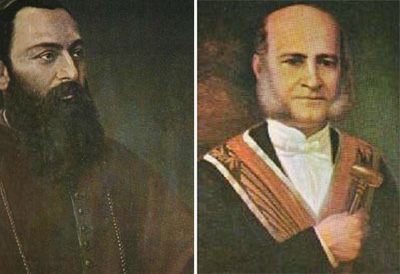

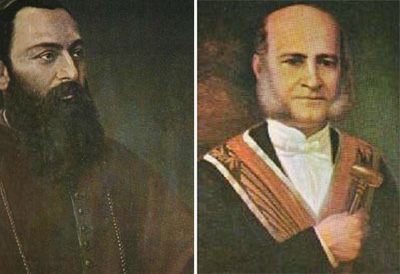

The two poles of the dispute: Dom Vital, left, and Baron of Rio Branco, Prime Minister & Grand Master of Freemasonry

This thesis was theologically incorrect since, if the Pope were to require the license of emperors or presidents of republics for his acts to enter into effect, he would not have direct and universal jurisdiction over the faithful. Then, the unity of the Church would be broken.

Dom Vital exchanged correspondence with the imperial government defending the Church as well as his right to attack Freemasonry, but that exchange ended with his arrest. An imperial order was issued to imprison him and take him from Recife to Rio de Janeiro to be judged by an imperial tribunal.

Dom Vital received that order in a famous scene that I have the pleasure to relate here. A judge, a police officer and an army colonel were designated to deliver the order of arrest. Dom Vital was aware that he would be arrested and awaited the officers dressed in the solemn apparel of a Bishop accompanied by his clergy.

The officers entered the Episcopal Palace and Dom Vital appeared before them with miter and crosier.

The police officer said: “Your Excellency, I have the duty to arrest you.”

Dom Vital replied: “Well, here I am.”

The officer: “Your Excellency must consider yourself under arrest.”

Dom Vital: “Not until you have set your hand on me so that I have proof that you made violence against my will.”

The officer approached him, placed his blasphemous hand on the Bishop’s shoulder, and said: “Your Excellency is under arrest.”

Dom Vital: “Since I have suffered violence from the part of the State, I will accompany you, but I will go on foot.”

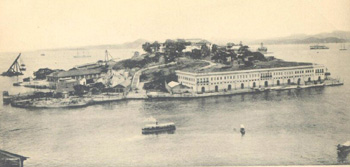

Dom Vital had two co-cathedrals, one for Olinda, top, & another for Recife, a sister city turned toward business

This would produce snowball reactions that would greatly harm the prestige of the Empire. If such an action could not occur in Brazil today without raising great social-political turmoil, we can imagine how much more vivid the reaction would be at that time. Thus, fearing the people would rally to support Dom Vital and the government would become more unpopular, the civil authorities forbade the Prelate to go by foot.

Something similar happened on his way to Rio. The authorities changed him from the first ship to another in Salvador to prevent the population from receiving Dom Vital with a warm welcome in Rio. Instead, he entered secretly and was transferred directly to a Navy prison where he remained until the day of the trial.

He entered the courtroom and was conducted to a small undignified bench designated for him. One of the jurists, who was favorable to Dom Vital, picked up his own chair and brought it to the Bishop so that he might be honorably seated.

Two famous lawyers were chosen to defend him: Zacarias de Gois, a senator and renowned statesman, and Cândido Mendes de Almeida. Before the defense started, Dom Vital made this statement before the tribunal : “I refuse the defense that has been offered to me because I deny the right of this civil tribunal to judge a Bishop of the Roman, Catholic and Apostolic Church. A Bishop can only be judged by the Pope. Therefore, I declare my opposition to this defense.”

On the defendant bench were two other Bishops who chose to accompany Dom Vital in this unjust trial: the Bishop of Rio, Dom Pedro Maria de Lacerda, a man without value, and an American Bishop who happened to be in Rio and wanted to sit with him. The galleries of the tribunal were filled with people who enthusiastically applauded the Prelate.

He was condemned to four years of imprisonment with hard labor. The Emperor dispensed him from the labor because he feared that the government could fall in face of the indignation of the people. His companion in prison was Dom Macedo Costa, a pre-progressivist, a spineless middle-of- the-road Bishop who was always seeking compromise and compliance. I believe that having him as a companion in prison was one of Dom Vital’s greatest sufferings.

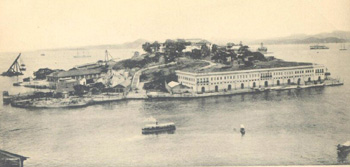

At the top of Ilha das Cobras, above, was a fortress where Dom Vital was maintained prisoner

He started all the letters he wrote from prison with these words: “From my prison on the Ilha das Cobras (Island of the Serpents),” followed by the date. In this way he documented the time he remained in prison.

During Dom Vital’s imprisonment, his popularity swelled like a great wave over all Brazil and the fortress became a site of pilgrimage. Following the fashion of Liberalism of the time, the government permitted a special service to conduct persons who wanted to visit him at the Ilha das Cobras. From the mountains of Minas Gerais, for example, entire families including the women and children would come on horseback to visit Dom Vital and ask for his blessing. It was a constant pilgrimage. I am reporting here just a few episodes that my bad memory has retained.

Dom Vital received all these people with goodness.

Continued

Posted July 6, 2015

______________________

______________________