|

World History

Medieval Famines, Bread & Wine

Hugh O’Reilly

It is commonly held that the Middle Ages was one long period of constant hunger and famine. To negate this falsehood, historian Regine Pernoud points that until the end of the Middle Ages famine was conceived differently. It was not the total absence of food, as we consider it today, but the lack of wheat or corn bread. Thus, when the people of a certain area were instead eating rye bread, they would say that they suffered famine. Even then, those famines were generally localized and of short duration.

From the description of the basic table fare – bread and wine – presented below, one can see that the life of the great and small in the Middle Ages was good, certainly not the picture portrayed by modern revolutionary propaganda.

A legend that dies hard has made of the common man in the Middle Ages an everlasting starveling, so that one wonders how a race that was supposedly under-nourished for eight centuries and which was, besides, ravaged periodically by wars, famines and epidemics, ever managed to survive and, in addition, to produce passably vigorous descendants.

The error arose largely from a misinterpretation of terms then in use. It is true that in France in the Middle Ages men ate herbes and racine - (herbs and roots). But that has always been the case, for at that time herbe meant anything that grew above the soil - cabbage, spinach, lettuce, leeks, beets, etc., and racine meant everything that grew below: carrots, turnips, radishes, etc.

Peasants working in their fields |

The peasant often collected acorns, but it was not because he liked them himself, but because he fed his pigs on them. It is possible that during certain periods of exceptional distress - for instance at the time of the Anglo-French wars that marked the end of the Middle Ages when the horrors of plague were added to those of war and when mercenaries ravaged a country whose defenses were no longer organized - acorn flour may have served as a substitute. But no documents permit one to suppose that this happened frequently.

It is also an error to imagine that famine was endemic in the Middle Ages. Certainly there were famines in the Middle Ages and these were numerous. Such occur inevitably at any time when the absence or insufficiency of means of transport prevents help from being brought swiftly to threatened regions and hinders the exchange of produce. But it is certain also that these famines were very localized and did not usually extend beyond the area of a province or a parish.

One must, moreover, be quite clear as to what one understands by famine. A document quoted by Luchaire, in a work where he deliberately accumulates texts liable to show the period in the most gloomy light, is calculated to leave present-day readers perplexed. “This year (1197),” relates the Chronicler of Liège, “the corn harvest failed. From Epiphany to August we were obliged to spend more than 100 marcs on buying bread. We had neither wine nor beer. A fortnight before the harvest we were eating rye bread.” If famine consisted for them in having to eat rye bread, how many people in recent years would have envied the lot of their 13th century ancestors!

In fact, medieval food was not very different from our own in normal times. Its basis, naturally, was bread, which was made, according to the richness of the district, from wheat, rye or from a mixed crop of both these. But it is to be noted that even in non-productive districts such as the South of France, people ate wheat bread. In Marseilles, where the land was poor in corn and where exceptional measures had often to be taken for the city to get its supplies, there was no mention of lower-grade flours in the very detailed regulations governing bread-making.

Baking white bread in an Italian city |

Three sorts of bread were made: white, mejan, which was coarser, and whole meal. The prices were fixed according to a strict tariff drawn up by three master-bakers assisted by a responsible man appointed by the guild. Many varieties of fancy bread were known in Paris, of which pain de Chilly and pain de Gonesse or rolls, were the most highly esteemed. In very poor districts, people ate oatcakes, which are still popular among the Scots, or buckwheat.

But no district was completely without bread because the agricultural system of that time, based on large estates covering a relatively extensive area, favored the planting of many different kinds of grains and vegetables. In the Middle Ages one never saw one region turned exclusively to the raising of corn or the growing of vines, and importing the rest of the produce it needed. The system of vast cultivated estates allowed a sufficient variety of crops and, at the same time, a proper proportion of land for each. The illuminated manuscripts that drew their inspiration from reality are very revealing on this subject. Everywhere one sees a constant proportion of meadows to fields and fields to vineyards.

The vine was cultivated everywhere in France. Some present-day wines were highly esteemed at this time: Beaune, Saint-Emilion, Chablis and Epernay; others are no longer as famous now as they used to be, for example, Auxerre or Mantes-sur-Seine. Everywhere local produce had to be protected from imported products, and, in a city such as Marseilles, draconian measures were taken against the introduction of wines or grapes from other regions.

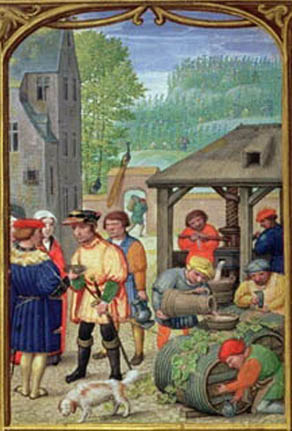

Preparing for the October wine harvest |

In Marseilles, for example, it was forbidden to offer other local wine for sale before the Marseilles merchants had sold their own. The cultivation of the vine was more highly developed in Marseilles then than now and the city by-laws afforded local produce special protection: Hunting in vineyards was forbidden, except to the owner; and the métayer [renter farmer] was not allowed to pick more than five bunches of grapes each day for his personal consumption.

Wine was, in effect, the principal drink in the Middle Ages; beer was also drunk, chiefly barley-beer, which the Franks and Germans had made previously, and also mead. But wine was preferred above all and was found on every table from that of the lord to that of the servants. It was drunk both for pleasure and as a medicine; all sorts of strengthening properties were ascribed to it and it was included in a host of elixirs and pharmaceutical products, jellies and syrups.

People were also very fond of various sweet wines and hippocras, a type of cordial in which aromatic herbs, such as wormwood, hyssop, rosemary and myrtle, were macerated, with sugar and honey added. Before going to bed, people generally drank a boiling concoction of wine and curdled milk, which was called a posset in England and Normandy.

It does not appear that there was any reason for fearing the evils of alcoholism and the degeneration that is common in our days. Doubtless this was because no chemicals and no adulterated by-products were served as drinks; or possibly because general observation of the precepts of the Church allowed its use but checked its abuse.

At any rate, wine was common, on the tables of the great lords as well as peasants, and even served regularly in the monasteries and convents.

Based on Regine Pernoud, The Glory of the Medieval World

London: Dennis Dobson, n.d.,

Posted November 9, 2011

Related Topics of Interest

Work and Leisure in the Middle Ages Work and Leisure in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages - A World of Brilliant Colors The Middle Ages - A World of Brilliant Colors

Refuting Myths of the Middle Ages Refuting Myths of the Middle Ages

Women in the Middle Ages Women in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages, a Forest Filled with Symbols The Middle Ages, a Forest Filled with Symbols

Hernan Perez del Pulgar of the Valiant Deeds Hernan Perez del Pulgar of the Valiant Deeds

The Three Orders of Medieval Society The Three Orders of Medieval Society

Related Works of Interest

|

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|