|

World History

The Great Adventure of the Templars

Hugh O’Reilly

What catches our attention is the adventure undertaken by the Templars for two centuries over lands and souls. It is the audacious title of monk-warriors that they bore in that still brutal and cruel world.

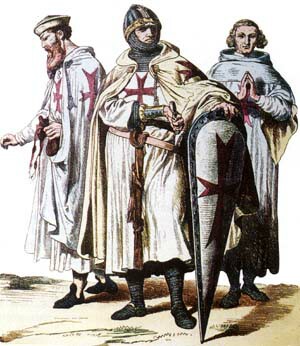

When we imagine them with their short hair and long beards, their white mantles with the scarlet crosses floating on their shoulders like angel wings, dashing on their small Arabian horses from battle to battle, and being cut down – one after another – under the blows of swords, their memory lets us dream. For we know that their mission had only one goal that excluded every human interest: their eternal salvation and the honor of Christendom.

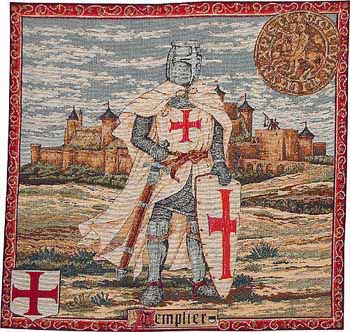

The Knights Templar |

The Order of the Temple was born in Jerusalem in 1118, fruit of the desire of a pious knight from Champagne, Hugues de Payens, to help and protect the pilgrims who came from all of Christendom to the Sepulcher of Christ. Even after the First Crusade, the road was not easy for these travelers to the Holy Places. They were continuously attacked, beaten, extorted, enslaved or killed by the Turks.

Seduced by the shimmering sand and the calm Mediterranean waters, the crusaders who stayed in the Eastern Frankish Kingdom established colonies that had to be protected. Since its troops were insufficient, they required more armed protection. To fill this need, Hugues de Payens gathered together his relative Godfrey de Saint-Omer and others related by marriage or blood – they were just nine at the beginning – under the title The Poor Knights of Christ.

The Order was officially endorsed by the Church at the First Council of Troyes in 1128, where the Poor Knights of Christ received their charter of chivalry from St. Bernard in the presence of a Pontifical Legate, two Archbishops and ten Bishops. The new King of Jerusalem, Baldouin II, hosted them in his palace, near Solomon’s Temple, whence came their name.

With their orders they also received a Rule whereby they committed to observe poverty, obedience and chastity. Yes, also chastity: without it the Order of the Temple would not have existed. “Chastity is the security of courage,” the Rule reads.

I quote only one of its most beautiful texts, which embodies the spirit of the whole Order, the renunciation it demanded, and the grandeur it gave in exchange. On the day the knights asked to be received into the Order, they would go to the Temple and its doors would open before them. The Master would call out:

“Do you renounce your own wills and the service of the King for the salvation of your souls and to pray according to the rules and customs of the recognized Masters of the Holy City of Jerusalem? In exchange, God will be yours insofar as you promise to abandon the deceitful world for love of Him and to despise all the torments of your hearts. Nourished on divine food, inebriated by the Commandments of the Lord, we fear not to enter battle, for this is to walk toward our crowns.”

The First Crusade cost too much blood and gold for its fruits to be scattered. To support the Templars – monks but also soldiers – was to sustain the effort of Christendom in the Holy Land in a climate of general religious enthusiasm. This explains the extraordinary growth of the Order after the Council of Troyes.

Following the Pope’s command that the envoys of the Temple be warmly received, Toulouse opened its doors to a Templar delegate, and donations of money and goods as well as vocations flew to the Order. The Pope confirmed its mission “of combating the enemies of the Cross,” and, to reward it, he placed all the houses and goods of the Order under papal protection, making them exempt from all authority except that of the Pope. He also freed them from paying any taxes.

Its internal life

Those early Templars were of a powerful and fierce temper: they were difficult to kill. They did not travel to the Holy Land to have a contemplative life, but to wage war - that is, to fight with the sword, to charge into battle and accomplish difficult feats. “We came and we resist by the force of our arms,” was a motto.

A life of submission to a high cause |

For them the battle was their daily bread, as necessary as prayer. Their standard was white and black as a sign that Templars should be frank and good with their friends, but black and terrible with their enemies.

At night they would rise to recite Matins; afterward they would inspect their horses and equipment to be sure they were ready for battle. They rested again until the bell rang for Prime. Then they would rise, attend Mass, and work until noon, when they would take their first meal.

In the afternoon they would recite None and Vespers; the bell would ring yet another time for Compline. At its end, the Templars would assist at a ceremony where they would receive their orders for the next day. Each one would again inspect his mount and equipment, and, finally, in that great monastic silence, they would say their prayers and retire.

We can easily imagine that those men leaving the Chapel to care for their horses and repair their weapons, prepared to jump into the saddle and enter combat, were not boys. Nonetheless, their statutes curbed their brutality and inculcated sweetness in their relations with their brothers, and amenity to a ready subordination and courtesy.

Their mission

Their mission and their privileges did not make their lives easier. The Templar was not at the service of the King’s politics; instead he influenced the King to follow the Order’s politics which aimed to increase Christian prestige in that Islam land. The Templar respected the Bishops, but his first allegiance and obedience was to the Pope.

Jacques de Molay, the last Templar Grand Master |

During one difficult period, the Temple went a year and a half without a Great Master. The Order suffered much from bloodshed and humiliations. But its misfortune and its courage in trial ended by moving Europe. Indeed, the men who escaped that period of great trial still had the audacity of make the Siege of Acre. For this reason, a new Crusade would be launched two years later.

In a disastrous campaign of 1187 they went to the assistance of Tiberias, under siege by Saladin. They formed the rearguard of the army of Guy de Lusignan, “the most beautiful army seen in the Holy Land,” the historians say. A monumental tactical error, however, exposed them to attacks of the Saracens, who surrounded them and cut them off from the water supply. After days of combat – engraved in the memories of the few who survived – the army was completely destroyed.

The Sultan delivered the Templars to the Mohammedan religious sects that tortured them before beheading them. They were told their lives would be spared if they would embrace the religion of Islam. Of the 230 Templars, none apostatized.

Spiritual adventure

These were the men who were calumniated by most of the Princes who traveled to the East because they would not serve their interests. How could the Templars attach themselves to the Princes of the world when their sights were turned first and foremost to the highest goals of Christendom? They strove to gradually free themselves of every human interest to accomplish their dream – perhaps also that of the Papacy – of becoming the Holy Army of God among men.

If they were not there, the Kingdom of Jerusalem would have lasted two years instead of two centuries. Suffering defeats and gaining victories, they fueled the sacred fire. Without the war they waged, there would have been no second, much less a third Crusade.

The Templars are indeed curious personages. Their grandeur would not have endured if it were based on pride. In fact it was founded on sacrifice.

The Templar understood that it was easier to win a battle than to conquer himself. Perhaps it was this, more than anything else, that made the Knights Templar the most qualified representatives of Christendom, inspiring respect even among the Infidels. The Sultans were more apt to address the Masters of the Temple than the Kings. Adding sanctity to courage, they were truly the flower of French Chivalry.

A body and soul of iron |

These attributes generated a unique personality, rough but at the same time generous and charming. To this is added the mysteries of the chapter meetings, which were attended only by the members of the Order.

A man would not ask to enter the Temple’s ranks to enjoy personal triumph. If such illusion of glory led him to its door, it would vanish after his talk with the Master who would clearly present the aims of the Order.

“Brother,” the Master would tell him, “you are asking for something grand, for in our Order you see nothing but the outer shell. You see us with beautiful horses, arms and clothing; you see us eating and drinking well, and thus you think that all is easy.

“But you do not know the strong orders that are inside. For it is a great thing that you, who are the master of yourself, will become the servant of another. You will never do your own will: If you want to be in Acre, you will be sent to Tripoli, Antioquia, Armenia, Puglia, Sicily, Lombardy, France or England, or any other place where we have houses and lands. If you want to sleep, we will make you keep vigil; if you want to keep vigil, we will send you to sleep in your bed…”

“Brother, you should not seek our Order if you are looking for riches, honors or lordships, or for the comfort of your body. But you should seek it for three things: first, to avoid sin; second, to serve Our Lord; and third, to live poor and make penance in order to safeguard your soul.

“Now, consider well, dear brother, whether you can bear these hardships.”

Then, if the candidate agreed to these terms, he would listen to the reading of the Rule and pronounce his vows.

Was this the language of a small cause? To enlist in it, did one not need to have a soul and body of iron? “The road of God is not comfortable,” the Rule reads.

It seems to me, however, that what definitively summarizes its spirit is its motto: “The most beautiful adventure in the world is ours.” Yes, the most beautiful adventure of heroism and sanctity, for until the end one was not permitted to stop on that road without risking the loss of everything: his honor and his soul.

Based upon and translated from Jules Roy, Historia, n. 139

Posted April 9, 2010

Related Topics of Interest

St. Bernard's Letter Addressed to the Templars St. Bernard's Letter Addressed to the Templars

The Prayers of a Knight The Prayers of a Knight

St. Bernard of Clairvaux St. Bernard of Clairvaux

The Da Vinci Code: Blasphemous Thesis and Bad History The Da Vinci Code: Blasphemous Thesis and Bad History

Departure for the First Crusade Departure for the First Crusade

Hernan Perez del Pulgar of the Valiant Deeds Hernan Perez del Pulgar of the Valiant Deeds

Understanding the First Crusade Understanding the First Crusade

Related Works of Interest

|

|

History | Home | Books | CDs | Search | Contact Us | Donate

© 2002- Tradition in Action, Inc. All Rights Reserved

|

|

|