|

American History

The Appeal of the Stones

at San Juan Capistrano

Hugh O'Reilly

Mission San Juan Capistrano, "The Jewel of the California Missions"

|

In 1769, when the American Revolution was in gestation, setting a first experiment for what would be the Modern World, a humble Spanish Friar was crossing the borders between Baja and Alta California, and founding the first Franciscan mission in what would be the most prosperous State of the future United States of America.

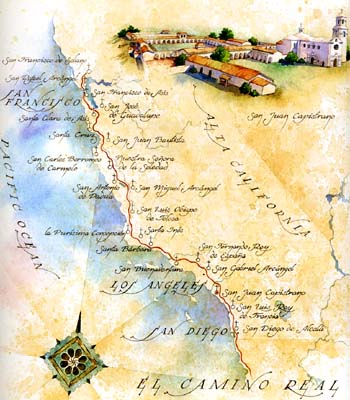

After the first California mission - San Diego of Alcalá - had been established, Fr. Junipero Serra continued traveling north setting up many others. The Mission of St. Juan Capistrano was founded on November 1, 1776, All Saint’s Day, just three months after our Country declared its independence from England.

Arizona Department of Transportation |

The efforts of Fr. Serra did not end there. He continued to walk north and many other missions issued from his saintly, tireless work. The present day city of Los Angeles would rise from the Mission of St. Gabriel. Also the missions of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, San Francisco and San Jose, to mention only those that gave origin to important cities, were founded in the same period. Among the 26 California Franciscan missions, which constituted a splendid chain along the South Pacific coast, San Juan Capistrano is considered the best conserved, which is why it is called the Jewel of the Missions.

The story of the California missions was thus added to the early Catholic History of our Country. Even before that time, numerous missions had been established from the early 1600s on in New Mexico by the Jesuits, with Blessed Eusebio Kino one of their most famous leaders. A half century before Fr. Serra began his epic work in California, Ven. Antonio Margil was making an analogous initiative in Texas [click here].

Appeals of Divine Providence that were not heard

Knowing these first Catholic missionaries in our land can help us to understand what Divine Providence was planning to give to our newly born Country in order to protect it from the bad influences that had already been established in it. For various reasons, these Catholic seeds did not germinate in California.

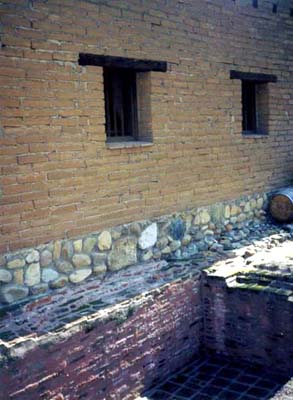

The wine-press of St. Juan Capistrano where the first California wine was made |

At first, the missions thrived and prospered, spiritually and materially. Many Indians converted and lived in the missions, receiving religious and cultural formation as well as an efficient professional instruction. To speak only of the latter, the missionary effort allowed the Indians to learn systematic methods of farming and livestock production. When you visit San Juan Capistrano, for example, you can still admire the well-organized site where the Indians crushed grapes under the supervision of the missionaries. That was, in fact, the first wine made in California. The Indians also learned to write, read, carve, paint, and sing following the good schools of the time, brought from Spain by the missionaries.

Resentment of this progress and wealth grew among the enemies of the Church, and in 1821, when Mexico declared its independence from Spain, its anti-clerical government claimed Alta California and began the secularization of the missions, expelling from them the Franciscans.

In 1848, Mexico lost a war against the United States and had to cede Alta California. Shortly before that, gold was discovered in Sacramento Valley.

Soon thousands of gold-diggers would descend from all over the Union to California in quest of a quick fortune. Often, those men viewed the Indians as enemies and contenders for rights and land, and mutual fighting began. The missions fell into ruins. Mission San Juan Capistrano was sold in 1833; the others suffered a similar fate.

When the State of California came into the Union in 1867, there was great interest in the newfound wealth of the territory, but unfortunately no concern to know the plan of Divine Providence for this land. This is one reason why our State and Country continue to be primordially money and pleasure-oriented.

If Catholics would have nurtured those first seeds and been faithful to that call to establish a Catholic civilization, organically integrating the neophyte Catholic Indians into the population, what might have taken place? The early heroic Franciscan examples of dedication for the cause of Christ were there to be followed. Alas, this did not happen ...

But God does not change His promises. The echo of that appeal - even though it no longer finds resonance in the hearts of most modern men - can still be heard in the stones of the Mission calling us to a return.

The vestiges ask for a Catholic restoration

A material restoration of San Juan Capistrano Mission began in the early 1900s. Fr. John O’Sullivan, who arrived in 1910, restored Serra Chapel, installed the Golden Altar, built a mission school, planted gardens, and installed the fountains that still splash today. Further, the stories he wrote - e.g., about how the swallows would return to San Juan Capistrano each year on St. Joseph's feast day - showed how the spirit of the old grace of the Mission remained alive with its historic charm.

In his book Capistrano Nights, Fr. O’Sullivan reported how the Faith planted by the Franciscans endured in the people of the Mission, as seen, for example, in the story of Polania Montañez. She taught religion to the town’s children before Fr. O’Sullivan arrived. When the town was suffering from a severe drought in the 1890s, she organized the children into a procession carrying a Crucifix and statue of St. Vincent. They set out for the ocean front, praying to God all the while to send rain. When they reached their destination, the heavens opened with such force that wagons from town were sent to bring back the faithful and jubilant group.

With the goal of spreading this echo of the Catholic past of California and showing the marvel of these missions, I begin to explore this grand chain of California missions by making some modest comments on pictures taken during a visit to Mission San Juan Capistrano.

The Mission stands in the valley opening to the sea and backed by a half circle of gently swelling hills, flecked with bright colors of wild flowers. The people used to say that the Virgin Mary had been walking in the hills, and the wild flowers sprung up where her feet touched the ground.

In this spirit, I invite you to view this mission of times past.

A walk in the gardens of Mission San Juan Capistrano

When you enter the gates of the San Juan Capistrano Mission you leave behind you the world with its agitation, self-interest, and concern for pleasures. You enter a past of peace, recollection, and seriousness. The rustic and beautiful colonial Spanish arches of the buildings provide shade and a light breeze for your body, and a spirit of well-being for your soul.

At the entrance patio, you come upon an old cannon, above left, reminding you that in its first years the Mission and its inhabitants were protected by a 10-soldier garrison from enemies coming from the sea as well as other hostile Indian tribes. The presence of the Spanish soldiers provided a relative security for the missionaries, who catechized the Indians and taught them new skills, directed the building projects, and oversaw the workshops, gardens, and livestock.

The cannon sits in front of the soldier quarters, above right. A building that does not lack charm and beauty in its simple, rugged lines.

Through the open doors, above left, you see the courtyard and central garden, the very heart of the Mission's life. The courtyard was also a place of prayer and meditation for the friars, where, turning their spirits to Heaven, they rested from the hard work of the day.

In the center of the cloister garden is a large stone fountain, above right. Along with the shade of the large trees, it refreshes the air. The continuous trickling of water falling from the fountain to the grand brick basin creates a sweet, joyful melody that calms your spirit and fills it with peace.

The atmosphere of the cloister is grandiose and serene. Above, the austere and elegant campanario [bell tower] supports the small bell that regulated the internal life of the Mission, calling the friars to the Divine Office, meals, or practical works.

The building above that houses the Chapel, gives the impression of strength, like a small fortified castle. In it the only original mission church still standing in which Fr. Serra is known to have celebrated Mass.

At a corner of the courtyard, a series of arcades provides access to the Chapel. The richness and subtlety of the play of lights and shadows is remarkable. Although these buildings were designed to achieve various practical purposes, because they were constructed in an era of robust Faith, they make a delightful impression on your eyes, emanating a serenity that permeates your very being.

You cannot miss visiting the side altar dedicated to St. Peregrine, above right, patron saint for those with cancer. The heat from hundreds of candles placed there by the faithful fills the small room and makes it 10 to 20 degrees warmer than the Chapel. When you enter the Chapel you are in a haven of silence and piety, with some faithful praying quietly on the wooden kneelers.

The Chapel delights you with its Spanish colonial simplicity and, at the same time, grandeur. Your eyes are directed toward the monarchical point of the building, the Tabernacle and in it the Holy Eucharist. There you are invited to think about and admire the other mysteries of our Holy Faith, which spark in your soul a desire for Heaven. An artist could spend hours gazing at the details of the beautiful old Golden Altar that dominates the Chapel.

The entrance to the cemetery, next to the Chapel, is marked by a stone cross, above left, that pays homage to those who built the Mission and were buried there. Many persons, including friars, Indians, and families of parishioners are buried in unmarked graves in its silent confines. In that gravel pasture of peace, you feel the blessing of lives offered to serve God and expand His Reign on earth.

Leaving the cemetery, you see the four bells, above right, that once rang from the bell tower of the Grand Church, which today stands in ruins. The two larger bells are called San Vicente and San Juan. The two smaller, San Antonio and San Rafael. They are inscribed with dedications to Our Lady. These bells would ring to call people to Mass and to mark the morning, noon, and evening Angelus.

They also announced the deaths of parishioners. Fr. O’Sullivan tells the story of Matilda, a young Indian girl in the 1850s who used to help in the sacristy, washing and ironing altar linens. She was a very good girl but some jealous persons spoke evil of her. When she became ill and died unexpectedly, these Mission bells sounded of their own accord miraculously, giving witness to her goodness and rebuking those who had slandered her. And after that, nobody ever said a word against her.

As the tour winds to its end, you find the ruins of the Church, above. Begun in 1797, it took nine years to complete, constructed by the dedicated labor of the missionaries assisted by the Indians. This seven-domed Church was the largest man-made structure west of the Mississippi.

Six years after its completion, on December 8, 1812, a massive earthquake struck during morning Mass. The walls crumbled and the dome caved in, killing 42 worshippers. The church was never rebuilt.

What happened? There is a popular tradition that says the Mexican architect who designed the Church was of the Aztec religion and carved pagan symbols into various parts of the Church. This would have raised the wrath of God, Who destroyed the building.

If this wasn't the reason for such a disaster, could it be a chastisement for some other hidden sin? Or perhaps God was asking the sacrifice of those lives to preserve the Catholic Faith in California. Who knows? It is a mystery that adds to the attraction of the Mission.

Walking in the peaceful gardens, resting on a bench in the shaded courtyard or contemplating the ruins and buildings of Mission San Juan Capistrano, the rich blessing of the past gives you hope and invites you to dream of a Catholic future for the United States that will fulfill the promises of God that, in many ways, one still senses in this blessed place.

As you end your visit in the Mission, you come upon the statue of Fr. Junipero Serra, above, teaching the way of Heaven to an Indian boy.

It reflects well the primary aim of those saintly men who came to our Country to expand the Kingdom of Our Lord Jesus Christ and lead souls to salvation. Without their dedication, the Mission buildings would never have existed. This is why, still today, within these Mission walls you feel a strong Catholic spirit and a call that emanates from those sacred stones inviting us to return to the plans of God for us and for our Country.

Posted July 12, 2006

Related Topics of Interest

La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna La Conquistadora: Our Country's Oldest Madonna

Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus: Apostle of New Spain and Texas Ven. Antonio Margil of Jesus: Apostle of New Spain and Texas

Refuting the False Statements about Life in the Middle Ages Refuting the False Statements about Life in the Middle Ages

Heroes of the Church and the North American Indians Heroes of the Church and the North American Indians

St. Philippine Duchesne: Failures became her success St. Philippine Duchesne: Failures became her success

|

History | Home | Books

| CDs | Search

| Contact Us | Donate

© 2002-

Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|