|

American History

Protestant Terrorism against Catholicism - Part I

The Burning of the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D.

In his book The Blessed Eucharist, Fr. Michael Muller mentions the incident of a man who desecrated the Blessed Sacrament during the burning of the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown, Massachusetts, in 1834. Triggered by his very brief description of that sacrilege and how God’s hand swiftly struck down against the guilty one, I went to look for further data. Here is a more detailed presentation of what occurred on the hot summer evening of August 11 in that Puritan town, today annexed to Boston.

An intense anti-Catholic environment

While many people realize that our country’s colonial period was vehemently anti-Catholic before the American Revolution, they often imagine that religious tolerance of Catholicism magically appeared after the First Amendment was ratified in 1791 (“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof”…). Although this amendment granted freedom of religion to all American citizens and began the eventual repeal of anti-Catholic laws from statute books in the States, the deep roots of a virulent anti-Catholicism were not so easily deracinated.

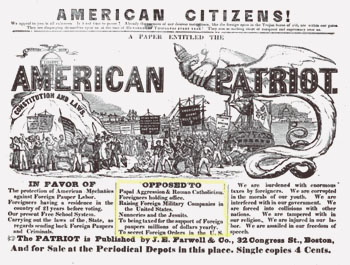

Above, the anti-Catholic American Patriot - hatred for the Pope, the Jesuits and nuns; below, a Protestant cartoon showing fear of the growing influence of Catholic schools

| |

Open manifestations of hatred for Catholics reached new peaks in the early 19th century when Protestants became alarmed at the heavy influx of Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany into America.

In 1790, there were only 30,000 Catholics counted in the entire country, but 40 years later that number had grown to 600,000. In the 1840s, with another great wave of Irish immigrants, the number of Catholics in America had soared to 1.75 million, and, amid the many fragmented sects of Protestantism, Catholicism had become the largest single religion in the country.

The predominantly Episcopalian and Puritan Protestants, who viewed the Catholic Church as the Whore of Babylon, feared and distrusted the growing presence of this new Catholic labor force and its flourishing institutions on American soil. In the 1830s and 1840s, prominent Protestant leaders organized into the Nativist movement and attacked the Catholic Church as not only theological unsound but an enemy of republican values. There was even a movement led by Lyman Beecher to exclude Catholics from new settlements in the West.

These decades saw incidents of mob violence against Catholics, the burning of their properties, and even outright murders. An early episode of such aggression was the burning of the Ursuline Convent in Charlestown, showing us how intense that popular sentiment against Catholicism was.

An unruly mob storms the Ursuline Convent

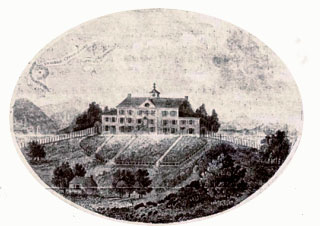

In August of 1834, resentment and hatred had risen to a high pitch in Charlestown, a town on the outskirts of Boston, against the growing Irish Catholic population. The odium found a target in the prospering Ursuline Convent and its teaching Academy founded in 1826 on a 24-acre enclosed property on Mount Benedict, a hill overlooking Boston Harbor.

The Ursuline Convent on Mount Benedict | |

Many prominent Protestant families had enrolled their daughters in the Ursuline Academy to receive a European-style education. Naturally, conversions followed, such as Episcopalian Rebecca Reed, who was enrolled as a day student and then became a postulant in 1832. To the Protestant farmers and workers of Charlestown, with their deep Puritan roots, it looked like these girls were being corrupted by Rome.

Six months into her novitiate, Miss Reed left, angry that the Mother Superior had judged her an unstable candidate and refused to allow her to take her first vows. Encouraged by the Episcopalian minister William Croswell she wrote a dramatic account of the supposedly macabre practices and dictatorial rule in the Convent. This self-dramatized piece on her exit from the Convent was published, largely spread, and stirred to high pitch anti-Catholic sentiments against the Ursuline establishment.

Then, two weeks before the riot, Sister Saint John, assistant to the Mother Superior, left the Convent in the middle of the night. This Sister, who was suffering from a nervous condition, returned of her own will the next day. Rumors began to fly, however, that her return had been forced. Local papers published stories about a “mysterious woman” being kept against her will in the Ursuline Convent, and signs were posted calling for the workmen of Boston to “demolish the Nunnery.”

Local officials visited Sister St. John in the Convent and issued a statement reporting her in good health and free to leave if she wished. Despite these facts, anti-Catholic sentiment among the Protestant populace seethed.

On the evening of August 11, 1834, an unruly, drunken mob – some with faces painted like Indians - gathered at the Convent gates. Using foul language, they confronted the Mother Superior, demanding the release of the “mysterious woman” supposedly being held against her will. When she boldly refused, they tore down the gate and entered to wreak havoc.

They broke the windows, destroyed the furniture and musical instruments, and built a large bonfire, feeding it with the church Crucifix, altar ornaments and books from the Convent library as a crowd of 4,000 looked on. Charlestown’s Protestant firemen, who had been called early to the scene, stood idly by or returned to their stations.

The Holy Eucharist is desecrated

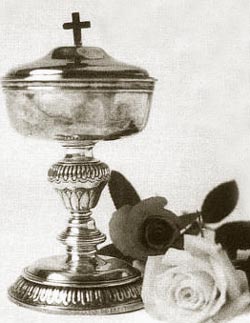

The silver ciborium only returned to the Ursulines a century later | |

When the mob started to tear down the front gate, Mother O’Keefe of Saint Joseph and Sister Saint Ursula rushed to the Chapel to remove the Tabernacle, which housed a ciborium containing consecrated Hosts. They hid it in a rose bush in the Convent garden, thinking it could be retrieved after the rabble left. Then they joined the other sisters and girls, who had gathered in the garden and were fleeing through a hole they had ripped in the wall to escape and find shelter and safety at a neighboring farmstead.

Outside the burning Convent, a rough laborer from Newburyport named Henry Creesy and several others had found the Tabernacle from the Chapel’s altar in the rose garden. Inside was a silver ciborium containing consecrated Hosts. Laughing and tossing the chalice aside, Creesy placed three of the Hosts in his breast pocket. He looked up and saw flames coming from the Convent window. Shrieking with laughter, he mockingly exclaimed, “Now I have God’s body in my pocket.”

By one-thirty a.m., the whole building was engulfed in flames. The uncontrollable mob was not finished. They went to the garden mausoleum under the pretense of releasing imprisoned sisters. They found only the graves of six or seven sisters, which they proceeded to desecrate, prying the tops off the coffins and throwing the bones onto the floor. Then they set fire to the remaining buildings on the grounds, the barn, the stables, an icehouse and a restored farmhouse. By daybreak, the Ursuline Convent on St. Benedict Hill was a heap of smoldering ruins.

Not satisfied with this outrage against the Catholics, they returned the following night and tore up the garden beds and destroyed the orchards.

Continued

Posted January 28, 2011

Related Topics of Interest

Catholicism in Colonial America Catholicism in Colonial America

La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna

The First Thanksgivings Were Catholic The First Thanksgivings Were Catholic

Pilgrims and Puritans Pilgrims and Puritans

Pasquala of Mission Santa Inez Pasquala of Mission Santa Inez

Testimonies of Mary of Agreda's Presence in the U.S. Testimonies of Mary of Agreda's Presence in the U.S.

The Rainbow Crossing Miracle The Rainbow Crossing Miracle

Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus: Apostle of New Spain & Texas Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus: Apostle of New Spain & Texas

Related Works of Interest

|

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|